The Quilt Unfolds: AIDS, Activism, and Memory in NYC

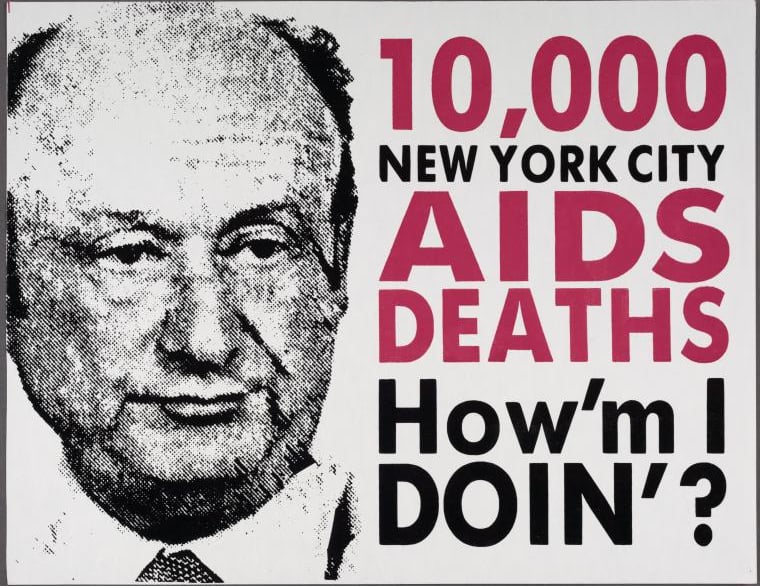

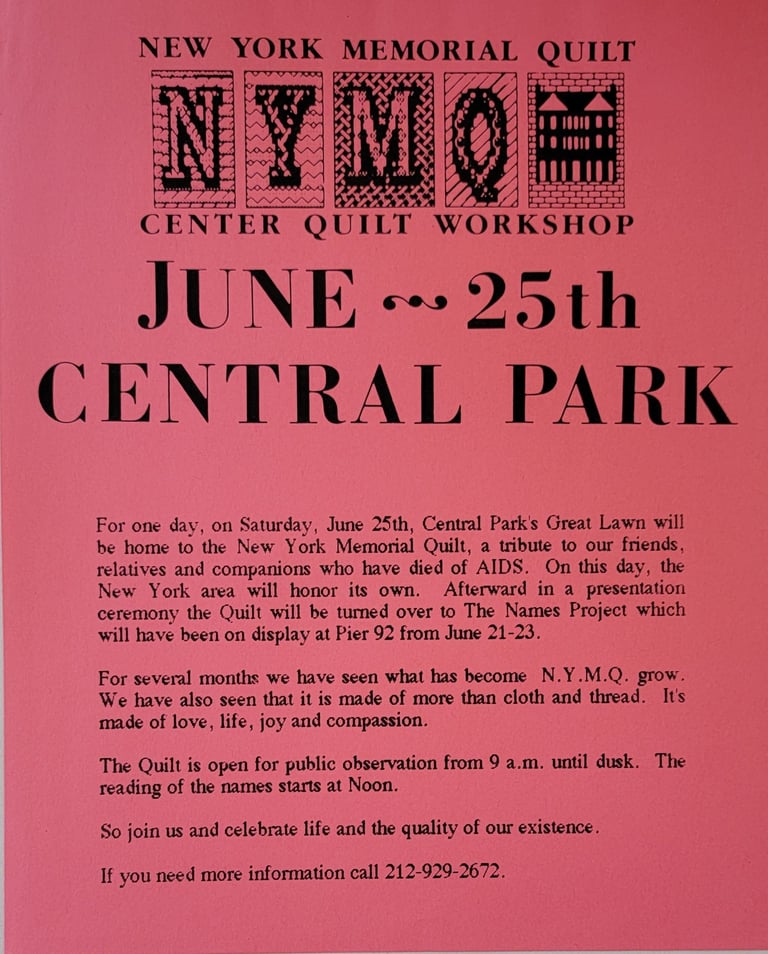

Flyer distributed during the 1988 Pride Parade. James Burke Papers, 1970–1996, Collection 44, LGBT Community Center National History Archive, processed January 30, 1996.

“NEW YORK MEMORIAL QUILT … For one day, Central Park’s Great Lawn will be home to the New York Memorial Quilt, a tribute to our friends, relatives, and companions who have died of AIDS. On this day, the New York area will honor its own… For several months we have seen what has become NYMQ [New York Memorial Quilt] grow. We have also seen that it is made of more than cloth and thread. It's made of love, life, joy and compassion... Join us and celebrate life and the quality of our existence.”

The flyer’s language highlighted the dual role of the Quilt in New York: both as part of the national NAMES Project and as a local, community-driven effort centered in the city’s own Quilt Workshop at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center. Its promise that the Great Lawn would become home to the Quilt for “one day” underscored both the temporality and the urgency of remembrance in New York, where mourning was public, improvisational, and deeply tied to the city’s activist culture. Inserting the Quilt into Pride week allowed grief to take its place alongside joy, challenging the idea that remembrance and resistance were separate acts.

When the AIDS Memorial Quilt stretched across Central Park’s Great Lawn in 1988, it transformed one of New York’s most iconic landscapes into a vast site of public mourning. More than a display, it was an invitation. Families, lovers, caregivers, and communities who had been excluded from Pride parades or political marches came to witness, grieve, and contribute. The Quilt created a space for sorrow without stigma and remembrance without spectacle, allowing grief to be made public in a city where silence and invisibility had long prevailed.

Unlike its monumental unveiling on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the New York display was fleeting. Yet its impact was profound, rooted in the local labor of the Quilt Workshop at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center, where more than 1,200 panels were created in less than a year. Here, grief was stitched into fabric, transforming mourning into communal testimony. The Quilt’s presence in New York revealed a central tension between the temporary and the enduring, between the specificity of local losses and the collective story told on a national stage.

In tracing this history, the Quilt emerges not only as a memorial but also as a political act—an assertion of dignity, a reimagining of public space, and a continuation of queer liberation strategies born in the post-Stonewall era. It expanded the terrain of remembrance by enfranchising those who had been excluded from traditional forms of mourning, making visible the diverse communities who lived and died in the epidemic’s shadow. To center the Quilt in New York is to recover a story too often overshadowed: one in which fabric, memory, and activism converged to redefine how a city, and a nation, remembers AIDS.

The AIDS Memorial Quilt: From San Francisco to Washington and Beyond

The AIDS Memorial Quilt first emerged in San Francisco from the fragile, improvised gestures of public mourning. On November 27, 1985, during the annual candlelight march commemorating the assassination of Harvey Milk, activist Cleve Jones asked mourners to write the names of loved ones who had died of AIDS on pieces of cardboard. Hundreds of signs were taped to the walls of the San Francisco Federal Building, forming a patchwork of names that fluttered in the cold drizzle before falling to the ground. Jones later recalled that, in that moment, the makeshift display “looked like a quilt.”¹ This epiphany transformed fleeting protest into a vision for a more enduring memorial.

By 1987, Jones and a group of volunteers had established the NAMES Project Foundation in a small storefront in San Francisco. The Quilt took shape as three-by-six-foot panels—the dimensions of a grave—crafted by families, lovers, and friends. Each panel bore personal objects and textures: a favorite shirt, a hand-stitched message, a piece of jewelry.² In form, the Quilt drew from traditions of domestic craft, often dismissed as “women’s work,” and turned them into radical public testimony. Its power lay in this paradox: tender and intimate in its materiality, yet monumental in its collective scale.³

Mourners Tape Names to the Façade of the Federal Building in San Francisco, November 27, 1985. Photograph. National Library of Medicine. Against the Odds: Making a Difference in Global Health. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/againsttheodds/exhibit/action_on_aids/AIDS_memorial_quilt.html.

The Quilt also belonged to a longer American tradition of craft as political resistance. From abolitionist quilting circles in the nineteenth century to suffragist banners sewn in parlors, stitching has long been a means of making private labor public when other avenues of political voice were closed.⁴ By drawing upon these traditions, the AIDS Memorial Quilt both reimagined and radicalized domestic craft. Its feminized associations with care, mourning, and home were transposed into a massive public arena, where each seam and fabric scrap became an act of defiance against silence and erasure. In this way, the Quilt joined a lineage of political textiles, transforming grief into resistance and soft fabric into a monumental form of memory.

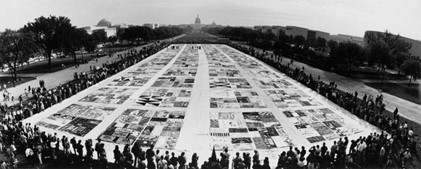

The Quilt’s first major display occurred on October 11, 1987, on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., during the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. Spanning nearly two football fields, the display featured 1,920 panels, each representing a life cut short.⁵ For many visitors, it was the first time they saw the magnitude of the epidemic visualized in such human terms. The combination of vastness and intimacy—the sheer number of panels alongside their personal details—moved tens of thousands who walked quietly among them. The display helped transform private grief into a shared national reckoning.

The NAMES Project. The Inaugural Display of the AIDS Memorial Quilt. Photograph. October 11, 1987. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt-history#:~:text=The%20Quilt%20was%20conceived%20in,the%20San%20Francisco%20Federal%20Building.

Footnotes

Cleve Jones, When We Rise: My Life in the Movement (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2016), 208–9.

Cindy Ruskin, The Quilt: Stories from the NAMES Project (New York: Pocket Books, 1988), 12.

Lawrence Howe, “The AIDS Quilt and Its Traditions,” College Literature 24, no. 2 (1997): 111–14.

Patricia Turner, Crafted Lives: Stories and Studies of African American Quilters (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009), 23–29; also Rozsika Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (New York: Routledge, 1984).

The NAMES Project, “The Inaugural Display of the AIDS Memorial Quilt,” photograph, October 11, 1987, AIDS Memorial Quilt History, https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt-history.

Jones, When We Rise, 223; Richard Berkowitz, “RetroPOZ: Surviving the Plague Years,” POZ, February 1997, archived at https://web.archive.o

The Quilt in New York City

The Quilt’s arrival in New York City was both inevitable and transformative. In a metropolis where mourning and activism overlapped daily, the Quilt became more than a memorial—it became a mirror of crisis. Confronted with homelessness, addiction, racism, and staggering AIDS deaths, New Yorkers received the Quilt less as a gentle gesture of reflection than as a raw confrontation. However soft its fabric, it carried jagged edges in New York, where stitched names linked private grief to public outrage and demanded recognition of loss.

This reception diverged from San Francisco’s more contemplative embrace of the Quilt. Each city, shaped by its own politics and social realities, produced a distinct memorial culture: San Francisco’s was spiritual and communal, while New York’s was urgent, diverse, and defiant.

Skepticism among New York activists highlighted this divide. Vito Russo, the founder of the Gay Activists Alliance and later a leader of ACT UP, initially dismissed the Quilt as “so California.”¹ Yet he went on to stitch two panels himself, showing how even the most militant critics came to see its power as political mourning. Richard Berkowitz likewise recalled unease at the 1983 Denver Health Conference, where New Yorkers bristled at San Francisco’s emphasis on hugging and spiritual reflection—a contrast to New York’s preference for confrontation.²

These differences foreshadowed later memorials. San Francisco’s National AIDS Memorial Grove, dedicated in 1996, provides a serene sanctuary for quiet reflection. New York’s AIDS Memorial, dedicated in 2017, is stark and angular, foregrounding absence and urban harshness. In this context, the Quilt in New York could never be passive. It was charged with the urgency of grief and activism, embodying remembrance as a form of resistance.

Harvey Fierstein crafts a Quilt panel that honors members of the Broadway production of La Cage aux Folles at the Quilt Project Workshop with Candida Scott Piel, Wes Cronk, and David Nimmons. February 2, 1988. Stonewall National Monument (NPS), "AIDS Memorial Quilt Panel Honoring La Cage aux Folles," Facebook, June 23, 2022, https://www.facebook.com/StonewallNationalMonumentNPS/photos/a.477674182979751/1275843403162821.

When the AIDS Memorial Quilt arrived in New York City in 1988, it transformed public space into a landscape of grief, love, and protest. Spread across the Great Lawn in Central Park, thousands of hand-stitched panels carried names, faces, and belongings of people lost to AIDS. Each square was intimate, yet together they created a collective archive that statistics alone could never capture.

Much of that work began in Greenwich Village at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center on West 13th Street. A former public school turned community hub in 1983, the Center had quickly become the heart of queer New York. It hosted ACT UP meetings, support groups, art performances, and vigils—making it both a sanctuary and a headquarters for activism. In February 1988, the New York Quilt Workshop opened on the ground floor, adding another layer to the Center’s role as a refuge and organizing space.

Inside, the workshop buzzed with activity. Sewing machines hummed, fabric hung from walls, and volunteers bent over panels. Parents, partners, friends, and strangers stitched side by side, turning private mourning into collective remembrance. Families who could not sew but sent letters and donations and entrusted volunteers to keep their loved ones’ names alive. The panels created here were not only memorials—they were acts of defiance against silence and stigma.

The Workshop embodied the Center’s dual mission: to nurture community and fuel public action. Many volunteers were themselves living with AIDS, and their presence infused the space with both urgency and tenderness. As coordinator, Wes Cronk explained, “People seem to leave their attitudes at the door. They come in ready to help one another, to be compassionate, supportive, and generous.” In this way, the Workshop became more than a sewing room. It was therapy, activism, and archive all at once—a place where grief and protest stitched themselves into history.

When displayed in Central Park and later across the city, the Quilt carried with it the spirit of the Center. In New York—dense, diverse, and in the throes of overlapping crises of homelessness, addiction, racism, and public health inequities—the Quilt could not remain a gentle gesture alone. It became both a memorial and an indictment, demanding visibility, compassion, and justice. For the public, it was a lifeline of memory; for historians, it remains a powerful example of how communities created their own archives when institutions failed them.

Mark Johnson and two unnamed volunteers stitch panels into blocks in the lobby of the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center. NYC, 1988. Courtesy of Mark Johnson from his private collection.

The Stories Behind the Stitching

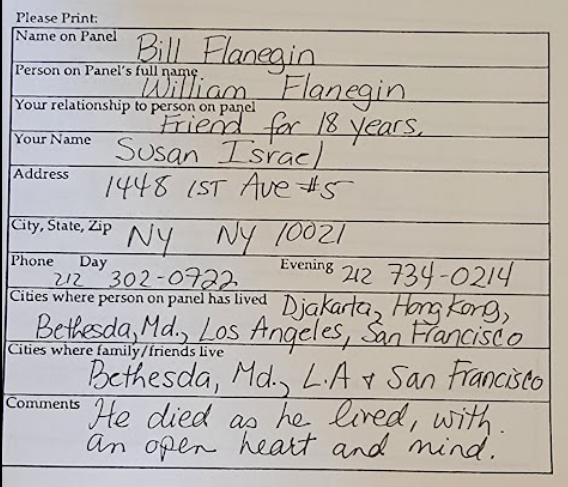

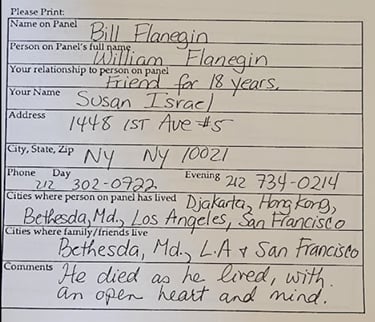

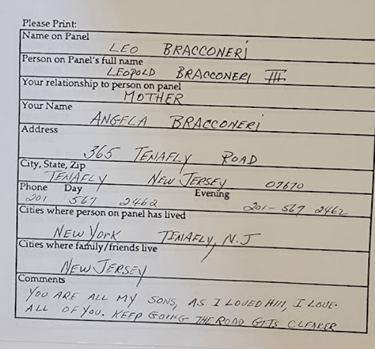

Each panel made at the New York City Quilt Workshop began not with fabric, but with a piece of paper. Every submission included a $5 donation and a memorial record that asked for a name, a relationship, and a few words of tribute. These simple forms, now preserved in the LGBT Community Center Archive, reveal a more intimate layer of the Quilt. Some records read like love letters, full of warmth, humor, and small details that captured a life. Others were sparse, written with the restraint of people carrying heavy grief. The handwriting itself often spoke volumes — shaky letters traced by parents, quick notes from friends, careful lines from partners who wanted every word to be just right.

Filling out a form could also mean making hard choices. Should AIDS be named? Should a last name be included? For some, telling the truth was an act of pride and defiance. For others, especially families who feared stigma, it was too great a risk. Some records left words blank, others wrote around what could not yet be said. Taken together, these submissions remind us that the Quilt was more than fabric. It was also a collection of voices, each one deciding how to remember, how much to reveal, and how to love in public. They show us that mourning was not quiet or hidden. It was inscribed, one word at a time, into a record that still speaks today.

Panel for Bill Flanegin includes a note from a friend of eighteen years, who wrote that Bill “died as he lived, with an open heart and mind.” In foregrounding enduring friendship and emotional intimacy, the tribute resists normative ideas of legacy rooted in biology or conventional family.

James Burke Papers, 1970–1996, Collection 44, LGBT Community Center National History Archive, processed January 30, 1996.

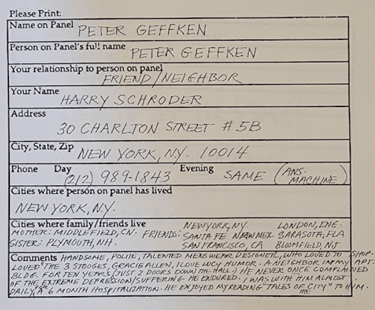

Peter Geffken’s tribute evokes camp, nostalgia, and media-inflected memory. His affection for Gracie Allen, I Love Lucy, and Tales of the City connects his story to a shared cultural archive shaped by humor, irony, and survival.

James Burke Papers, 1970–1996, Collection 44, LGBT Community Center National History Archive, processed January 30, 1996.

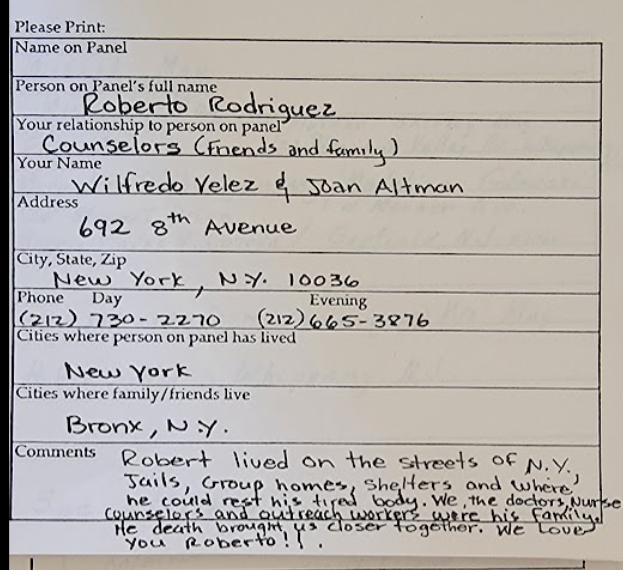

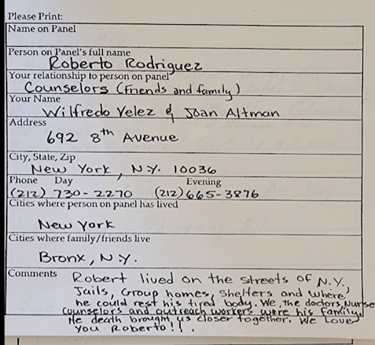

Roberto Rodriguez, a homeless man who cycled through hospitals, shelters, and jails, had no family left to grieve him. His panel was made by the outreach workers who had become his chosen family. “Robert lived on the streets of N.Y. jails, group homes, where he could rest his tired body. We, the doctors, nurses, counselors, and outreach workers, were his family,” they wrote. “His death brought us closer together."

James Burke Papers, 1970–1996, Collection 44, LGBT Community Center National History Archive, processed January 30, 1996.

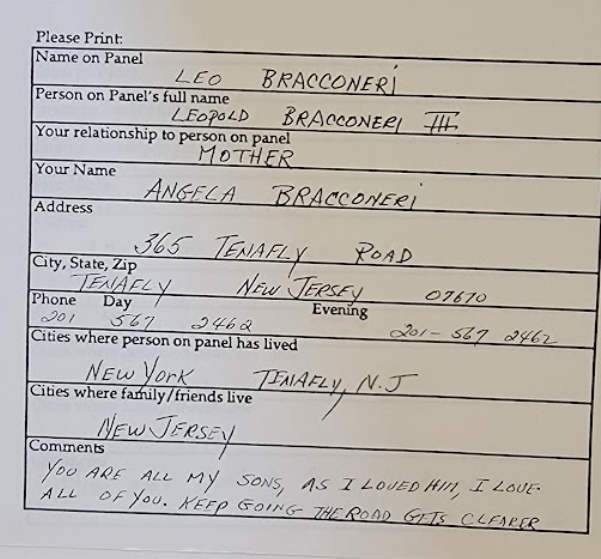

Other tributes were grounded in the universal language of familial grief. The panel for Leo Bracconeri featured a heartfelt message from his mother, who shared her profound sorrow that reached far beyond her loss. You are all my sons, she wrote. As I loved him, I love all of you. Keep going, the road gets clearer.

James Burke Papers, 1970–1996, Collection 44, LGBT Community Center National History Archive, processed January 30, 1996.

Radical Inclusion: The Quilt in New York

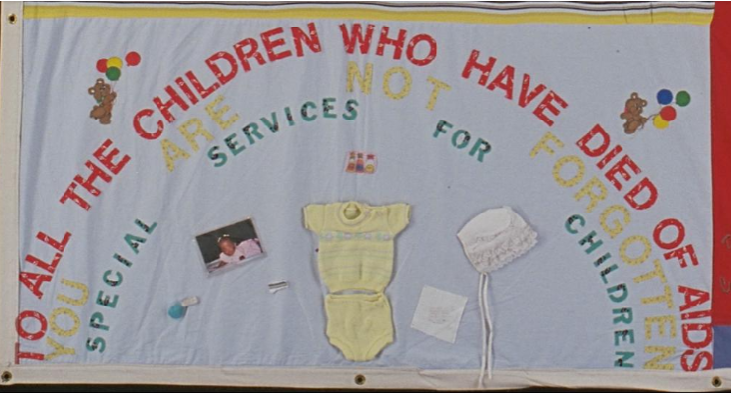

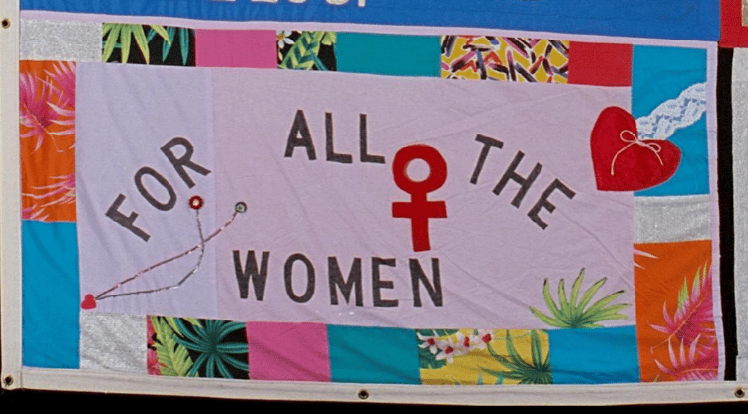

The AIDS Memorial Quilt has often been criticized for focusing too heavily on the stories of white gay men. But the panels created at the New York City Quilt Workshop tell a broader and more complicated story. In their diversity, they reflected a city where the epidemic touched everyone: women, children, IV drug users, the unhoused, healthcare workers, social workers, and many others whose lives were too often erased from public accounts.

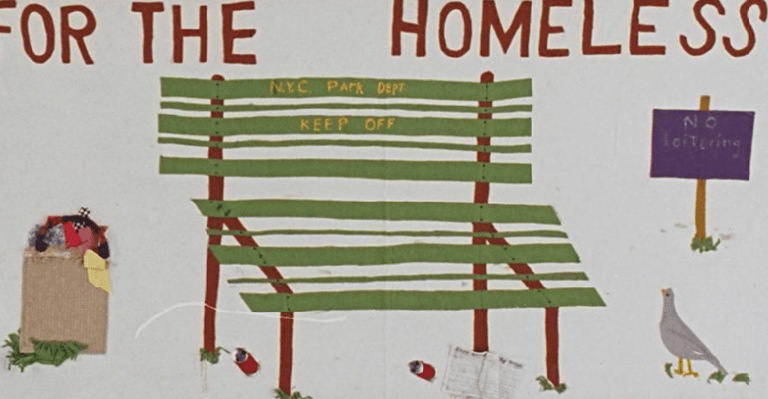

Not every panel carried a name. Some were dedicated to children or to the homeless, created by those who cared for them when no relatives remained. Other panels were stitched with love but deliberately withheld full names or details, reflecting the difficult balance between honoring the dead and protecting them—or their families—from stigma. Still others broke from the Quilt’s grammar of tenderness altogether, using fabric not to console but to confront, refusing reconciliation and forcing viewers to grapple with painful truths.

Together, these submissions reveal the Quilt as more than a memorial of love and loss. It was also a record of absence, censorship, conflict, and resistance. In New York, the Quilt became a space where remembrance could take many forms: quiet, celebratory, defiant, or accusatory. Its power lay not only in what was displayed, but also in what was withheld—and in how communities struggled with the question of who could be remembered, and how.

Panels for children were among the most haunting. Agencies like Special Services for Children submitted tributes on behalf of young lives lost too soon. One block bore a simple message: “To all the children who have died of AIDS: You are not forgotten.” It stood in for countless names never recorded, for children who died without ceremony or surviving kin. All the Children. Block # 1037 (04). National AIDS Memorial. “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

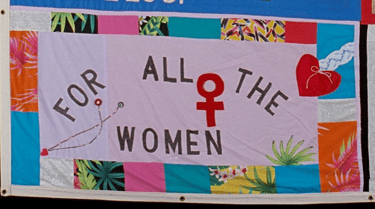

Women, too, found visibility on the Quilt. Organizations like the Women in the AIDS Resource Network honored women as people living with HIV, as caregivers, and as mourners. Their panels made clear that AIDS was never only a male story. National AIDS Memorial. “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt..

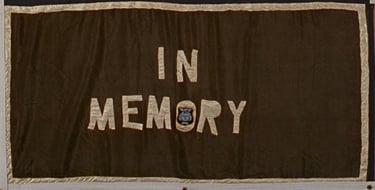

The Quilt even received contributions from institutions not usually associated with mourning. The New York Police Department submitted one panel—a plain design bearing only a badge and the words “In Memory.” Its quiet minimalism contrasted with the colorful, expressive language of most Quilt panels, yet its presence carried weight. However small, it marked an acknowledgment of loss by a department often seen as indifferent or hostile to AIDS-affected communities. NYPD #41982. Block # 949 (4). National AIDS Memorial. “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

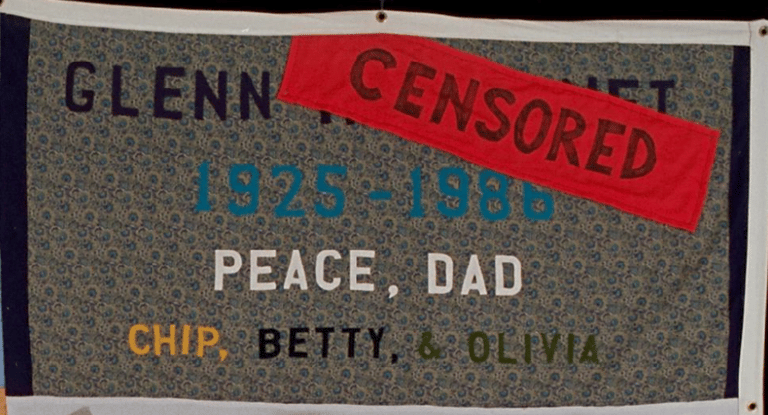

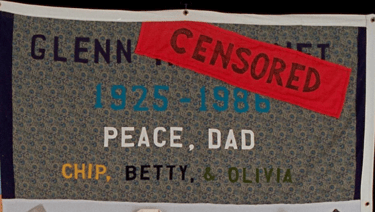

To submit a panel sometimes meant outing someone after death. Families often resisted AIDS-related symbols, erased same-sex partners, or negotiated compromises. One such example is the panel for Glenn [Censored], lovingly stitched by his children. They withheld his surname but refused silence, creating a tribute that honored him without exposing what he had kept private in life. His panel reveals how remembrance often required difficult choices, balancing love, secrecy, and stigma. Quilt panel for Glenn [Censored]. Block # 639 (01). National AIDS Memorial. “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

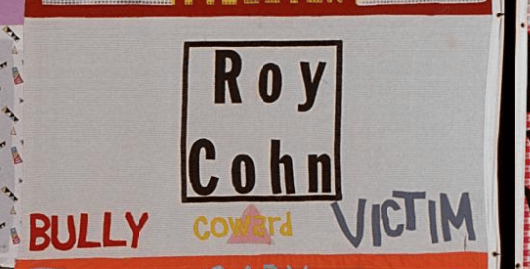

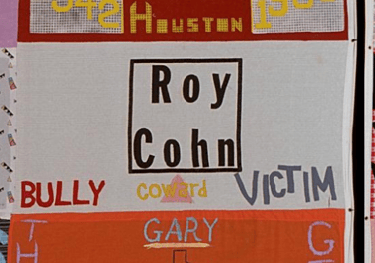

Some panels broke away from the Quilt’s usual language of love and mourning. They did not simply grieve; they accused. One of the most striking examples is the panel for Roy Cohn, the powerful lawyer who spent his career persecuting queer people during the McCarthy era, advised Donald Trump, and fought against AIDS policy even as he lived and died with the disease. His panel displayed a pink triangle with the words “bully,” “coward,” and “victim.” Unlike the panels that tenderly remembered sons, lovers, or friends, this one refused forgiveness. Block # 104 (04) National AIDS Memorial. “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

Nearby, another panel remembered those who rarely made it into the news or the archives: people who died homeless, without names, families, or funeral services. It stood as both a memorial and a protest. It asked viewers to see the lives that society had long ignored, even before AIDS made their disappearance complete.“AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

Together, these panels remind us that remembrance is never neutral. The Quilt was not only an act of love, it was also a demand for justice, a way of saying that every life lost to AIDS, whether powerful or forgotten, deserves to be seen.

Previewing the New York Quilt, Spring 1988

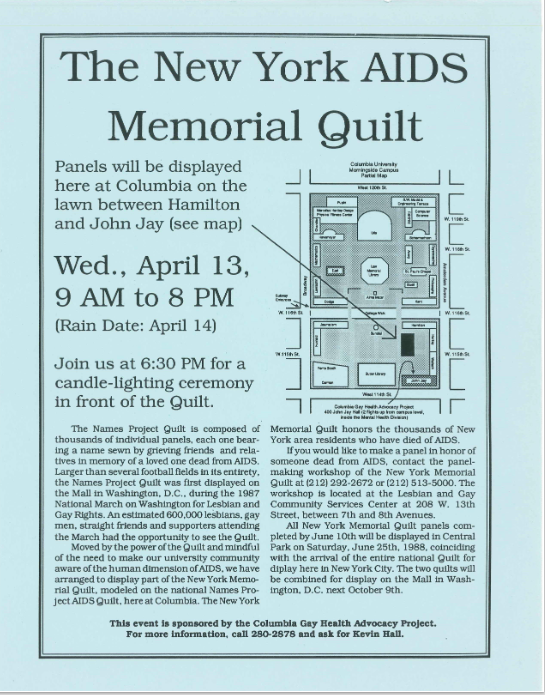

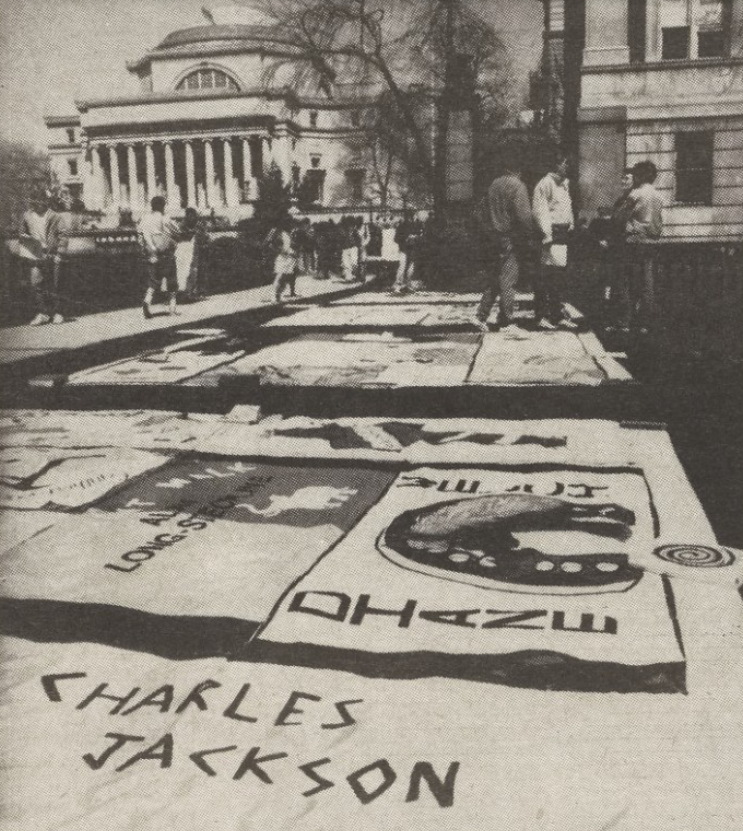

By the spring of 1988, after months of panel-making by hundreds of New Yorkers, the New York Quilt received its first public preview on April 13 at Columbia University’s Morningside campus. The setting, steeped in Ivy League privilege and institutional authority, stood in striking contrast to the Quilt’s grassroots origins. Organized by the Columbia Gay Health Advocacy Project (GHAP), the event placed AIDS remembrance at the symbolic center of elite academic life. Framed by neoclassical architecture, Hamilton Lawn became a temporary site of public mourning and political visibility.

Flyer for the AIDS Quilt display at Columbia University, 1988. James Burke Papers, 1970–1996, Collection 44, LGBT Community Center National History Archive, processed January 30, 1996.

Unlike activist-driven displays at Pride marches or in public parks, this showing was a deliberate attempt to spark awareness in a community often insulated from the epidemic’s immediate toll. The decision to bring the Quilt to Columbia was as much about visibility as it was about remembrance. Organizers sought to evoke empathy in a setting where AIDS was too often treated as distant or abstract. The event concluded with a candlelight vigil attended by approximately fifty people. In the reading of names and the glow of candles, academic ceremony merged with activist ritual, turning a campus lawn into a space of community grief.

The AIDS Quilt is displayed on Hamilton Lawn at Columbia University. Columbia Daily Spectator, April 14, 1988. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://ghaparchive.health.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/Spectator/1988/AIDS%20quilt%20on%20Hamilton%20lawn%20honors%20New%20Yorkers%20who%20died%20of%20the%20disease%2014%20November%201988.pdf.

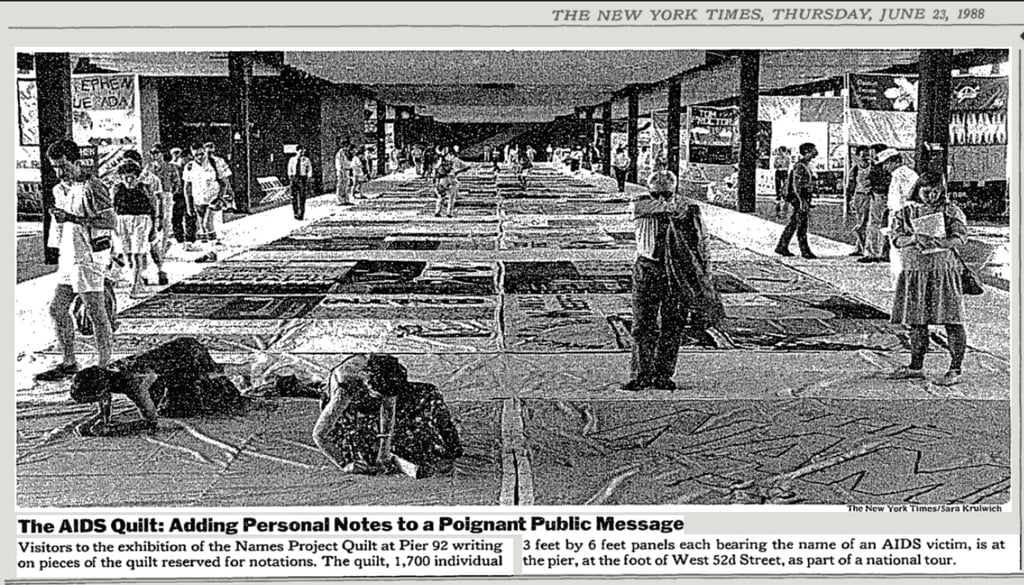

Names Project Quilt display at Pier 92 in New York City, New York Times, photo by Sara Krulwich. https://www.nytimes.com/1988/06/23/nyregion/the-aids-quilt-adding-personal-notes-to-a-poignant-public-message.html

The Quilt in New York: Politics, Culture, and Conflict

The AIDS Memorial Quilt was launched in San Francisco in 1987 and quickly became a national memorial project under the stewardship of the NAMES Project Foundation. Conceived as a unifying gesture of compassion and remembrance, it traveled from city to city on a national tour that culminated in its return to Washington, D.C., for a massive display on the National Mall in October 1988. Along the way, the Quilt stopped in New York during Pride Week, transforming the city’s spaces into temporary sites of public mourning and political reckoning.

From the beginning, tensions shaped how the Quilt would be presented in New York. In a letter dated May 3, 1988, Paul Halsall of New York’s host committee wrote to Michael Smith of the NAMES Project Foundation to confirm hard-won agreements: the Central Park display would not be referred to as an “unfolding,” nor would it replicate the Foundation’s ceremonial format. Local organizers Wes Cronk and Candida Scott Piel were tasked instead with designing an event that reflected New York’s own ethos—part activist ritual, part communal mourning, and fiercely independent.¹

The contrast with the NAMES Project’s vision was stark. Cleve Jones, who founded the Quilt, described it as “not political,” emphasizing unity and healing.² In New York, where the epidemic had already devastated entire neighborhoods and galvanized movements like ACT UP, many insisted it could not be anything but political. As one New York Times report observed during the city’s 1988 exhibitions, the panels were not only memorials but also “poignant public messages” that demanded recognition in a society that too often turned away.³

The differences became visible in practice. The Quilt’s showing at Pier 92 in June 1988 was orderly and professional, in keeping with the touring model promoted by the Foundation.³ Later that same month, the display on Central Park’s Great Lawn was improvisational and raw: panels laid directly on the dusty grass, volunteers struggling to keep them intact, and the noise of music and announcements competing with quiet remembrance. Both events were committed to honoring the dead and giving visibility to the epidemic, but they embodied competing visions. At Pier 92, the Quilt reflected cohesion and solemnity. In Central Park, it reflected New York’s traditions of protest and urgency, transforming mourning into resistance.

Behind these differences lie larger questions about memory and control. The May 3 letter outlined the roles of three entities: the NAMES Project Foundation, the New York Quilt Workshop at the LGBT Community Center, and the host committee for the Central Park event. After the Pride Week display, the panels created in New York were formally handed to the NAMES Project Foundation, each accompanied by a $5 incorporation fee. Local stewardship ended, and New York’s contribution was absorbed into the national Quilt.

Yet New York’s Quilt was not simply a stop on a national tour. Shaped by staggering loss, radical activism, and the city’s unparalleled cultural vitality, it represented something singular: massive, imperfect, temporary, and deeply personal. It carried the voices of activists, caregivers, artists, and families into one of the city’s most visible public spaces. For New Yorkers, mourning was never separate from action. On the Great Lawn, grief itself became resistance.

¹ Paul Halsall to Michael Smith, May 3, 1988, James Burke Papers, 1970–1996, Collection 44, LGBT Community Center National History Archive.

² Cleve Jones, When We Rise: My Life in the Movement (New York: Hachette Books, 2016), 219.

³ David W. Dunlap, “Quilt Unfolds Painful Story of AIDS,” New York Times, June 20, 1988, Sec. B, p. 3.

In June 1988, visitors gathered on Central Park’s Great Lawn to honor those lost to HIV/AIDS, as the AIDS Memorial Quilt was unfurled across the dusty field. For one day, the park became a space of mourning, remembrance, and resilience. Courtesy of NYC Parks Archives, nycgovparks.org

On Sacred Ground: Queer Memory in the Park

On Sunday, June 25, 1988, following New York’s Pride March, the AIDS Memorial Quilt was unveiled on the Great Lawn of Central Park. The morning began with music, floats, costumes, and chants that filled Manhattan’s streets, but it ended in solemn reverence. Along the parade route, volunteers had distributed hundreds of red Xeroxed flyers, inviting marchers not to the festival at the end of Christopher Street but to the park. The message promised something different: not celebration, but remembrance.¹

For generations, Central Park carried layered meaning for LGBTQ+ New Yorkers. It was a space of intimacy, risk, and coded visibility. In Gay New York, historian George Chauncey notes that the Great Lawn was nicknamed “the Fruited Plain” by gay men as early as the 1920s.² Yet pleasure was never separate from danger. Plainclothes police routinely staged stings and arrests as part of a broader campaign to criminalize queer life. Even so, LGBTQ+ New Yorkers continued to claim the park as their own. It was the site of the first Christopher Street Liberation Day Rally in 1970, when thousands gathered in the Sheep Meadow to celebrate visibility in the wake of Stonewall.³ Through the 1970s and early 1980s, the park remained a stage for protest, leisure, and community—where bodies gathered in joy, in defiance, and eventually, in grief.

By the late 1980s, the Great Lawn itself reflected the city’s wider decline. Known locally as “the Great Dustbowl,” it had become a barren expanse of dirt, symbolic of neglect during New York’s fiscal crisis. For many unhoused people, including those living with AIDS, the park became a refuge after hospitals and housing programs failed.⁴ The Lawn stood as a visible marker of abandonment, its deterioration mirroring the erosion of the city’s public health infrastructure.

Against this backdrop, the Quilt remade the space. On June 25, fabric stitched by thousands of hands covered the Dustbowl, turning a neglected field into sacred ground. The unveiling was more than symbolic. In a city where the epidemic’s toll was staggering and government response painfully slow, the Quilt asserted its presence. It transformed the heart of New York into a visible field of memory, grief, and resilience. Some were drawn intentionally by the flyers; others stumbled upon the display by chance. On one side of the Lawn, families picnicked and tossed frisbees. On another, mourners walked in silence among the panels. The juxtaposition captured the city’s fractured response to AIDS: grief and indifference, visibility and disregard, existing side by side

Central Park, long contested ground for queer New Yorkers, had been transformed—if only for one day—into sacred space. It became a place of mourning, resistance, and collective memory.

Notes

¹ Flyer distributed during the 1988 Pride Parade, James Burke Papers, 1970–1996, Collection 44, LGBT Community Center National History Archive.

² George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 340.

³ Diana Davies, “Gay-In” at the Sheep Meadow, Christopher Street Liberation Day March, June 28, 1970, New York Public Library.

⁴ David W. Dunlap, “Quilt Unfolds Painful Story of AIDS,” New York Times, June 20, 1988, Sec. B, p. 3.

James Burke Papers, 1970–1996, Collection 44, LGBT Community Center National History Archive, processed January 30, 1996.

Fabric of a City: The Cultural and Political Texture of the AIDS Memorial Quilt in New York

The 1988 display of the AIDS Memorial Quilt in Central Park survives today in fragments: news photographs, flyers distributed during Pride, press clippings, and the memorial forms preserved in the LGBT Community Center Archive. Most crucially, the meticulous record-keeping of Jim Burke, a volunteer and co-coordinator of the New York Quilt Workshop, makes it possible to reconstruct the day with unusual precision. Burke saved everything—letters, schedules, budgets, and memorial forms—ensuring that this fleeting event left behind a detailed archive. Without his diligence, much of the lived texture of the New York display would have disappeared.

The Quilt’s unveiling was not a standalone memorial but the culmination of Pride weekend. On the morning of Sunday, June 25, 1988, the city had surged with sound and color: floats, costumes, chants, and music rising through the streets. As the parade marched south, volunteers pressed red Xeroxed flyers into outstretched hands, inviting participants to continue the day not at the festival on Christopher Street but on the Great Lawn of Central Park. There, a different gathering awaited—not a celebration, but a remembrance. As the Quilt was laid out in twelve-by-twelve-foot blocks bordered with hand-dyed cotton donated by Japanese artist Hiroshi Saito, dust clouds rose into the air. Volunteers swept dirt from panels with brooms, a gesture at once practical and symbolic: acts of care performed against the backdrop of civic abandonment. A surviving home video—grainy and handheld—captures this atmosphere vividly, showing sequins glinting in sunlight as fabric rippled in the breeze, even as dust clung stubbornly to the cloth.¹

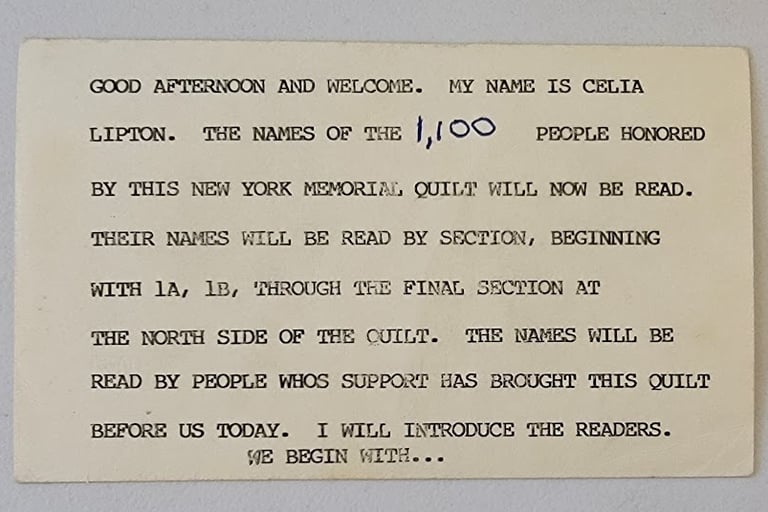

At noon, the reading of names began. One by one, voices called into the open air, each syllable lifted into public memory. People knelt by the panels, some leaving flowers or photographs, while others sat quietly in reflection. Grief counselors, marked with lavender armbands, circulated gently, ready to steady those overtaken by grief. The ritual echoed the national NAMES Project displays, where silence and order defined the tone. Yet in New York, the context was less controlled. On the margins of the Lawn, loudspeakers carried speeches and music, promotional announcements drifted through the crowd, and the hum of city life intruded. This unsettled balance between reverence and disruption reflected the city’s ethos: grief was public, messy, and confrontational here.

Not everyone found the juxtaposition moving. Hal Rubenstein, in a letter preserved in the archive, condemned the setting as a “sandbox” and lamented, “All that time, all that effort, all that creativity spent creating a loving memorial only to have it presented in dirt. … Silence would have been appreciated.”² His frustration points to the gap between the solemn unity that Cleve Jones and the NAMES Project envisioned for the national Quilt and the rawer, improvisational approach of New York. Where Washington, D.C. sought to console, New York demanded visibility, even if it meant contradiction. By mid-afternoon, the day shifted. The slow cadence of names gave way to a rally, as musicians performed and speakers called for action. Pamphlets on HIV/AIDS and safer sex circulated through the crowd, while buttons and posters were sold to sustain the Quilt and support local organizations.

As evening approached, the New York panels were formally handed over to representatives of the NAMES Project Foundation, affirming their incorporation into the national memorial. The handoff symbolized both inclusion and loss: a local creation, forged in the city's urgency, was being absorbed into a broader, more ordered narrative. At sunset, the Healing Circle guided a candlelight vigil and purification ceremony. Participants encircled the Quilt with candles, their soft glow flickering against the dusty expanse. Volunteers folded each section with deliberate care, lifting it from the ground until only the candlelight remained.

For one day, the Great Lawn, usually a site of neglect and public indifference, was remade into sacred ground. It was a place where mourning became resistance and where New York’s voice—fierce, public, and defiant—reshaped a national memorial into something distinctly its own.

Notes

AIDS Memorial Quilt Display – Central Park NYC – June 25, 1988, YouTube video, 11:13, posted by “Peter Carley,” May 15, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cAb7c3qNPEE&t=526s.

Hal Rubenstein letter, May–June 1988, James Burke Papers, 1970–1996, Collection 44, LGBT Community Center National History Archive.

David W. Dunlap, “Quilt Unfolds Painful Story of AIDS,” New York Times, June 20, 1988, Sec. B, p. 3.

Visitors write messages on the hand-dyed cotton donated by Japanese artist Hiroshi Saito. Central Park NYC – June 25, 1988, YouTube video, 11:13, posted by “Peter Carley,” May 15, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cAb7c3qNPEE&t=526s.

Joey “Jazzy” Pinto

Sequins, stripes, and a feather boa give this panel its radiant presence, capturing the exuberance of New York’s queer nightlife and the brilliance of everyday performance. More than a static tribute, the panel came alive on the Great Lawn in 1988. A surviving video shows it rippling in the breeze, its textures catching the light. That movement reminds us of what photographs or digitized archives cannot fully convey—the tactile immediacy of the Quilt as a living memorial, where fabric and gesture carried memory into public space. Central Park NYC – June 25, 1988, YouTube video, 11:13, posted by “Peter Carley,” May 15, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cAb7c3qNPEE&t=526s.

The Cultural and Political Texture of the Quilt in New York

Each panel bore silent witness to a life cut short. In New York’s Quilt, anonymity existed beside notoriety, childhood innocence beside queer sexuality, and public service beside artistic brilliance. These juxtapositions expanded the Quilt’s meaning, revealing the complexity of lives lost and the multifaceted identities that defined them.

When the AIDS Memorial Quilt was unfurled on the Great Lawn in June 1988, it became more than cloth and thread. For one day, New York turned a neglected public field into sacred ground. The Quilt reflected the city’s scale of loss, its creativity, and its resilience, while also exposing the tensions of public mourning. It held stories of artists, immigrants, sex workers, health workers, parents, lovers, and children—each panel personal, yet woven into a larger collective memory.

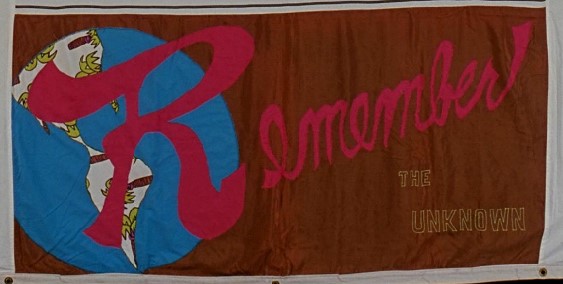

The New York Quilt also revealed silences. Many who died—those unclaimed, unnamed, or marginalized—were never sewn into its fabric. Some found their final resting place on Hart Island, buried without ceremony, their absence a haunting counterpoint to the Quilt’s public intimacy. Panels that read “Remember the Unknown” or “For the Homeless” made those absences visible, asking who gets remembered and who is left behind.

Unlike the national displays in Washington, D.C., with their solemn rituals of collective mourning, New York’s version was rawer and more improvised. It mirrored the city itself: vibrant, fractured, confrontational, and defiantly public. In this setting, mourning became resistance. The Quilt demanded recognition not only for the dead but also for the living communities still struggling to survive.

In transforming private grief into collective memory, the Quilt challenged traditional ideas of how societies mourn. It shifted commemoration away from monuments to military victories or political leaders, instead honoring the caretakers, lovers, and everyday people whose lives mattered. This was its most radical legacy: to insist that grief could be public, inclusive, and political—that remembering ordinary lives was itself an act of justice.

Roberto Rodriguez

Remembered by social workers who became his chosen family, this panel pairs his name with his Army uniform. Though homeless at the time of his death, the tribute affirms his dignity, service, and humanity in the face of neglect.National AIDS Memorial. Block # 1022 (04). “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

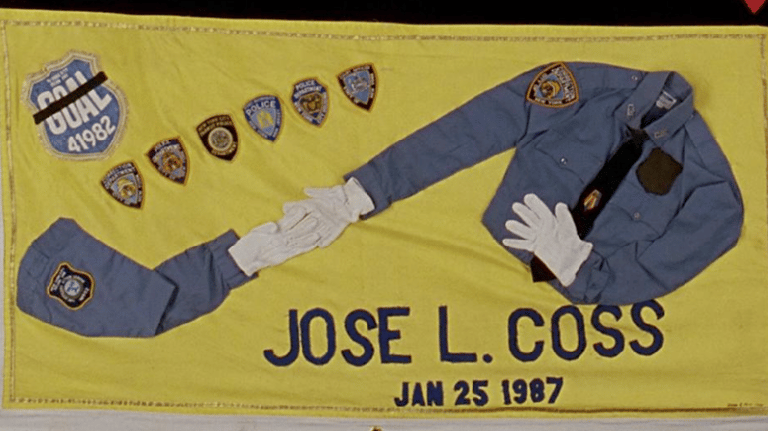

Jose L. Coss

Two police uniforms stitched hand in hand, marked with the insignia of the Gay Officers Action League. A quiet but powerful gesture of love, vulnerability, and solidarity within an institution often hostile to LGBTQ+ lives. Block # 891 (08). National AIDS Memorial. “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

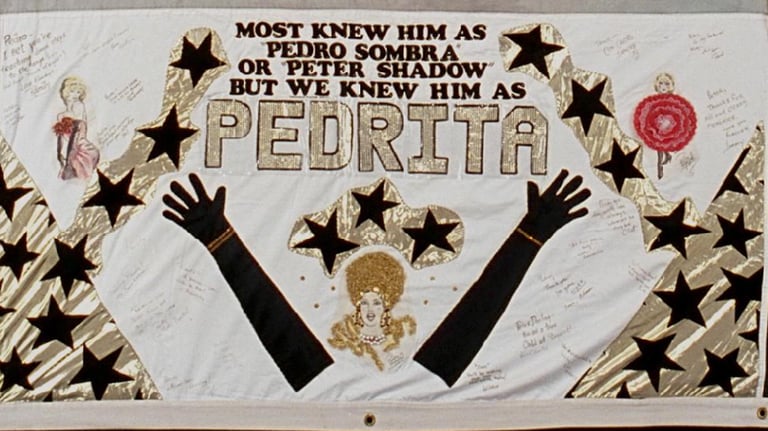

Pedro Sombra (“Pedrita”)

Friends honored Pedro through his drag persona, Pedrita, adorning the panel with gloves and handwritten messages. It captures the joy and resilience of queer nightlife and the chosen family that accompanies it. Block # 578 (04). National AIDS Memorial. “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

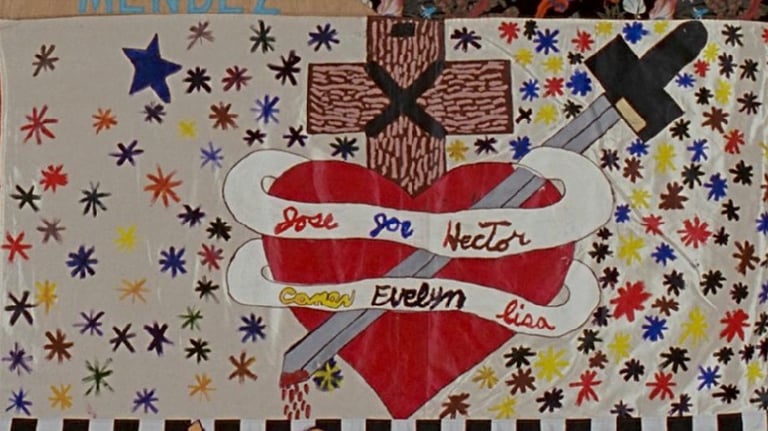

Jose, Joe, Hector, Carmen, Evelyn, Lisa

Six individuals are remembered by their first names. National AIDS Memorial. Block # 856 (06). “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

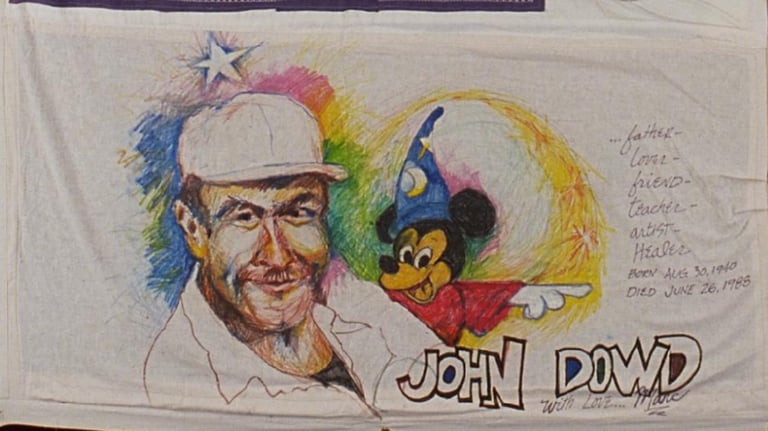

John Dowd

Described as a father, lover, friend, teacher, artist, and healer. National AIDS Memorial. Block # 748 (04). “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

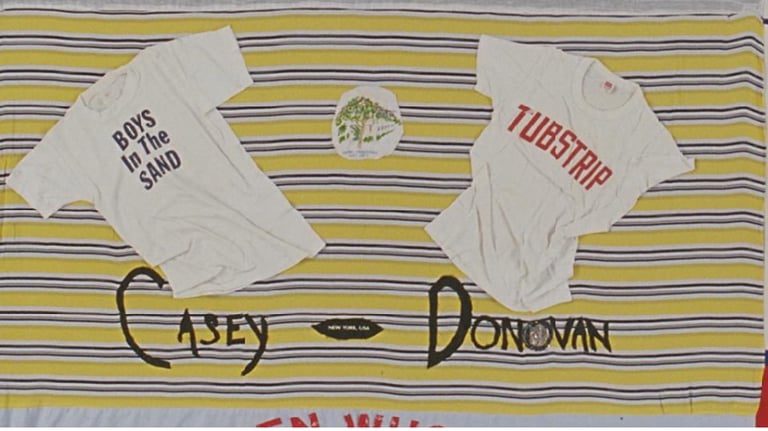

Casey Donovan

Best known as an adult film star and cultural figure of the 1970s, Donovan’s panel confronts both fame and vulnerability. It reminds viewers that AIDS cut across every sphere of public and private life, claiming even those whose lives had seemed larger than life.

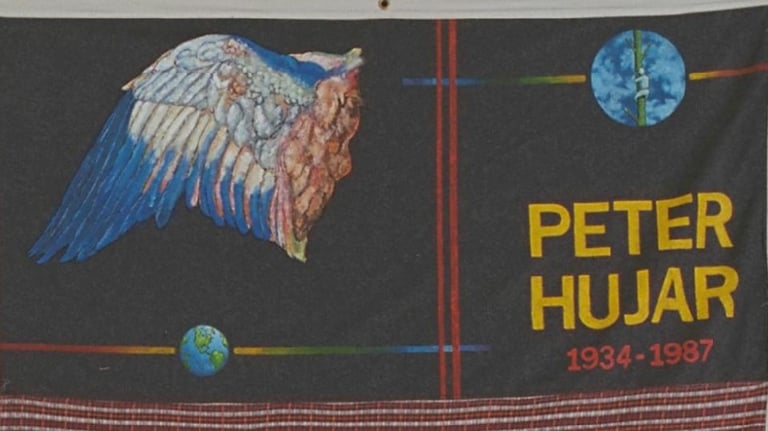

Peter Hujar

Artist David Wojnarowicz crafted this panel to honor his friend and mentor, photographer Peter Hujar. One of the most influential figures in New York’s downtown art scene, Wojnarowicz transformed his grief into art, stitching memory and protest into fabric. The panel stands as both a tribute to Hujar’s vision and an extension of Wojnarowicz’s own artistic legacy. Block # 854 (05). “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

The Unknown

Set against a somber map of the Western Hemisphere, this panel bears only the words “Remember the Unknown.” It honors those lost to AIDS whose names were never recorded, whose lives went unclaimed or unrecognized. In its stark simplicity, the panel transforms absence into testimony, insisting that even those rendered invisible by stigma or circumstance must not be forgotten. Block # 1258 (05). National AIDS Memorial. “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

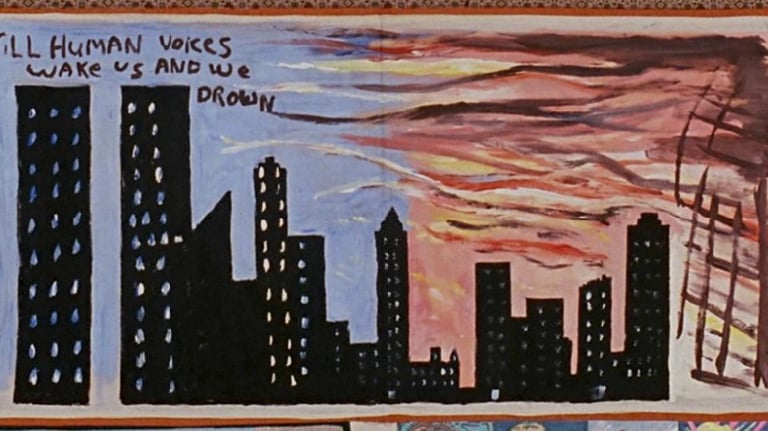

“Till human voices wake us and we drown”

This haunting line from T. S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock appears on a stark, enigmatic panel. Without images or names, it conveys the weight of silence and foreboding that surrounded the epidemic. Its words read like a warning and a lament, evoking a city sleepwalking through catastrophe and the urgency of voices that were too often ignored until it was too late. National AIDS Memorial. “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt

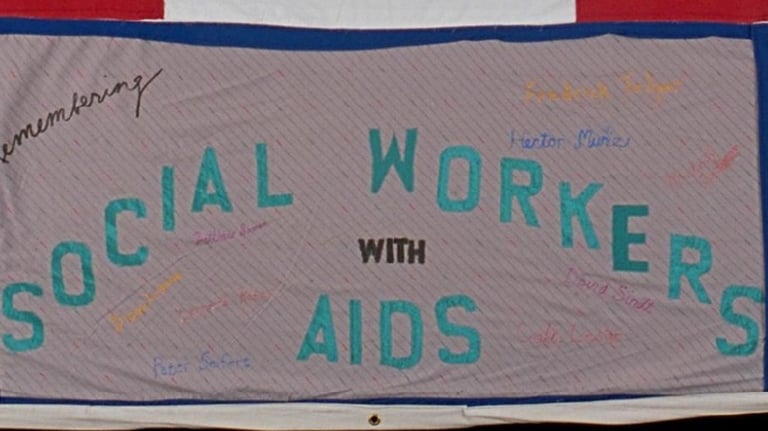

Social Workers with AIDS

This panel was created collectively by members of the group Social Workers with AIDS. Each name was written by hand, a gesture that makes the memorial feel both intimate and immediate. The absence of decorative imagery shifts the focus to the act of naming itself, underscoring how deeply entwined social workers were in the epidemic. They were caregivers, advocates, and witnesses—yet also grievers and, in many cases, people living with HIV themselves. The handwritten names reflect a community insisting that their own labor, loss, and humanity be remembered. Social Workers with AIDS. National AIDS Memorial. Block # 639 (04). “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

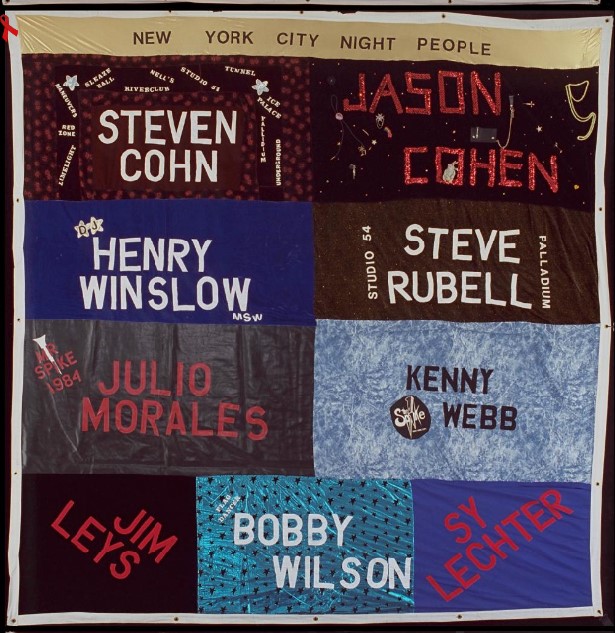

New York City Nightlife

This block commemorates the world of clubs, discos, and dance floors that defined queer New York. It remembers not only the patrons but also the bartenders, DJs, and promoters who built spaces of freedom and community. Names of venues like The Saint, Limelight, and Studio 54 appear alongside those who animated them. Among the most notable is Steve Rubell, co-owner of Studio 54, whose velvet-rope empire came to symbolize glamour, excess, and queer visibility in 1970s Manhattan. His presence on the Quilt, stitched beside nightlife workers and everyday revelers, reminds us that AIDS devastated both the famous and the anonymous, the celebrated and the unseen. Together, these panels preserve nightlife as more than entertainment—it was a vital arena of queer belonging, expression, and survival. Block # 1667. “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

A Block of Memory

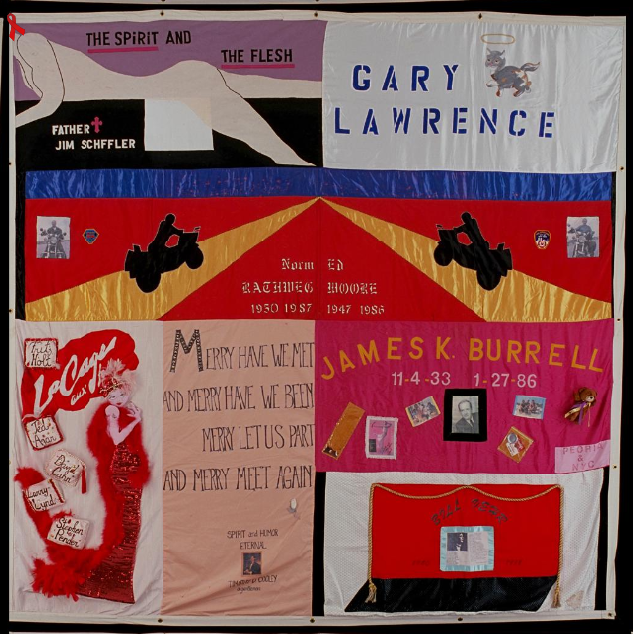

This block of the New York City AIDS Memorial Quilt brings together nine lives stitched side by side. Each square tells its own story, yet together they form a larger memorial that collapses boundaries of fame and anonymity, faith and sexuality, intimacy and public life.

Louis Nelson created one pair of panels in honor of his partner, Norm Rathweg, and Norm’s best friend, Ed Moore. “They were not lovers,” Nelson explained, “but they shared a passionate love for riding motorcycles.” Placing them together speaks to the overlapping networks of chosen family and friendship that helped sustain queer life in the midst of crisis. Other panels reflect the diversity of mourning practices: a Wiccan blessing sewn into cloth, a teddy bear and handwritten note preserved in fabric, or a single kitten with a halo symbolizing tenderness and loss.

Some panels are more provocative. The tribute to Father Jim Schffler, a Catholic priest, combines a clerical collar with the outline of a reclining man, challenging assumptions about faith, desire, and belonging. The block also includes a panel dedicated to four members of the Broadway production of La Cage aux Folles, sewn by playwright and actor Harvey Fierstein. With bold color and theatrical energy, it honors the artists lost while extending the show’s spirit of defiance and joy.

Together, the block reveals the complexity of lives lost to AIDS: partners and friends, priests and performers, tender memories and bold statements. It reminds us that grief and love were never simple, and that remembrance could be quiet, spiritual, playful, or confrontational—but always deeply human.

Block # 1048. National AIDS Memorial. “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

The Quilt’s Legacy in New York

When the AIDS Memorial Quilt was unfurled on the Great Lawn in June 1988, it became more than cloth and thread. For one day, New York turned a neglected public field into sacred ground. The Quilt reflected the city’s scale of loss, its creativity, and its resilience, while also exposing the tensions of public mourning. It held stories of artists, immigrants, sex workers, health workers, parents, lovers, and children, each panel personal, yet woven into a larger collective memory.

The New York Quilt also revealed silences. Many who died—those unclaimed, unnamed, or marginalized—were never sewn into its fabric. Some found their final resting place on Hart Island, buried without ceremony, their absence a haunting counterpoint to the Quilt’s public intimacy. Panels that read “Remember the Unknown” or “For the Homeless” made those absences visible, asking who gets remembered and who is left behind.

Unlike the national displays in Washington, D.C., with their solemn rituals of collective mourning, New York’s version was rawer and more improvised. It mirrored the city itself: vibrant, fractured, confrontational, and defiantly public. In this setting, mourning became resistance. The Quilt demanded recognition not only for the dead but also for the living communities still struggling to survive.

In transforming private grief into collective memory, the Quilt challenged traditional ideas of how societies mourn. It shifted commemoration away from monuments to military victories or political leaders, instead honoring the caretakers, lovers, and everyday people whose lives mattered. This was its most radical legacy: to insist that grief could be public, inclusive, and political—that remembering ordinary lives was itself an act of justice.

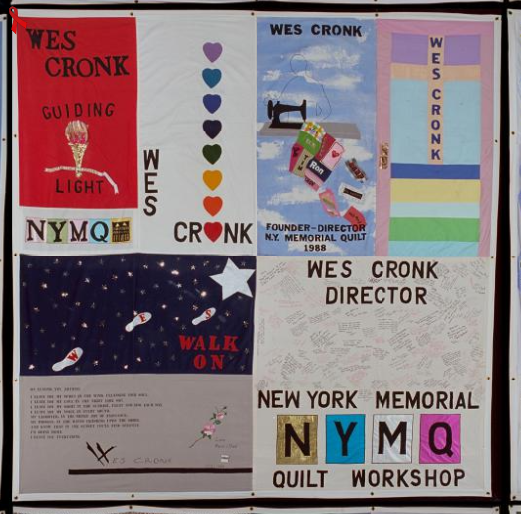

Wes Cronk

1988-1989. National AIDS Memorial. Block # 1251 (01-08). “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

Stitched with Love, Undone by Loss

After the Central Park display on June 25, 1988, the future of the NYC Quilt Workshop was uncertain. Originally scheduled to vacate its space at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center by early July, coordinators and volunteers scrambled to keep the effort alive. They succeeded, moving into a makeshift basement room—a former meat locker, marked by a lavender line painted on the floor to guide visitors through the Center’s corridors. The workshop continued to buzz with energy through the summer and into the fall, sending 165 additional panels to the NAMES Project for the historic October display on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Yet sustaining this momentum was not easy. Many of the workshop’s leaders and volunteers were themselves living with HIV or AIDS. Their absence over time was not a matter of fatigue, but of death. Michael Callen, speaking at the Quilt dedication in Central Park, gave words to this reality: “Our bravest and best are falling all around us. Business-as-usual bureaucracy chugs on while we die.”¹

The losses struck close to home. In December 1988, only weeks after the Quilt’s Washington display, the New York Workshop closed its doors for good. That same month, co-organizer Wes Cronk died. His obituary did not mention his work with the Quilt, but the date—December 1, 1988, the first official World AIDS Day—gave his passing an added resonance.² Cronk had been the heart of the workshop, working steadily even as his health declined. His death symbolized both the scale of the epidemic and the urgency of preserving memory through acts of collective care.

In response, volunteers stitched a memorial block in his honor.³ Titled A Guiding Light, it included a poem written by Cronk, a line from the song You’ll Never Walk Alone, and the image of a sewing machine, still in motion. The block became more than a tribute to one man. It stood as a testament to the Workshop itself, and to the community that refused to let memory fade.

James Burke, Cronk’s co-coordinator, carried that spirit forward. A meticulous record-keeper, Burke saved letters, schedules, permits, and ephemera from the Workshop. His papers, now preserved at the LGBT Community Center Archive, are among the most detailed records of New York’s Quilt effort. Thanks to Burke’s dedication, we can reconstruct not only the day of the Central Park display but also the life of the Workshop itself. Together, his archive and the surviving panels remind us that the Quilt was never only about fabric. It was about people—about love, loss, and the act of remembering together.

Notes

Gay Cable Network, Central Park Rally, 6/25/1988, video recording, 1988, Gay Cable Network Archives, MSS.231, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University, https://hdl.handle.net/2333.1/dbrv1hv4.

Obituary clipping for Wes Cronk, December 1, 1988, James Burke Papers, 1970–1996, Collection 44, LGBT Community Center National History Archive, processed January 30, 1996.

Quilt panels for Wes Cronk, 1988–1989, National AIDS Memorial, Block #1251 (01–08), AIDS Memorial Quilt, accessed April 23, 2025, https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

Share Your Story

Your voice matters. If you have memories, photographs, or reflections connected to the AIDS crisis in New York City, we invite you to share them. Together we can preserve these histories and ensure they are never forgotten.