From Silence to Remembrance: The Ongoing Story of HIV/AIDS

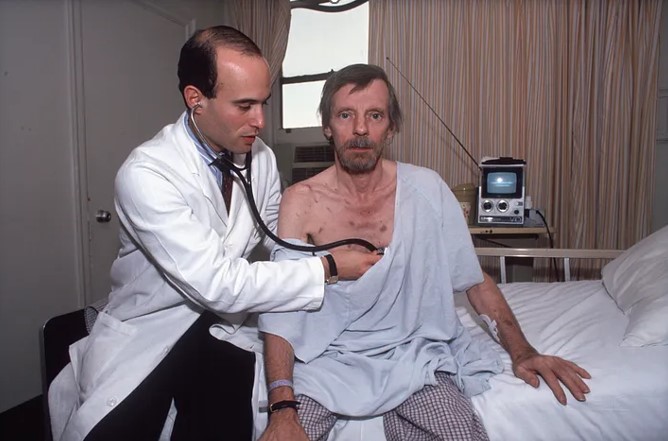

AIDS Patient with Kaposi's Sarcoma, Visible on his Skin, is Examined by Doctor Markowitz. St Clare's Hospital, New York, New York, December 10, 1986. Allan Tannenbaum, Getty Images.

This image reflects how AIDS was first “seen” by the public. Beyond documenting illness, such photographs have become part of how the epidemic is remembered, reminders of both stigma and the dignity of lives that must not be forgotten.

About A Patchwork of Memory

New York City was the epicenter of the AIDS crisis. In the early 1980s, more than half of the nation’s first recorded AIDS cases were here.¹ Hospitals overflowed, funerals became routine, and entire communities—gay men, transgender people, people of color, immigrants, sex workers, and the unhoused—were devastated. Families of choice stepped in where institutions failed, caring for the sick and mourning the dead. Government inaction, media neglect, and stigma compounded the crisis, sending a cruel message that some lives were expendable.²

By the late 1980s, the epidemic had spread nationwide, but New York continued to carry a staggering share of the loss. Tens of thousands of New Yorkers had died by 1990, leaving scars on families and communities and reshaping the city’s neighborhoods and institutions. Christopher Street, Central Park, local churches, and Hart Island, the city’s potter’s field, became landscapes of grief and remembrance.³ These sites are not simply backdrops; they are historic places where mourning, protest, and visibility reconfigured the very meaning of public space.

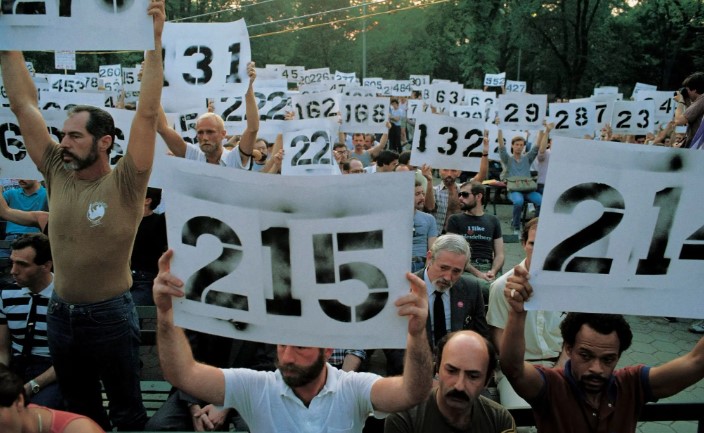

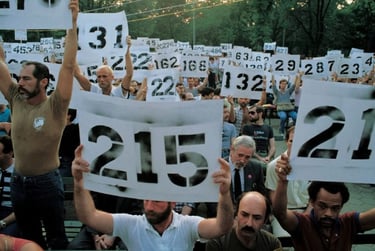

People held signs bearing the number of New Yorkers who had died of AIDS during a demonstration at the Naumburg Bandshell in Central Park, June 1983. By that spring, at least 589 New Yorkers had already died, with hundreds more diagnosed and hospitals struggling to keep pace. Photograph: Alon Reininger/Contact Press Images

These practices of mourning drew on the legacies of the 1970s, when LGBTQ+ New Yorkers claimed visibility through Pride marches, grassroots health initiatives, and liberationist politics.⁴ When AIDS struck, those traditions were reconfigured. Pride parades became both celebrations and funerals. Vigils, protest funerals, and public die-ins confronted political neglect with grief turned outward. ACT UP, founded in 1987, epitomized this transformation by linking mourning with militancy and demanding accountability from the government and the pharmaceutical industries.⁵

Out of this devastation came acts of memory that were as much about resistance as mourning. Candlelight vigils lit up city streets, and protest funerals carried grief into public view. These early efforts were often led by white gay men whose activism, while essential, reflected both their profound loss and their greater access to nonprofit resources, press coverage, and public platforms. Their visibility shaped the way the epidemic was first remembered.

The AIDS Memorial Quilt, when spread across Central Park in 1988, offered a powerful counterbalance. Unlike official monuments or vigils that reflected those with institutional access, the Quilt opened space for a wider range of remembrance. Families, friends, and communities could honor their loved ones directly, creating a collective memorial from personal grief and care. In New York, the Quilt reflected the city’s diversity, with panels for women, Black and Latino New Yorkers, immigrants, trans people, and the unhoused alongside white gay men.⁶ This inclusivity made the Quilt a democratic act of remembrance, ensuring that voices often excluded from official narratives could not be ignored. Yet outside the Quilt, many of these same communities remained marginalized in public commemoration. Churches consecrated books of remembrance, activists carried names of the dead into Pride marches, and decades later, the New York City AIDS Memorial offered permanence in stone.⁷

Members of the People With AIDS (PWA) movement march in the 1986 Gay Pride Parade in New York City, carrying a banner to assert their presence and demand visibility at a time when many sought to silence or ignore them. June 29, 1986. Barbara Alper, Getty Images, https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/members-of-the-people-with-aids-movement-carry-a-banner-news-photo/564168885.

Princess Diana at Harlem Hospital, 1989: When Princess Diana visited Harlem Hospital’s pediatric AIDS ward, she embraced children—many of them Black and Latino, born into poverty, and stigmatized as the epidemic’s most invisible victims. While much of AIDS memorialization has centered on white gay men and downtown activism, Harlem Hospital tells another story: of children, of women who were intravenous drug users, of communities of color bearing a disproportionate burden. Diana’s visit was noteworthy not only for breaking the fear of touch but also for momentarily bringing global attention to those most often left out of remembrance. Photo by Sherlock Robinson. https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com/the-fab-princess-di-visits-harlem-hospital-ny-1989/

The story of AIDS memorialization in New York is both inspiring and fragile. Much of it survives only in scattered newspaper reports, ephemeral posters, photographs, and the recollections of those who lived through it. Without deliberate preservation, these fragments risk being lost. Linking them to place—Christopher Park, Sheridan Square, the Hudson River piers, St. Veronica’s Church, Hart Island—anchors fragile memory in the city’s material and cultural geography. It shows that these are not only sites of loss but also historic sites where communities resisted erasure and reshaped civic life.

Who built the memorials also matters. The Quilt emerged from grassroots work but grew into a national archive. The New York City AIDS Memorial was spearheaded by preservationists and activists who had access to fundraising and design networks, demonstrating how official commemoration often reflects the voices of those with resources and institutional power.⁸ These dynamics raise enduring questions: Whose grief is granted permanence in stone, and whose remains ephemeral, at risk of being forgotten?

A Patchwork of Memory is designed to answer those questions. By tracing the evolution of AIDS memorialization in New York City—from vigils and ephemeral acts to permanent monuments—it restores visibility to those whose grief, activism, and artistry transformed the city. This project complements the mission of historic sites work by documenting how urban spaces became layered memorial landscapes, where the struggles of marginalized communities left marks that demand preservation. To remember AIDS is not only to honor the dead. It is to recognize these sites as historic ground, and to continue the struggle for justice, recognition, and care.⁹

Footnotes

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, HIV/AIDS Annual Surveillance Statistics, 2013 (New York: NYC DOHMH, 2014).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report (Atlanta: CDC, 1988).

Daniel C. Brouwer and Charles E. Morris III, “Decentering Whiteness in AIDS Memory: Indigent Rhetorical Criticism and the Dead of Hart Island,” Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 5, no. 1 (2012): 1–23.

Katie Batza, Before AIDS: Gay Health Politics in the 1970s (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018).

Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” in AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism, ed. Douglas Crimp (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1988), 3–18.

Eric Nagourney, “Quilt Unfolds Painful Story of AIDS,” New York Times, June 20, 1988; Cleve Jones, Stitching a Revolution: The Making of an Activist (San Francisco: Harper, 2000).

Marita Sturken, Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

New York City AIDS Memorial, “About,” https://www.nycaidsmemorial.org.

Jeffrey Schmalz, “Whatever Happened to AIDS?” New York Times Magazine, December 6, 1993.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled, 1991, Third Avenue and East 137th Street, Bronx, New York. One of 24, displayed across New York City. The image of an unmade bed with two pillows marked by the depressions of absent heads became a quiet but powerful memorial during the AIDS crisis. At once intimate and universal, the work speaks to love, loss, and the everyday spaces left empty by the epidemic. By placing a symbol of private mourning in the public sphere, Gonzalez-Torres invited collective remembrance, showing how AIDS memorialization could exist not only in monuments but in the fabric of the city itself. Photo: Peter Muscato, The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation.

The Crisis Continues

This project is about memorialization—but it is also a reminder that AIDS is not over. Even as we honor the vigils, Quilt panels, Pride marches, and monuments that emerged in New York City, the epidemic persists. Today, 40.8 million people worldwide live with HIV, and in 2023, there were 1.3 million new infections and 630,000 AIDS-related deaths.¹ In the United States, more than 1.2 million people are living with HIV, with 31,800 new infections recorded in 2022.²

These numbers, however, tell only part of the story. While many now have access to life-saving treatment, inequities remain stark. Black and Latino communities, transgender women, people who use drugs, and those living in poverty continue to face higher rates of infection and barriers to care.³ Stigma and discrimination, within healthcare systems, institutions, and society, compound these inequities, leaving the most marginalized to shoulder the heaviest burdens.

To remember AIDS, then, is not only to look back. It is to confront how grief, inequality, and stigma still shape the present, and to carry forward the demand for care, justice, and dignity into the future.

Notes

UNAIDS, “Fact Sheet: Global HIV & AIDS Statistics — 2024,” Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet.

HIV.gov, “U.S. Statistics,” Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “HIV and African American People,” HIV by Group, last reviewed February 5, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/index.html.