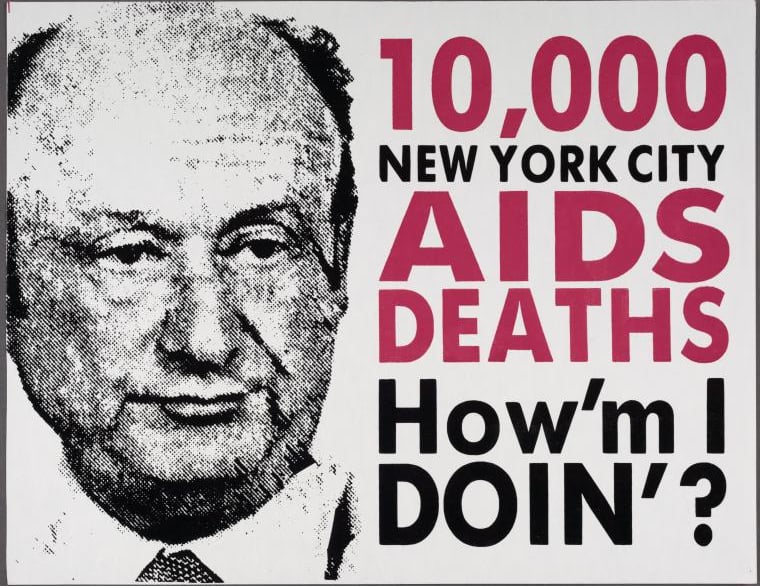

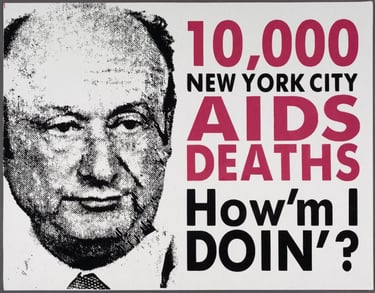

Sacred Ground, Living Memory: The NYC AIDS Memorial

Studio a+i. New York City AIDS Memorial at St Vincent’s Park, NYC. Photo courtesy of the New York City AIDS Memorial website.

AIDS had been part of New York’s story since 1981, yet it was not until thirty-five years later, long after the Gay Liberation Monument was placed in Christopher Park in 1992, that the city unveiled its first purpose-built AIDS memorial. The long delay was not simply the result of bureaucracy but of a deeper cultural reluctance to confront queer suffering, especially the compounded losses at the intersections of race, class, and sexuality. That the New York City AIDS Memorial finally emerged was due not to state initiative, but to the persistence of activists, preservationists, and community members who refused to be erased.

Unveiled on World AIDS Day in 2016, the memorial stands at St. Vincent’s Triangle, a small park where Greenwich Avenue, Seventh Avenue, and West 12th Street meet in the West Village. Its location is no accident: just across the street stood St. Vincent’s Hospital, home to the first and largest AIDS ward on the East Coast, where thousands of New Yorkers received care and where many took their final breaths. To place the memorial here is to acknowledge not only a public health crisis but also the geography of queer life, grief, and resistance. Its presence is both overdue and profoundly meaningful, a civic acknowledgement of loss, a site of resilience, and a reminder that AIDS memory is inseparable from the very landscape of New York City.

In the foreground, the triangular latticework of the New York City AIDS Memorial. Behind it rises the O’Toole Building, its white stucco façade punctuated by porthole windows and scalloped overhangs—a relic of its origins as the National Maritime Union headquarters. Repurposed during the epidemic as St. Vincent’s Comprehensive HIV Center, the O’Toole’s circles stand in stark contrast to the memorial’s angular steel canopy, a juxtaposition that reflects the layering of history on this site. https://www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/12066-nyc-dedicates-new-aids-memorial-in-greenwich-village

Design, Space, and Meaning

The NYC AIDS Memorial does not resemble a traditional monument. Instead of statues or stone plinths, visitors encounter a soaring canopy of interlocking steel triangles that rises eighteen feet above St. Vincent’s Triangle in the West Village. Designed by Studio a+i, the structure is both delicate and commanding. Its sharp, angular geometry recalls a fractured surface, at once beautiful and unsettling. Light cuts through the lattice, casting shifting shadows that remind us memory is never still. The triangular form echoes the shape of the park itself, while also recalling the pink triangle, once used to persecute gay men during the Holocaust and later reclaimed by LGBTQ activists as a symbol of defiance during the AIDS crisis.¹

Beneath the canopy, the granite circle becomes a ritual ground. Visitors can read, sit, reflect, or gather, transforming a former site of institutional care into a civic space of participatory memory. The design thus links different histories of loss and survival, situating the epidemic within a broader struggle for justice and visibility.¹ Beneath the canopy, the granite circle becomes a ritual ground. Visitors can read, sit, reflect, or gather, transforming a former site of institutional care into a civic space of participatory memory. The design thus links different histories of loss and survival, situating the epidemic within a broader struggle for justice and visibility.¹

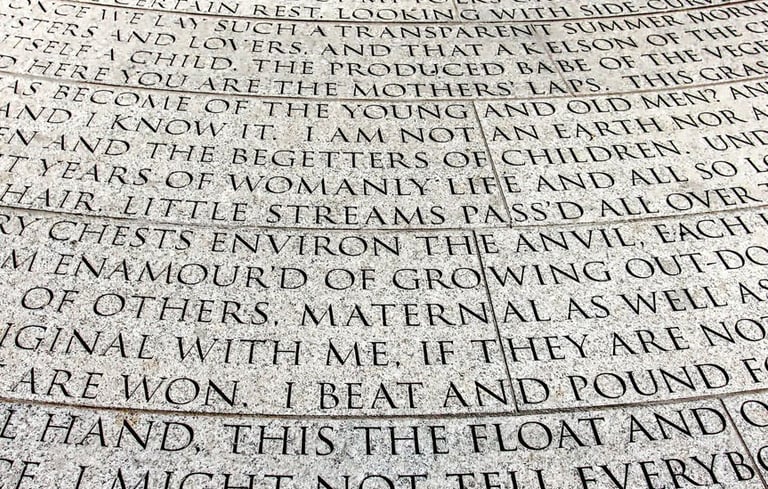

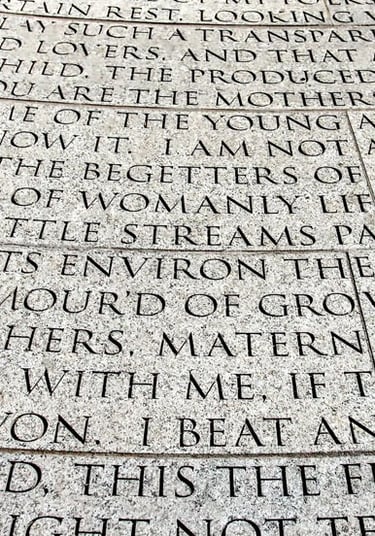

The ground itself is also part of the memorial. Artist Jenny Holzer engraved granite pavers with passages from Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself, one of the most expansive meditations on human interconnectedness in American literature.² Whitman’s words, long read as queer-inflected, invite visitors to reflect on mortality, intimacy, and community, their permanence in stone echoing the resilience of memory itself.. First published in 1855, Whitman’s poem celebrates the body, sexuality, and the shared vitality of life. “Mine is no callous shell,” he insists, affirming the sensitivity of the self; elsewhere, he evokes “the procreant urge of the world,” linking desire to creation itself. Rather than viewing death as a final rupture, Whitman emphasizes continuity, declaring that we are bound together by “the common air that bathes the globe.” To walk across the memorial plaza is to encounter these words underfoot, a reminder that life and death, self and community, remain inseparable.

Unlike more secluded or figurative memorials, the NYC AIDS Memorial stands in the heart of a busy city block. Bike messengers weave past, strollers and office workers share benches beneath the canopy, and the sounds of traffic spill across the park. Its sharp, angular form rises not in quiet isolation but amid the rhythms of daily life, ensuring that grief and resilience remain inseparable from the city’s present. In this sense, it stands apart from other AIDS and LGBTQ memorials in New York: the figurative Gay Liberation Monument in Christopher Park represents Stonewall through sculpture. In contrast, the Hudson River Park memorial offers a contemplative refuge on the waterfront.³ The sharpness and permanence of its steel structure also contrast with the softness of the AIDS Quilt and the transitory power of candlelight vigils or Pride parades, forms of memory that were always fleeting, yet no less vital. Together, they remind us that AIDS memory has taken many shapes: ephemeral acts of mourning and joy, and now a permanent canopy pressed into the fabric of the city.

Yet the memorial also raises questions about aesthetics and accessibility. Its abstraction has been praised for resisting didacticism and critiqued for what some view as its sanitized or overly neutral tone. Unlike the more visceral expressions of grief and rage that marked earlier activist interventions, such as die-ins and political funerals, this memorial is built within the frameworks of contemporary urban development, bordering luxury condominiums and curated green spaces.4

Notes

“NYC AIDS Memorial,” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, accessed December 8, 2024, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/nyc-aids-memorial/.

Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass (Brooklyn, 1855), “Song of Myself.”

“Gay Liberation Monument,” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, accessed December 8, 2024, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/gay-liberation-monument-christopher-park/; Hudson River Park Trust, “AIDS Memorial at Pier 49,” Hudson River Park, accessed September 19, 2025, https://hudsonriverpark.org/the-park/parks-river/aids-memorial/.

Holland Cotter, “Why Can’t New York Make a Proper Monument to Gay History?” The New York Times, June 28, 2024.

What Whitman's Song of Myself as used in Jenny Holzer's AIDS Memorial. Photo by John Moore. Circular Space Photography.

The Layered History of St. Vincent’s Triangle

The wedge-shaped parcel of land now known as St. Vincent’s Triangle reflects the shifting life of Greenwich Village. Bounded by Greenwich Avenue, West 12th Street, and Seventh Avenue, the site first housed the Sheridan Theatre, a 2,342-seat movie palace opened in 1921 during New York’s golden age of cinema.¹ The theater carried cultural weight beyond film: in 1937, Edward Hopper immortalized its interior in his painting The Sheridan Theater, now at the Newark Museum ² and Billie Holiday gave one of her final performances on its stage.³

By the late 1960s, attendance dwindled. On June 17, 1969, the Sheridan closed after showing Ice Station Zebra, starring Rock Hudson. That summer, St. Vincent’s Hospital purchased and demolished the theater, announcing plans for a nurses’ residence. Instead, the lot passed through multiple uses. Neighborhood activists briefly transformed it into a community garden, reflecting the Village’s grassroots culture,⁴ but by the early 1980s, the hospital had erected a utilitarian Materials Handling Center. At this brick facility, linens, food, and supplies were entered through underground tunnels. During the height of the AIDS epidemic, as The New Yorker later observed, those same tunnels discreetly carried out the bodies of patients who had died.⁵

When St. Vincent’s declared bankruptcy and closed in 2010, most of the complex was razed. Only the landmarked O’Toole Building, once the National Maritime Union headquarters, survived as a medical outpost. In its place rose luxury condominiums, echoing the gentrification that steadily displaced queer life from the Village.⁶ Yet the city required that the triangular lot remain a public open space. From this mandate emerged the idea for the New York City AIDS Memorial, dedicated in 2016.

The Geography of Queer Memory

The AIDS Memorial gains significance from its placement at St. Vincent’s Triangle. For decades, the hospital itself had been a place where lovers and chosen families kept vigil, where ACT UP staged confrontational protests, and where thousands with AIDS lived and died. To consecrate this ground as a memorial is to affirm that AIDS history is inseparable from the geography of queer survival.

The surrounding neighborhood amplifies this resonance. The West Village has long been one of the world’s most visible queer enclaves, yet also a site of displacement and policing. Walking to the memorial means passing through a palimpsest of queer history: former bathhouses, activist headquarters, shuttered gay bars, and gentrified streets. Christopher Street anchors this geography, from the Stonewall Inn and Christopher Park to the Hudson River piers, once crowded with men seeking freedom and connection. In the 1980s, those same streets became landscapes of grief, as candlelight vigils, shrines, and political funerals turned sidewalks into sacred ground.² Sheridan Square, at Christopher Street and Seventh Avenue, served as a rallying point across decades: the 1970 Snake Pit raid began there; in 1978, mourners gathered after Harvey Milk’s assassination; in 1979, protests followed the Ramrod shooting that left two dead and six injured; and in 1980, thousands denounced William Friedkin’s film Cruising.³ These events established the square as a geography of defiance long before the AIDS epidemic transformed the neighborhood yet again.

By linking remembrance to these sites, the AIDS Memorial recalls the fragile, fleeting memorials of the crisis years while offering permanence. As historian Douglas Crimp observed, public mourning carried militant force, mobilizing loss into collective defiance.⁸ The memorial anchors those legacies in enduring form.

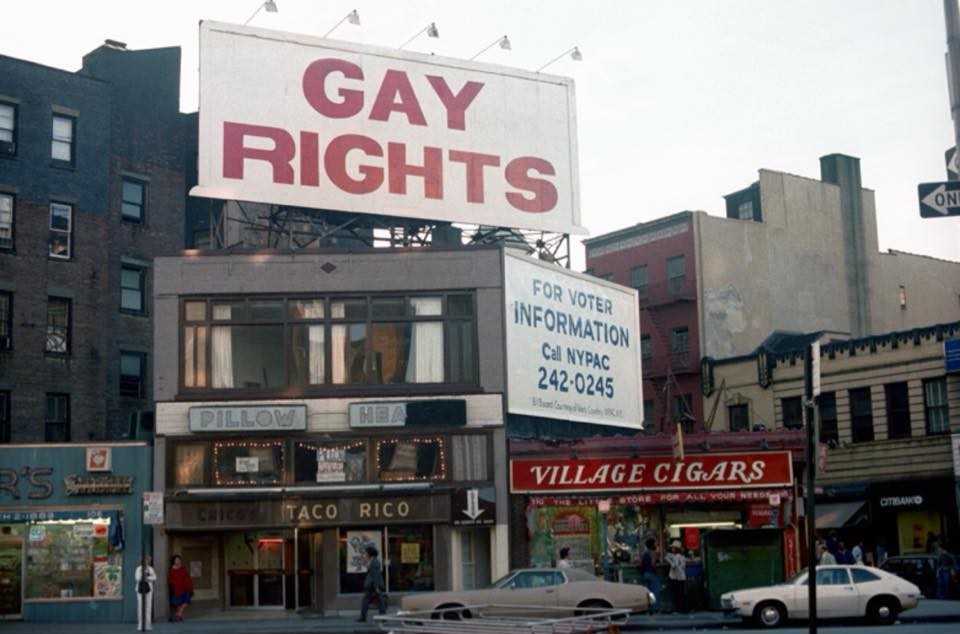

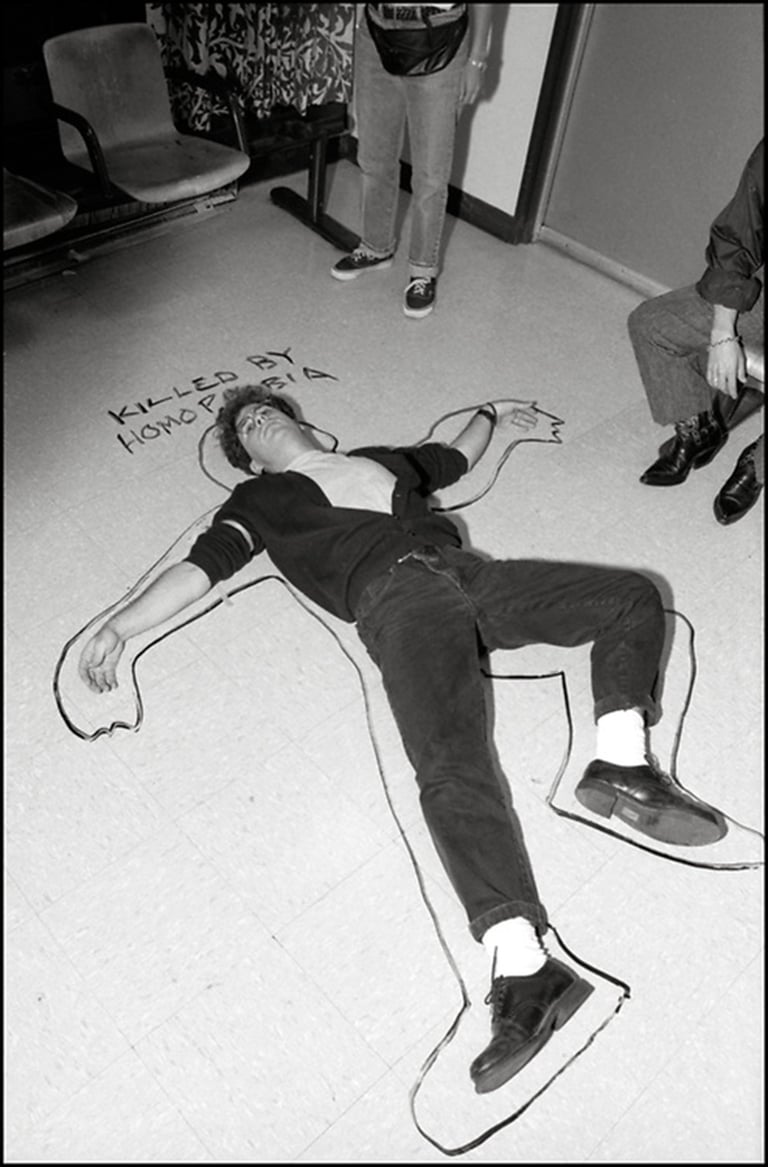

Sheridan Square, 1978. A billboard calling for gay rights loomed over the intersection of Seventh Avenue and Christopher Street, just steps from the Stonewall Inn and Christopher Park. Though not part of the official Stonewall National Monument, Sheridan Square was central to the uprising itself. Crowds spilled into the square during the nights of protest in June 1969, turning it into an extension of the rebellion. At the corner stood Village Cigars—where protesters bought lighter fluid to fight back against police—and the Christopher Street subway station, which David Carter identifies as a key factor in Stonewall’s success, since it allowed queer New Yorkers from across the city to reach the scene and sustain the protests.¹ A bank of phone booths there also enabled people to spread word of the uprising before cell phones. Long a hub of queer protest and visibility, Sheridan Square was later linked to the neighborhood’s AIDS history, with the NYC AIDS Memorial blocks away, further extending this landscape of activism and remembrance. ¹ David Carter, Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004), 163–65.

Preserving Place in a Changing City

The Village’s queer geography has never been static. Rising rents and gentrification have repeatedly displaced bars, clubs, and gathering spaces that once defined the neighborhood.⁹ This makes the AIDS Memorial doubly significant: it resists both the erasure of epidemic memory and the erasure of queer space itself. By consecrating St. Vincent’s Triangle, the memorial ties AIDS remembrance to the very ground where care was given, protests unfolded, and chosen families carried their dead.

Preservation efforts reinforce this point. The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, co-founded by Ken Lustbader, maps and interprets landmarks from hospitals and churches to storefronts, ensuring that queer lives and struggles remain visible.¹⁰ As Lustbader has emphasized, queer memory is inseparable from the places where people actually gathered, resisted, and mourned.¹¹

The National Park Service’s LGBTQ America theme study likewise highlights the historical placelessness endured by LGBTQ communities.¹² This “absence” resonates directly with the AIDS crisis, when traditional institutions, including churches, cemeteries, and archives, often excluded queer grief. Community-built memorials like the one at St. Vincent’s filled this void, carving out visibility when official channels denied it.

As Christina Hanhardt argues, neighborhoods like the West Village are never neutral; they are contested spaces shaped by activism, policing, displacement, and survival.¹³ The AIDS Memorial, situated amid these tensions, insists that memory remain embedded in the geography where queer history unfolded; in the shadow of Stonewall, next to St. Vincent’s, and within walking distance of the piers. It ties remembrance to the city’s streets themselves, ensuring that AIDS memory is not relegated to abstraction but remains part of New York’s living conscience.

Notes

“Sheridan Theater, New York, NY,” Cinema Treasures, accessed September 25, 2025, http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/2084.

Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography (New York: Knopf, 1995), 356.

Stuart Nicholson, Billie Holiday (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1995), 271.

Charles V. Bagli, “St. Vincent’s Hospital Is Closing, Ending an Era,” New York Times, April 7, 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/07/nyregion/07stvincent.html.

Alexandra Schwartz, “New York’s Necessary New AIDS Memorial,” New Yorker, December 2, 2016, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/new-yorks-necessary-new-aids-memorial.

Bagli, “St. Vincent’s Hospital Is Closing.”

Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” in Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 140–42.

David Carter, Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004), 267; New York Times, Nov. 20, 1979.

Christina B. Hanhardt, Safe Space: Gay Neighborhood History and the Politics of Violence (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 10–12.

“About,” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, accessed September 25, 2025, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/about/.

Interview with Ken Lustbader, NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, November 1, 2024.

Megan E. Springate, LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History (Washington, DC: National Park Foundation, 2016), 21–23.

Hanhardt, Safe Space, 10–12.

A plaque at St. Vincent's Triangle commemorates St. Vincent’s Hospital, once the city’s frontline in the AIDS crisis. From the early 1980s until its closure in 2010, St. Vincent’s cared for thousands of people with HIV/AIDS when few other hospitals would.

Sacred Ground: St. Vincent’s Hospital and AIDS Memory

In telling the story of the New York City AIDS Memorial, no site looms larger than St. Vincent’s Hospital. For decades, this Catholic institution in Greenwich Village stood at the intersection of care, crisis, activism, and memory. From its founding in the 1840s during the cholera epidemic to its central role in the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, St. Vincent’s embodied both the compassion and contradictions of the city’s response. Though the hospital has been demolished, its legacy endures through the memorial that now occupies its former grounds, anchoring AIDS memory in the very geography where so much grief and resilience once unfolded.

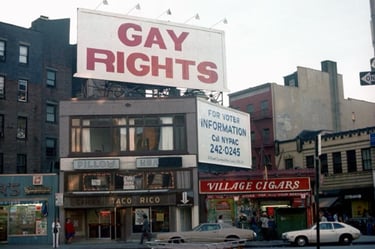

St. Vincent’s was established in 1849 by the Sisters of Charity to treat poor Irish immigrants during the cholera epidemic.¹ From its earliest days, it was known for opening its doors to those whom other hospitals would not treat. That reputation took on new meaning during the AIDS epidemic. In 1984, it opened the first dedicated AIDS ward on the East Coast, becoming what The New York Times later described as “the epicenter of the epidemic in New York.”² At its height, nearly one-third of the hospital’s beds were filled with AIDS patients.³ The strain was overwhelming. Many doctors and nurses feared contact; a 1985 survey found that nearly half of primary care physicians in the U.S. expressed reluctance to treat AIDS patients if given the choice.⁴ And yet, some staff, especially lesbian nurses and volunteers, stepped forward with courage and compassion, ensuring dignity when families and institutions too often abandoned the sick.⁵

Westchester County correctional officers in New York in charge of inmates in the hospital ward wear special garb due to the uncertainty of AIDS. 1983. New York Post Archives

Nursing students treat a patient in the AIDS ward of Saint Vincent's Hospital in the 1980s. Volunteers from the Lesbian community also had the compassion and courage to care for AIDS patients in their greatest hours of need and unimaginable fear. Photo courtesy of Sisters of Charity of New York.

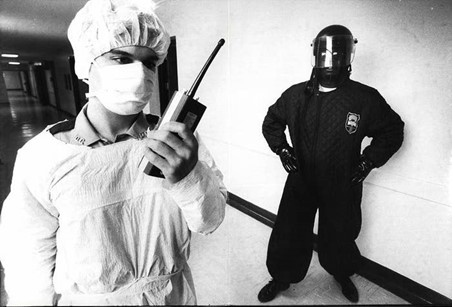

However, St. Vincent’s was not only a site of care, but also a site of protest. On a Monday night in September 1989, ACT UP members learned that a gay man had been ejected from the ER by a security guard for kissing his partner. The story ignited the room. In an instant, the weekly meeting adjourned, and the crowd marched around the corner, taking over the emergency room waiting area.⁶ Their direct action forced hospital leadership to meet with activists, resulting in mandatory sensitivity training for all staff. The episode captured the raw interplay of grief, intimacy, and outrage that fueled ACT UP’s politics: personal affronts were never private, but woven into collective defiance.

This confrontation also carried echoes of an earlier protest in the Village—the 1970 Snake Pit vigil. That spring, after police raided a gay bar on West 10th Street and detained nearly 200 patrons, the harsh treatment of one arrestee, Diego Viñales, sparked an impromptu demonstration outside St. Vincent’s Hospital, where he was taken after jumping from a second-story window in fear of deportation. Hundreds of people gathered with candles, shouting “Stop the raids!” and demanding recognition of queer life and dignity.⁷ Though a decade before the first reported cases of AIDS, the Snake Pit vigil established a template: St. Vincent’s, a Catholic hospital rooted in immigrant service, would also become a flashpoint where queer grief and public protest converged. St. Vincent’s was both a sanctuary and a battleground: a place where thousands sought care, and where the community confronted the stigma and neglect that defined the epidemic.

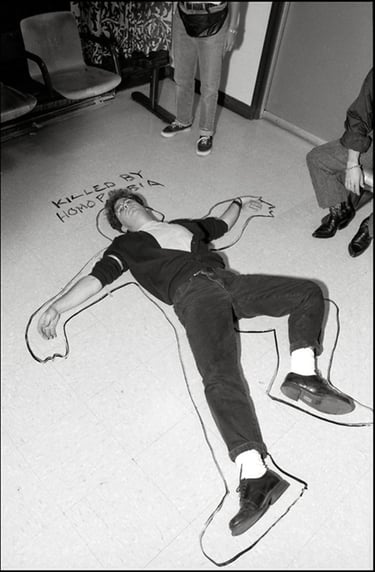

ACT UP Staging a Die-In at St. Vincent’s Hospital, 1989

In September 1989, after learning that a gay man was expelled from St. Vincent’s ER for kissing his partner, ACT UP members left their Monday night meeting and occupied the hospital’s waiting room. The protest forced administrators to meet with activists, leading to sensitivity training for all staff. Photo: t.l. litt. https://www.tllittphotography.com/gallery-image/ACT-UP-Miscellaneous-Demonstrations/G0000KV8w.FdaAxE/I0000URiEneGC5pk/C0000Ef8CJjL.BCk

The geography of grief extended well beyond the hospital itself. Just blocks away, Redden’s Funeral Home on West 14th Street became one of the few in Manhattan willing to embalm and bury those who had died of AIDS without discrimination or inflated costs.⁸ On West 13th Street, the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center offered another kind of refuge, hosting support groups, organizing care networks, and, in 1987, serving as the birthplace of ACT UP. Its rooms became spaces where mourning turned into political action, and where community solidarity confronted stigma head-on. Other Village landmarks, Christopher Street, the Hudson River piers, and St. Veronica’s Church served as stages for vigils, shrines, and protests that transformed private mourning into public testimony. At the center of this constellation stood St. Vincent’s, embodying both the devastation of the epidemic and the defiance it provoked.

When the hospital closed in 2010, many feared its history would be erased by luxury development. The memorial’s 2016 dedication at St. Vincent’s Triangle ensures the memory remains anchored in place. Dave Harper, Executive Director of the New York City AIDS Memorial, explained the tension: “Having a memorial almost indicates that something is in the past—and AIDS is not.” He emphasizes why programming matters: it’s what “makes it live and breathe and feel alive,” keeping grief and resilience present in the city’s daily life.¹⁰

Notes

“St. Vincent’s Hospital Manhattan,” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, accessed September 25, 2025, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/st-vincents-hospital-manhattan/.

Larry at The Outfront, “St. Vincent’s Hospital Epicenter of New York City’s AIDS Epidemic: Remembered,” June 6, 2019, https://theoutfront.com/st-vincents-hospital-epicenter-of-new-york-citys-aids-epidemic-remembered/.

Ibid.

Gale Ambassadors, “The Homophobic Response to the AIDS Crisis in the 1980s,” The Gale Review, May 17, 2017, https://link.gale.com.

Larry at The Outfront, “St. Vincent’s Hospital Epicenter of New York City’s AIDS Epidemic: Remembered.”

T.L. Litt, “John Kelly, Jamie Bauer, Julie Clark, and Diane Curtis – St. Vincent’s Hospital Zap,” ACT UP Alumni Photos, 1989, https://www.tllittphotography.com/gallery-image/ACT-UP-NY-Alumni-Photos/G0000qcWJT_AUWw8/I0000YFMtTx2NSeE/C0000Ef8CJjL.BCk.

David Carter, Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004), 242–243.

Jane Gross, “Funerals for AIDS Victims: Searching for Sensitivity,” New York Times, September 27, 1987, https://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/27/nyregion/funerals-for-aids-victims-searching-for-sensitivity.html.

Anemona Hartocollis, “St. Vincent’s Hospital, a Catholic Institution in New York, Will Close,” New York Times, April 7, 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/07/nyregion/07stvincent.html.

NYC AIDS Memorial, “About the Memorial,” accessed September 25, 2025, https://nycaidsmemorial.org.

Housing Works activists at the NYC AIDS Memorial, World AIDS Day 2024. Carrying signs that read “Enhance PrEP Access,” “Invest in Jobs for HIV+ Workers,” “Support New Yorkers Aging with HIV,” and “We’re Still Here,” advocates linked remembrance with urgent demands for equity. Their presence underscores the memorial’s role as a living site of activism, where the fight for dignity and justice continues alongside mourning. Photo by Rebecca Greenberg. https://ny1.com/nyc/manhattan/health/2024/12/02/new-yorkers-commemorate-world-aids-day-with-reading-of-the-names

The Development of the NYC AIDS Memorial

The NYC AIDS Memorial was not initiated by the state but by a coalition of activists, preservationists, and community members who refused to allow the memory of the epidemic to be erased. In this sense, it serves as a monument to loss and a testament to the struggle for historical memory. When St. Vincent's Hospital declared bankruptcy and closed in 2010, many feared that the history of care, activism, and loss rooted there would be erased by luxury development.¹⁴ But in the midst of redevelopment plans, the city's requirement to set part of the site aside for public green space opened a critical window for commemorative vision.

A group of young professionals, many of whom had grown up after the worst years of the epidemic, proposed creating a memorial rooted in this land, both to remember and to educate. As Executive Director Dave Harper later reflected, the founders recognized a "missing connection" to mentors, friends, and elders lost to AIDS, people whose guidance might otherwise still be part of their lives. Born in 1982, Harper himself had never known a world without AIDS. His mother worked on HIV drug trials at St. Vincent's, and as a young gay man, he carried the sense that the epidemic was an unavoidable presence, shaping what it meant to imagine a future. For Harper and others of his generation, the memorial became a means to reconnect with those silenced voices and to make their absence visible in the city's landscape.⁵

In 2011, an international design competition brought in nearly 500 proposals. The winning concept, from Studio a+i, envisioned a soaring, angular canopy of steel triangles above a plaza of engraved granite pavers bearing lines from Walt Whitman's "Song of Myself." ¹⁶ But the original design was more ambitious: it encompassed subterranean space and a larger footprint. As Harper put it, "For financial reasons … what ended up being built was just about 10 % of what was originally envisioned." ¹⁷

Jenny Holzer played a defining role in giving the memorial its textual ground. Rather than using her own voice, she chose to engrave lines from Whitman, her selection reflecting a belief in language's ability to carry communal memory. As she explained, "Various friends, associates and I waited to learn if we would die. Some died, and the rest of us were changed and do not forget." ¹⁸ She also described her choice of poem this way: "' Song' has love, and lovely words overflowing … represents ardent unashamed people abounding… that is how and what the memorial must be." ¹⁹ Her involvement tied the memorial intimately to those who lived through the crisis, not just to its aftermath.

The process was fraught. Local residents, neighborhood boards, and city agencies each envisioned their ideal for the space: some wanted playgrounds, while others envisioned open lawns. Harper recalled, "Everyone had their own wish list of what that space should be." ²⁰ The backing of family-run developers, who incorporated the memorial into the broader redevelopment, was crucial. Political voices like Corey Johnson, then Speaker of the City Council and openly living with HIV, also fought to keep the memorial central to the project.²¹

When the memorial finally opened on World AIDS Day, December 1, 2016, it was far from a finished story. It was conceived from the start as a living memorial, not a silent monument, but a space of gathering and memory. Harper has affirmed, "Programming is what makes it live and breathe and feel alive." Today, the site is animated by annual name readings, quilt-sewing workshops, performances, exhibitions, and storytelling events.²²

Today, the NYC AIDS Memorial finds its place and purpose. It resists being relegated to a relic of history. Instead, it remains a gathering site, an argument in steel and text, and a canvas for intergenerational encounters. By placing remembrance directly over a site of care, the memorial insists that grief, activism, and memory remain woven into the streets of the Village and alive in public life.

Notes

"St. Vincent's Hospital and Triangle Park," NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, accessed December 8, 2024, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/st-vincents-hospital-manhattan/.

Dave Harper (Executive Director, NYC AIDS Memorial), interview by Joseph Golden, New York, September 2024.

"NYC AIDS Memorial," NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, accessed December 8, 2024, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/nyc-aids-memorial/.

Harper, interview by Joseph Golden.

Jenny Holzer interview, Artspace, "Some died, and the rest of us were changed," Dec. 1, 2017. Artspace

"Jenny Holzer on the creation of the New York City AIDS Memorial," Phaidon, 2017. staging-ejr4ur.phaidon.com

Harper, interview by Joseph Golden.

Andy Humm, "New York City's AIDS Memorial Dedicated," Gay City News, December 1, 2016 (on Corey Johnson's advocacy).

"Programs," NYC AIDS Memorial, accessed December 8, 2024, https://nycaidsmemorial.org/programs/.

Share Your Story

Your voice matters. If you have memories, photographs, or reflections connected to the AIDS crisis in New York City, we invite you to share them. Together we can preserve these histories and ensure they are never forgotten.