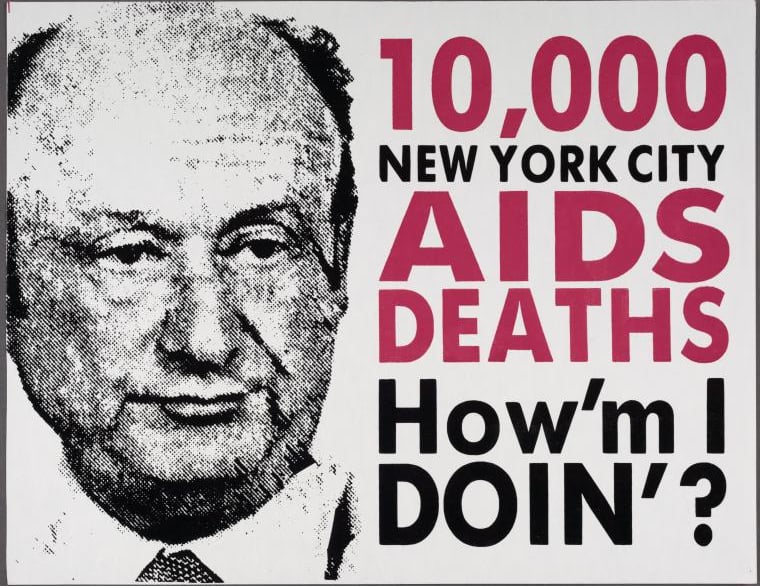

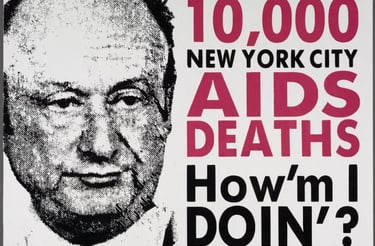

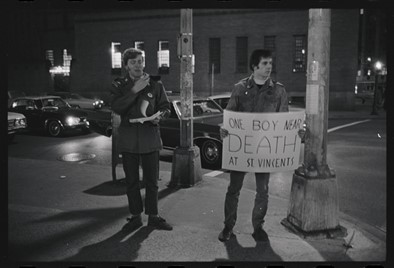

Tom Doerr (left) and Marty Robinson (right), Participants in the Stonewall Uprising and Members of the Gay Activist Alliance (GAA), at the Snake Pit Vigil, March 8, 1970. Diana Davies. NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/the-snake-pit/

Grief in the Streets: Candlelight Vigils and the Birth of AIDS Memorial Culture

In the early years of the AIDS epidemic, when hospitals, churches, and political leaders turned away, queer communities created their own rituals of mourning. The candlelight vigil, simple, portable, and profoundly symbolic, emerged as one of the earliest and most powerful responses to loss. These gatherings transformed sidewalks, parks, and church steps into sacred sites of visibility and protest. They were at once spiritual ceremonies and political statements: moments when candles, voices, and bodies in the street defied erasure and demanded recognition.

Candlelight vigils did not appear suddenly in the 1980s. They drew on the legacies of post-Stonewall activism in the 1970s, when queer New Yorkers had already used silent marches and candlelit processions to mourn violence and resist repression. In the AIDS era, these traditions evolved into urgent acts of communal survival. Vigils gave shape to what scholars call “disenfranchised grief”—mourning denied by dominant culture—and turned it into collective resistance. Partners barred from hospital bedsides, families silenced by stigma, and communities excluded from official rituals could gather publicly, name their dead, and be seen.

Often dismissed at the time as too quiet or symbolic, vigils carried deep political weight. They provided the emotional foundation for later, more confrontational activism, from ACT UP’s political funerals and die-ins to the creation of the NAMES Project Quilt and, eventually, permanent monuments like the New York City AIDS Memorial. Each candlelit gathering, though fleeting, was a vernacular memorial, a low-tech architecture of remembrance built from flames, signs, and voices. As the candles burned down, they embodied both the fragility of life and the endurance of community.

The practice of candlelight vigils in queer New York emerged out of both necessity and inheritance. In the decades before the AIDS epidemic, LGBTQ+ communities endured violence, police raids, and widespread indifference from civic and religious institutions. Denied traditional avenues of mourning, they created their own rituals of remembrance and resistance in the streets. The candlelight vigil—long rooted in religious and cultural traditions—proved especially powerful: its quiet glow transformed ordinary sidewalks into sacred stages for grief and defiance.

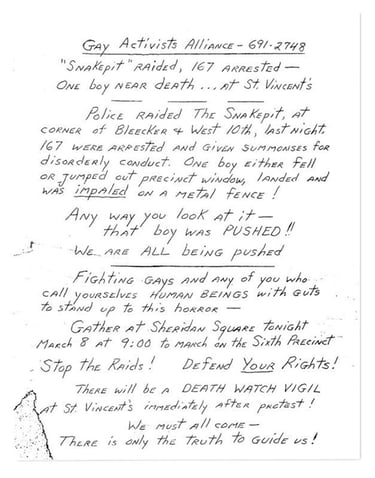

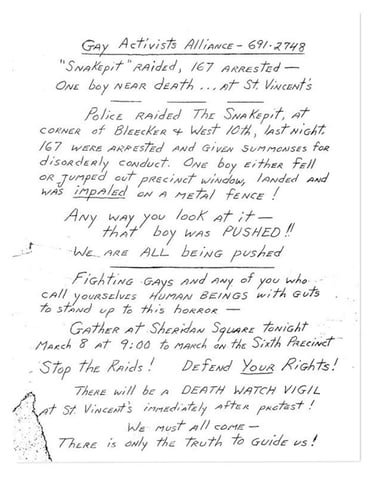

These practices began to crystallize in the early 1970s, following the Stonewall uprising. When police raided the Snake Pit bar in March 1970, injuring Argentine immigrant Diego Viñales, hundreds of New Yorkers gathered in Sheridan Square. Leaders of the newly formed Gay Activists Alliance, including Jim Owles, helped channel the anger and grief into collective action. The crowd marched by candlelight to St. Vincent’s Hospital in an act of solidarity and outrage.¹ The procession illuminated the streets of the Village, blending grief with militant resistance, and demonstrated how public mourning could be transformed into political action. This early vigil foreshadowed the forms of protest and remembrance that would become central during the AIDS crisis a decade later.

Eight years later, the assassination of Harvey Milk on November 27, 1978, catalyzed another major wave of candlelight mourning. That night, 40,000 people in San Francisco held candles as they silently marched from the Castro to City Hall in one of the largest public vigils in U.S. history. Randy Shilts described the scene vividly: “The tens of thousands of candles glimmered in the night … so that from a distance it appeared that a thousand stars had fallen onto the avenue and were moving slowly toward City Hall.”² In New York, despite heavy rain, approximately 250 people gathered at Sheridan Square and processed by candlelight to the Metropolitan Duane Methodist Church. Village Voice reporter Barry Walters noted how grief shifted into defiance, as participants shouted, “Enough shit!” in frustration at systemic neglect and homophobia. Many of the same activists who had rallied after the Snake Pit raid—such as Gay Activists Alliance leader Jim Owles and bookstore owner Craig Rodwell—were present, underscoring continuity across the decade.³

The assassination’s aftermath further intensified public grief. In May 1979, Dan White received a lenient sentence of voluntary manslaughter for the killings of Milk and Mayor George Moscone. Outrage spread across the country. In San Francisco, the “White Night Riots” erupted. In New York, activists staged their own protests. Jim Hubbard, who would later chronicle AIDS activism in his films, documented sit-ins near Christopher Park and candlelit marches through Sheridan Square. These actions disrupted traffic, blocked intersections, and transformed public mourning into a visible confrontation with state power.⁴ Hubbard later reflected that the Milk assassination and its aftermath laid the groundwork for the strategies of militant grief that would define AIDS-era protests—where candles, silence, and disruption fused into a powerful visual and emotional language.

Associated Press, More than 25,000 persons jammed the park and streets around San Francisco’s City Hall on Monday, Nov. 28, 1978. NPR, November 27, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/11/27/670657965/40-years-after-the-assassination-of-harvey-milk-lgbt-candidates-find-success

Two years later, in November 1980, that language was again invoked after the “West Street Massacre,” when gunman Ronald Crumpley opened fire outside the Ramrod bar, killing two men and injuring several others. More than 2,000 mourners assembled in the West Village and marched by candlelight to the piers. A bugler played taps and a 24-piece band performed “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” underscoring how vigil space functioned as both mourning ground and protest stage.⁵

Together, these early vigils established a repertoire of queer public mourning in New York City. They fused grief with activism, solidarity with defiance, and private loss with collective visibility. When AIDS struck in the early 1980s, queer New Yorkers already possessed this ritual vocabulary. The epidemic did not invent the candlelight vigil, but it amplified and transformed it—turning a practice born of resistance into one of the defining symbols of queer memorialization.

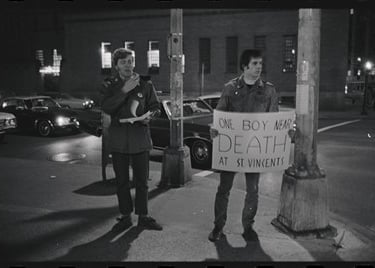

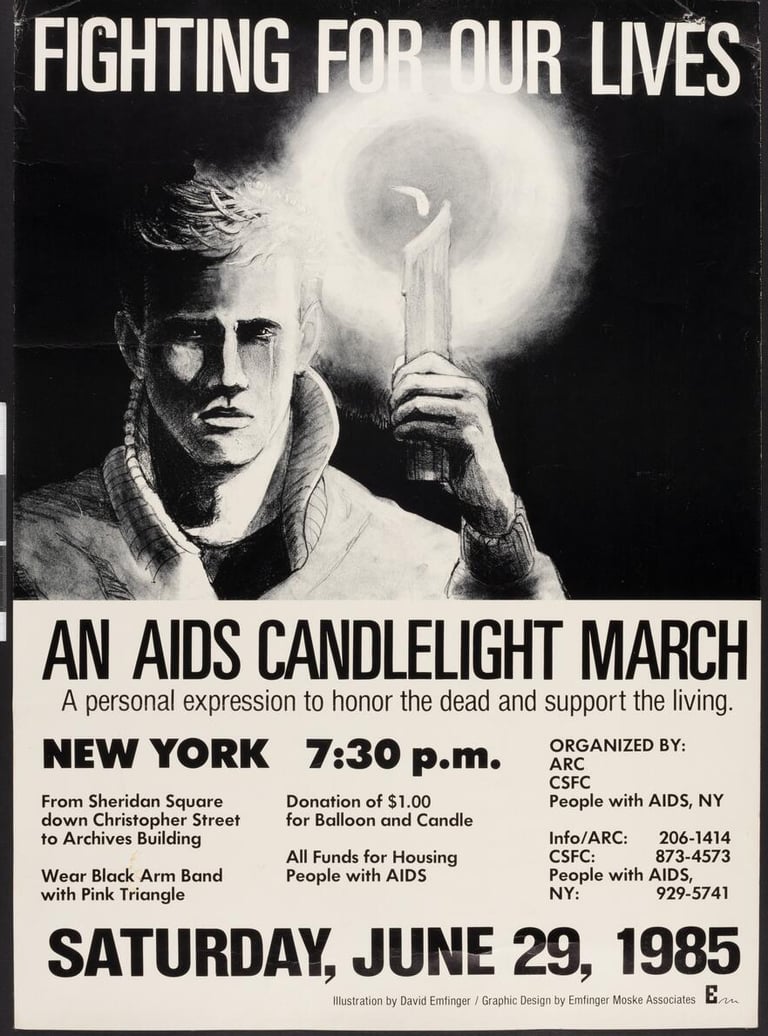

The Ramrod, Greenwich Village, 1980

Once a thriving leather bar on West Street, the Ramrod closed after a deadly anti-gay shooting on November 28, 1980. A candlelight vigil followed, an act of mourning that foreshadowed the public rituals of grief and resistance that would define the AIDS crisis—announced just weeks later in the New York Times. Photo by Harvey Wang. The Museum of the City of New York.

Gay Activist Alliance flyer for the Snake Pit raid protest, March 1970. LGBT Historic Sites Project, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/the-snake-pit/

Notes:

NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, “The Snake Pit,” accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/the-snake-pit/.

Randy Shilts, The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1982), 285–86.

Les Ledbetter, "San Francisco Tense as Violence Follows Murder Trial," New York Times, May 23, 1979. https://www.nytimes.com/1979/05/23/archives/san-francisco-tense-as-violence-follows-murder-trial-more-than-140.html; Barry Walters, “Harvey Milk Memorial in New York,” Village Voice, December 4, 1978.

Jim Hubbard, commentary on May 21–22, 1979, accessed April 19, 2025, https://www.jimhubbardfilms.com/films/may-21-22-1979.

Andy Humm, quoted in David Dunlap, “2 Slain in Greenwich Village Attack on Homosexual Bar,” New York Times, November 20, 1980.

The First AIDS Candlelight Vigil in New York City

The tradition of AIDS candlelight vigils began in San Francisco. On May 2, 1983, activists Bobbi Campbell, Bobby Reynolds, Dan Turner, and Mark Feldman organized Fighting for Our Lives, a memorial sponsored by the Kaposi’s Sarcoma Research and Education Foundation. Thousands filled Market Street in silence, carrying candles and photographs of those already lost. Local press described “solemn, silent throngs,” underscoring a mood of mourning and compassion.¹ The vigil was among the first large-scale acts of AIDS remembrance in the United States, linking grief with visibility and setting a model that would spread across the country.

That same evening, New York City staged its first AIDS candlelight vigil, and the tone could not have been more different. Beginning at Sheridan Square, already consecrated ground of queer resistance since Stonewall, nearly 5,000 mourners gathered to honor the 520 people who had died of AIDS.² From the West Village, participants carried candles down Bleecker Street to the Federal Building at 26 Federal Plaza, confronting government offices with the reality of loss.

New Yorkers infused the vigil with defiance. Marchers wore black armbands marked with pink triangles, once a Nazi emblem of persecution and now a reclaimed symbol of queer resistance. Homemade banners declared, “Politics is an opportunistic disease” and “Man: The next endangered species.” The quiet glow of candlelight was punctuated by chants: “Money for AIDS now!” and “Ronald Reagan, he’s no good, send him back to Hollywood!”³

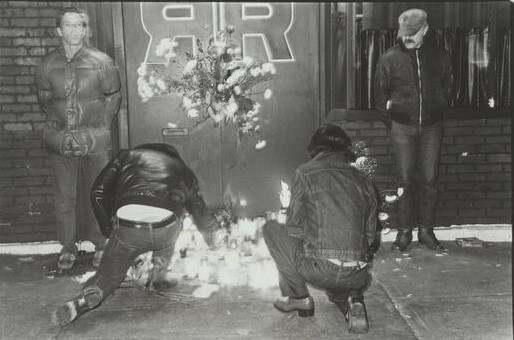

David Emfinger, Fighting For Our Lives: An AIDS Candlelight March, 1983.

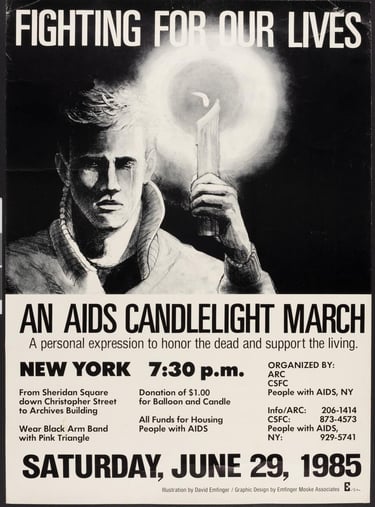

One of the most iconic artifacts of this era is the 1985 Fighting for Our Lives vigil poster, illustrated by artist David Emfinger. Rendered in stark black and white, it depicts a young white man in a varsity jacket, solemn-faced, with a single tear down his cheek, holding a candle aloft like a torch. The image is at once vulnerable and defiant, its minimalist aesthetic amplifying the urgency of the moment.

The text beneath the illustration outlines simultaneous march routes for San Francisco (from the Castro to UN Plaza) and New York (from Sheridan Square to the Federal Building). Participants were instructed to wear armbands with pink triangles and to bring candles, fusing visual symbols of queer resistance with the ritual of mourning. The inclusion of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) hotline grounds the poster in the practical realities of care, linking the act of public memorialization with the infrastructures of service and survival built by the community itself.

ClampArt, June 2017. https://clampart.com/2017/06/an-aids-candlelight-march/

Rich Wandell, AIDS Candlelight March, New York City, May 2, 1983. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-7531-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

At Federal Plaza, Jim Fouratt introduced Larry Kramer, whose words electrified the crowd: “AIDS is our Vietnam. Our government has produced nothing but lethargy and lies. We are dying here, not in El Salvador.” Kramer denounced the NIH’s paltry $245,000 budget for AIDS research as “a piss-poor sum,” drawing boos as he condemned Reagan and Mayor Ed Koch.⁴ What began at Sheridan Square as remembrance ended as indictment, turning mourning into protest.

The contrast between San Francisco’s mournful procession and New York’s militant march reveals two faces of the same new ritual. In San Francisco, the vigil emphasized grief and healing; in New York, it transformed mourning into confrontation. Together, they marked the birth of AIDS vigil culture—one of the most enduring and powerful forms of queer memorialization.

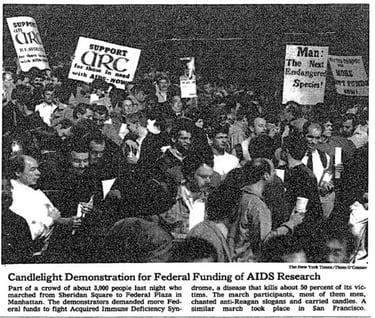

Thom O’Connor, The AIDS Candlelight Vigil, mourners hold candles and carry signs that read, Support ARC Research and Man: The Next Endangered Species, New York Times, May 3, 1983, 32. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1983/05/03/issue.html

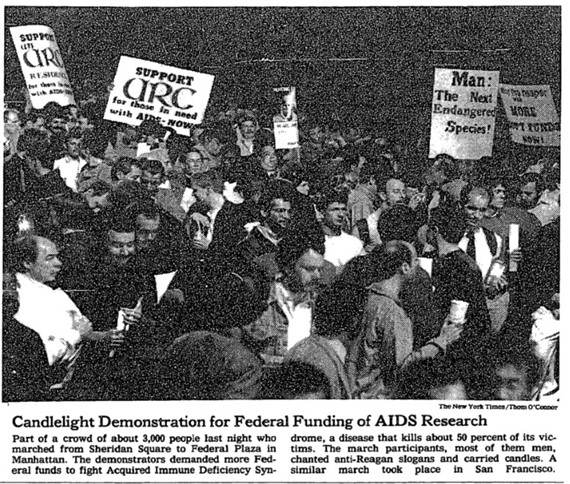

Yet the power of New York’s march was erased mainly in mainstream coverage. While Gay Community News captured the full scope of the event, The New York Times buried a small photograph and caption on page 32, estimated the crowd at 3,000, and framed the vigil narrowly as a plea for research funding.⁵ This erasure not only diminished the political urgency of the moment, but also shaped how early queer grief would be remembered, or forgotten, in public memory.

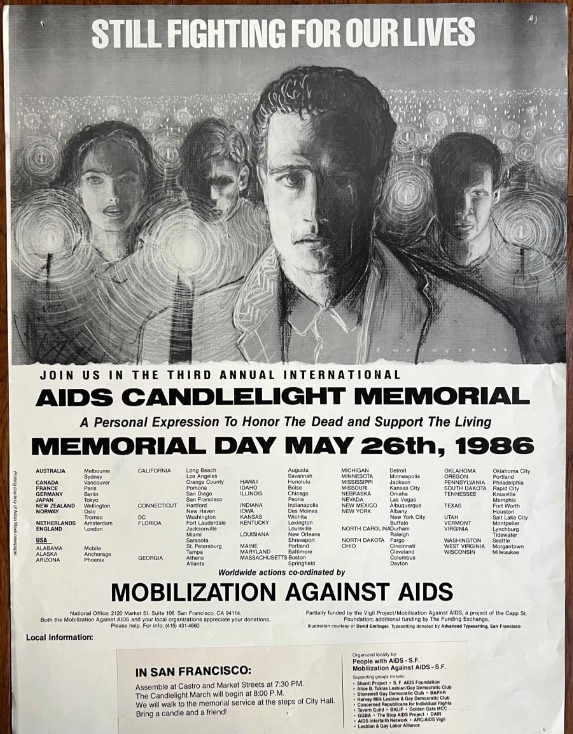

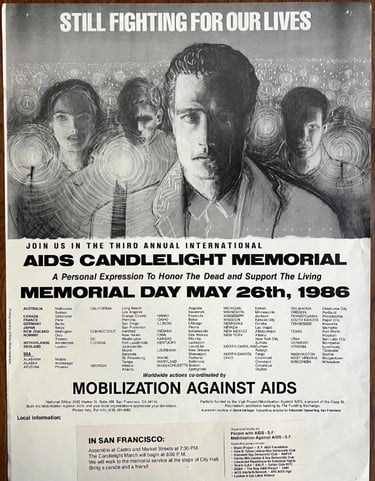

Still Fighting for Our Lives poster, 1986. This redesign marked a turning point in the visual language of AIDS activism. The solitary white male figure of earlier posters was replaced by four diverse individuals—different races, genders, and presentations—standing shoulder to shoulder before a sea of candle flames. The black background gave way to muted gray, shifting the tone from stark mourning to collective endurance. The central slogan, “Still Fighting for Our Lives,” underscored both the escalating toll of the epidemic and the persistence of resistance.

By widening representation, the poster acknowledged the diverse communities impacted by AIDS while retaining the candle as its unifying symbol. The image carried memory through print and protest, linking the ephemeral act of marching to a broader history of solidarity, grief, and defiance

David Emfinger, Still Fighting For Our Lives, 1986. Dark Entries Records. https://www.darkentriesrecords.com/store/the-magazine/fighting-for-our-lives/

Notes

¹ C.W. Nevius, “Candlelight Memorial Recalls Early Days of AIDS Epidemic,” SFGate, May 1, 2008; Kevin Fagan, “Candlelight Memorials Grew out of S.F. AIDS Vigil,” SFGate, May 17, 2011.

² Rich Wandell, AIDS Candlelight March, New York City, May 2, 1983, New York Public Library Digital Collections.

³ Ibid.

⁴ Nelson, “Thousands Demand More AIDS Funding.”

⁵ “Candlelight Demonstration for Federal Funding of AIDS Research,” New York Times, May 3, 1983, 32.

The 1983 Central Park Vigil: From Private Grief to Public Reckoning

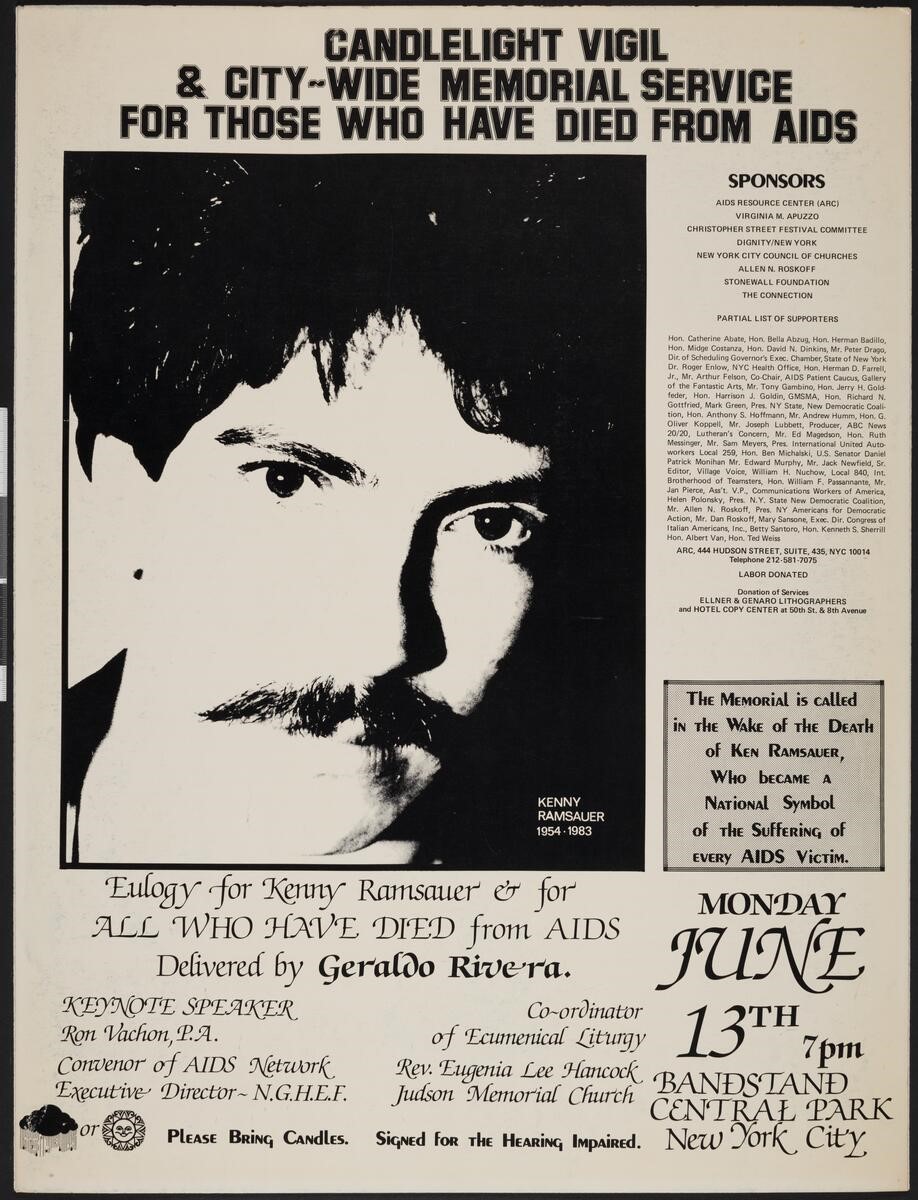

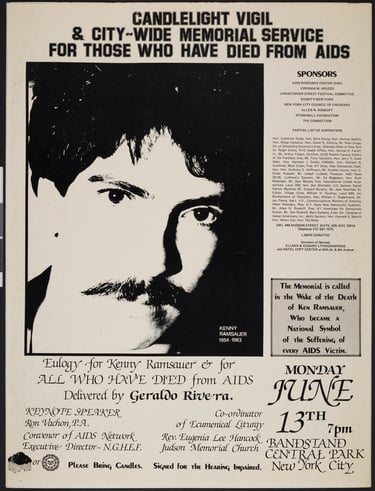

On June 13, 1983, more than 1,500 people gathered at the Naumburg Bandshell in Central Park to remember Ken Ramsauer, a 27-year-old lighting designer who had died of an AIDS-related illness just weeks earlier.¹ Ramsauer’s name was already known to millions of Americans. Days before his death, he appeared in a nationally televised segment of ABC’s 20/20, where journalist Geraldo Rivera introduced him as “the most frightening medical mystery of our time.”² The images were stark: Ramsauer, his face swollen by Kaposi’s sarcoma, slumped in a wheelchair, recounted how hospital staff had mocked him as “the faggot in 208.”³ For some, the broadcast humanized the epidemic; for others, it sensationalized suffering. Either way, Ramsauer became, as The New York Times noted, “a national symbol of the discrimination and pain suffered by victims of a condition that ravages the body’s immune system.”⁴

The Central Park vigil, held at the Naumburg Bandshell and organized by the AIDS Resource Center alongside other community groups, was announced as a “Citywide Memorial Service for Those Who Have Died of AIDS.” Transforming one of New York’s most visible public stages into a site of mourning, the poster for the event listed not only LGBTQ+ organizations but also political and religious leaders, including Bella Abzug, David Dinkins, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and Mayor Ed Koch.⁵ By convening at the heart of Central Park, a civic gathering place long associated with cultural expression and public assembly, the vigil made clear that AIDS could no longer be relegated to the shadows.

Unknown, Poster for Candlelight Vigil and Citywide Memorial Service for Those Who Have Died of AIDS, 1983. At its center was a high-contrast photograph of Ken Ramsauer in healthier days, resisting the prevailing media imagery of suffering and affirming his dignity. Its list of sponsors ranged from grassroots groups, such as the Christopher Street Festival Committee and the Stonewall Foundation, to Dignity/NY, as well as prominent figures including Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Bella Abzug, and David Dinkins. The AIDS Memorial Foundation. https://aidsmonument.org/history/

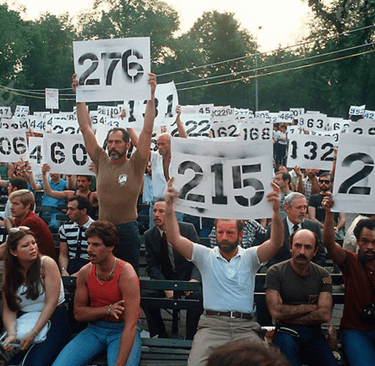

Alon Reininger, Richard Locke Holds the Number 276, New York City, June 1983. New-York Historical Society, “AIDS in New York: The First Five Years.” https://www.nyhistory.org/exhibitions/aids-new-york-first-five-years

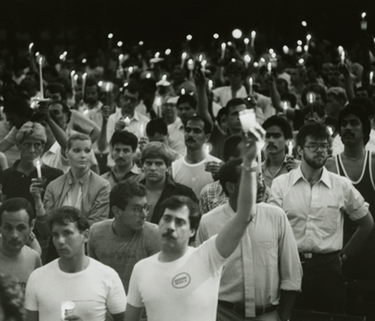

As the sun set, mourners filled the plaza with candlelight. Many carried placards marked with numbers, representing the mounting death toll. Though the official count stood near 600, it was widely acknowledged to be far higher. Photographer Alon Reininger captured Richard Locke, a former gay erotic film star turned activist, holding a sign marked “276.”⁶ Once celebrated for his muscular physique in the culture of 1970s sexual liberation, Locke now embodied another form of strength: public witness to grief. All around him, the quiet act of men holding candles redefined masculinity, insisting that vulnerability itself was a form of resistance.

Journalist David France, present that night, described the harrowing scene: “The plaza was crowded with 1,500 mourners cupping candles against the darkening sky. A dozen men were in wheelchairs, so wasted they looked like caricatures of starvation. I watched one young man twist in pain that was caused, apparently, by the barest gusts of wind around us.”⁷ A friend beside him whispered, “It looks like a horror flick… We had found the plague.”⁸

New-York Historical Society, Central Park Candlelight Vigil, 1983. New York Historical Museum & Library. Accessed May 3, 2025. https://www.amny.com/news/early-years-of-aids-remembered-at-new-york-historical-society/

The vigil also created space for deeply personal acts of remembrance. Julius Genachowski, then a student at Columbia College and editor of the Columbia Daily Spectator, recalled one man, William, standing behind the crowd and whispering the name of his lover, “Bill Christopher.” Realizing no one could hear, William shouted the name aloud and then wept. “It was not the uncontrollable sobbing of one who has lost everything,” Genachowski later wrote, “but the soft whimper of one who knows more deaths lie ahead.”⁹ His act of naming: private grief breaking into public speech, captured the vigil’s essence: resisting silence, refusing erasure, and remembering those the world preferred to forget.

Public officials offered prayers, pledged to fight discrimination, and condemned funeral homes that refused to handle the bodies of people with AIDS.¹⁰ For many activists, however, these gestures rang hollow, given the city’s refusal to adequately fund services or respond to urgent community needs. Still, the vigil forced the epidemic into view. What began as a memorial for Ramsauer became New York City’s first large-scale AIDS vigil, an event that redefined mourning as a form of political reckoning.

Notes

Lindsey Gruson, “1,500 Attend Central Park Memorial Service for AIDS Victim,” New York Times, June 14, 1983, sec. B, 4, https://www.nytimes.com/1983/06/14/nyregion/1500-attend-central-park-memorial-service-for-aids-victim.html.

Geraldo Rivera, 20/20, ABC News, May 1983, quoted in David France, How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS (New York: Knopf, 2016), 37.

France, How to Survive a Plague, 37.

Gruson, “1,500 Attend Central Park Memorial Service.”

Julius Genachowski, “1500 Mourn Deaths of Those with AIDS,” Columbia Daily Spectator, June 22, 1983, https://spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu/cgi-bin/columbia?a=d&d=cs19830622-01.2.5.

Alon Reininger, Richard Locke Holds the Number 276, New York City, June 1983, New-York Historical Society, “AIDS in New York: The First Five Years,” accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.nyhistory.org/exhibitions/aids-new-york-first-five-years.

David France, How to Survive a Plague, 41.

France, How to Survive a Plague, 42; Larry Kramer, Reports from the Holocaust: The Making of an AIDS Activist (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989), 75–78.

Genachowski, “1500 Mourn Deaths of Those with AIDS.”

Gruson, “1,500 Attend Central Park Memorial Service.”

Where Pride Began: AIDS Vigil and the Legacy of Christopher Street

By the mid-1980s, candlelight vigils had become a defining ritual of New York’s response to AIDS. What began as spontaneous neighborhood gatherings quickly evolved into recurring acts of collective mourning and political defiance. In 1983, activists in San Francisco and New York launched Fighting for Our Lives, which evolved into the International AIDS Candlelight Memorial, observed every third Sunday in May, and is still held around the world today.¹ Yet in New York, vigils took on a distinctive shape, woven into the fabric of Pride Week itself. Mourners and activists gathered not only in Central Park but also along Christopher Street, affirming that grief belonged at the very center of queer visibility.

Frank Fournier, Fighting for Our Lives Vigil, Sheridan Square, New York City, 1985. Hyperallergic, “Five Years When Silence Equaled Death.” https://hyperallergic.com/72787/five-years-when-silence-equaled-death/

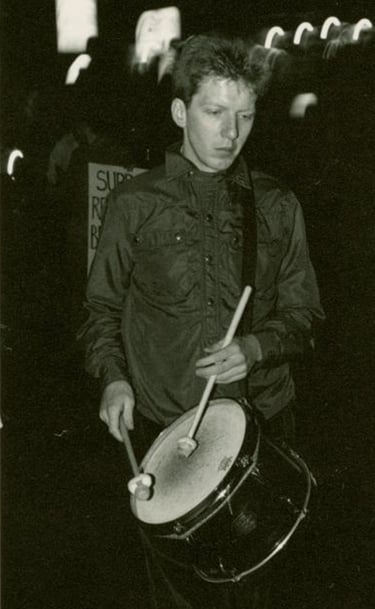

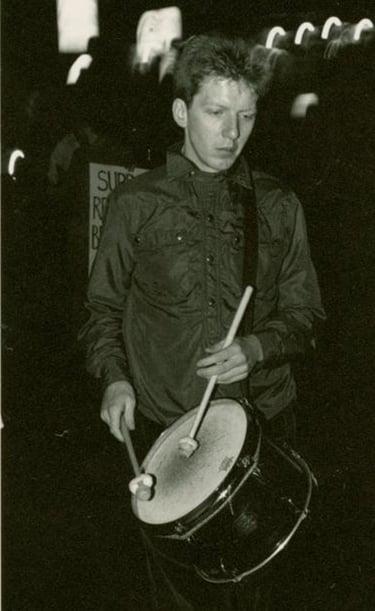

One vigil that did not vanish entirely was held on June 29, 1985. That night, the Christopher Street Festival Committee organized a procession that moved west along Christopher Street and came to rest at St. Veronica’s Church. Hundreds of people gathered in the heavy summer air, carrying candles and placards that read Fighting for Our Lives or simply listed the names of the dead. Balloons inscribed with names were held until the end of the vigil, then released together into the night sky, a fragile but striking gesture of collective remembrance. The Gay Cable News Network filmed the event, capturing mourners lined along Christopher Street while revelers passed on their way to the waterfront festivities that preceded the Pride Parade.³

Andrew Stein’s remarks at the 1985 Christopher Street vigil were striking in their recognition but also revealing in their silences. As Manhattan Borough President, he was one of the first elected officials in New York City to acknowledge AIDS in such a setting publicly. His proclamation established a borough-wide Remembrance Week, signaling that the epidemic deserved civic recognition rather than silence. He praised the work of community organizations, including the Christopher Street Festival Committee, the AIDS Resource Center, and People With AIDS New York, and he urged governments to provide more funding for research, services, and patient care. Perhaps most significant was his mention of the “lovers and families” of people with AIDS. In 1985, when same-sex partners were often excluded from hospital rooms and denied recognition as next of kin, this language marked a rare moment of validation from an official voice.⁴

Yet the speech also reflected the limitations of political discourse in the mid-1980s. Stein identified AIDS as a disease afflicting “America’s gay population.” While this was true in terms of the epidemic’s visibility and impact on gay men, it reinforced the prevailing narrative that AIDS was confined to a single group. Missing from his remarks were the women, people of color, immigrants, sex workers, people who used drugs, and others who were already suffering devastating losses. By framing AIDS in narrowly demographic terms, his words excluded the broader reality of who was affected.

His reliance on federal statistics —10,000 reported cases and predictions that the number would double within a year —added urgency but also depersonalized the crisis. Numbers conveyed scale, but they rendered the epidemic abstract. For many, however, his words only confirmed years of government neglect already excoriated in Larry Kramer’s essay “1,112 and Counting.”⁵ For those gathered on Christopher Street, who held placards with names and released balloons in memory of friends and lovers, the epidemic was not a statistic but an intimate reality.

Stein’s proclamation, therefore, existed in tension with the vigil itself. On one hand, it offered symbolic recognition from civic leadership at a time when government silence had been the norm. On the other hand, it revealed how constrained that recognition was, framed through narrow demographics, statistics, and abstract appeals for funding. The vigil’s candles, placards, and balloons conveyed a fuller truth than the proclamation could hold, demonstrating how community acts of remembrance often carried more resonance than official words.

Archival footage from the Gay Cable News Network (GCN) captures the vigil in stark detail: rows of mourners holding candles, hymns echoing down Christopher Street, faces lit by grief and defiance. The next day, the same block erupted with the Christopher Street Festival, with music, banners, and dancing in the rain following the Lesbian and Gay Pride Parade. Together, the vigil, the parade, and the festival revealed the dual rhythm of queer life under AIDS: mourning and militancy one night, visibility and survival the next.

Jim Hubbard, Candlelight Vigil, Christopher Street, New York, 1988, Screenshot of Crowd Holding Candles and Carrying Balloons. Unedited footage. https://www.jimhubbardfilms.com/unedited-footage/candlelight-vigil-christopher-street-new-york-c-1988

By May 1988, this pattern of remembrance had solidified. That spring, the Christopher Street Festival Committee again organized a candlelight procession, beginning in Christopher Park, the small triangular space across from the Stonewall Inn that had already become a symbolic stage for queer memory. Volunteers decorated the park’s iron fences with wreaths and flowers, while white balloons were passed through the crowd for participants to inscribe with the names of their loved ones who had passed away. From there, the march wound slowly down Christopher Street, the very artery that had carried demonstrators during the Stonewall uprising two decades earlier, before turning west toward the Hudson River.

Jim Hubbard, Candlelight Vigil, Christopher Street, New York, 1988, Screenshot of the Empire City Motorcycle Club. Unedited footage. https://www.jimhubbardfilms.com/unedited-footage/candlelight-vigil-christopher-street-new-york-c-1988

Filmmaker Jim Hubbard recorded the vigil on hand-processed 16mm film, ensuring the event would not pass into silence.⁶ His footage captures the procession in striking detail. At the front rode the Empire City Motorcycle Club, their headlights cutting through the evening darkness. Usually a symbol of power and masculine bravado, their slow, deliberate movement reframed the motorcycle as an emblem of vulnerability and collective strength. Behind them marched the Lesbian & Gay Big Apple Corps, their instruments carrying the steady cadence of a funeral procession. The transformation of a marching band, an icon of parades and Americana, into a vehicle of queer mourning was itself an act of cultural subversion, a reclamation of national ritual for a community still excluded from its promises.

Behind them flowed thousands of mourners carrying candles, Quilt panels, and placards inscribed with names. Hubbard’s lens reveals not only the diversity of the crowd but the presence of well-known figures: the Christopher Street Festival Committee itself; veteran activist Ed Murphy, once a bouncer at the Stonewall Inn; and members of ACT UP, including Jamie Leo, Gerri Wells, Ilith Rosenblum, Michael Nesline, and David Robinson.⁷ Their presence marked a shift: grief was no longer only private or solemn, but also openly political. ACT UP’s contingent embodied a different energy: anger and defiance braided into mourning, transforming the vigil into a bridge between memory and militant activism.

The 1988 procession culminated at St. Veronica’s Church, a parish that by then had become one of Manhattan’s few Catholic sanctuaries for people with AIDS. On its steps, prayers were spoken, speeches delivered, and the Jewish Kaddish recited, blending religious ritual with political protest. The sight of candles flickering across the church façade fused sacred tradition with the urgency of queer survival. Finally, mourners carried their grief westward, moving to the Hudson River. There, balloons were released into the night sky, and flowers and candles were set adrift on the water. The flames floated outward—some extinguished quickly, others drifting beyond sight—an ephemeral but powerful gesture that echoed earlier vernacular memorials while asserting the persistence of memory.

This 1988 vigil crystallized the evolution of AIDS memorialization in New York. Where the 1983 march had sought legitimacy in the civic space of Federal Hall, and the 1985 vigil anchored remembrance in the heart of the Village, the Christopher Street procession of 1988 blended both trajectories. It rooted grief in queer geography while demanding public recognition. It was both ritual and protest, silence and defiance, a community declaring that its dead would not be forgotten and that its grief itself was political.

Notes

“International AIDS Candlelight Memorial,” Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+), accessed February 2025, https://gnpplus.net/our-work/international-aids-candlelight-memorial/.

Gay Cable Network, Pride and AIDS Vigil Coverage, June 29–30, 1985, GCN Collection, Fales Library & Special Collections, New York University, https://findingaids.library.nyu.edu/fales/mss_231/contents/aspace_ref3571/.

Frank Fournier, Fighting for Our Lives Vigil, New York City, 1985. Hyperallergic, “Five Years When Silence Equaled Death.” https://hyperallergic.com/72787/five-years-when-silence-equaled-death/

Gay Cable Network, Pride and AIDS Vigil Coverage, June 29–30, 1985

“Larry Kramer, “1,112 and Counting,” New York Native, March 14–27, 1983.

Jim Hubbard, Candlelight Vigil, Christopher Street, New York, c. 1988, unedited footage, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.jimhubbardfilms.com/unedited-footage/candlelight-vigil-christopher-street-new-york-c-1988.

Hubbard, Candlelight Vigil, Christopher Street,

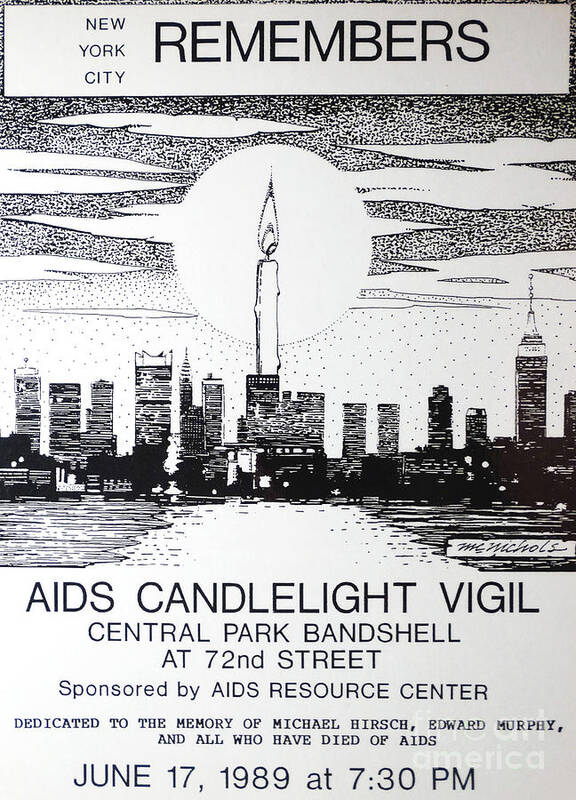

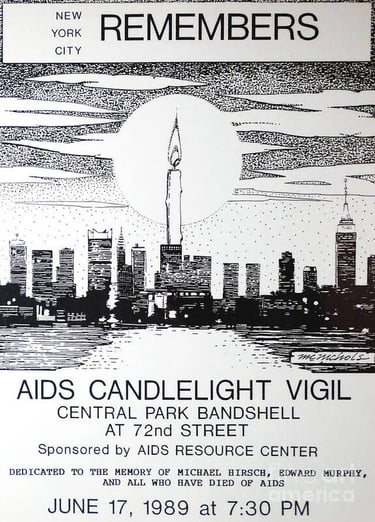

Vigils often took place in Central Park. William Hart McNichols designed this 1989 graphic for the AIDS Candlelight Vigil held at the Naumburg Bandshell. The event was dedicated to Michael Hirsch, founder of Body Positive of New York, an AIDS support group; Edward Murphy, a gay-rights leader and founder of the Christopher Street Festival; and all who have died of AIDS. https://frbillmcnichols-sacredimages.com/featured/nyc-aids-poster-william-hart-mcnichols.html?product=art-print

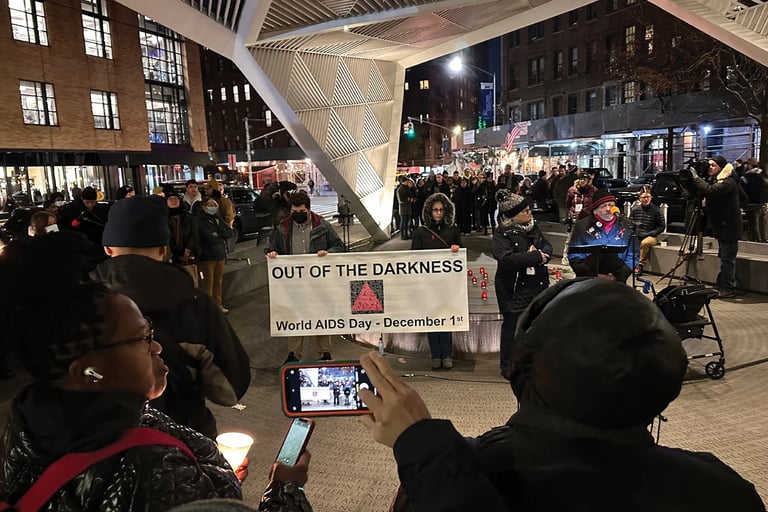

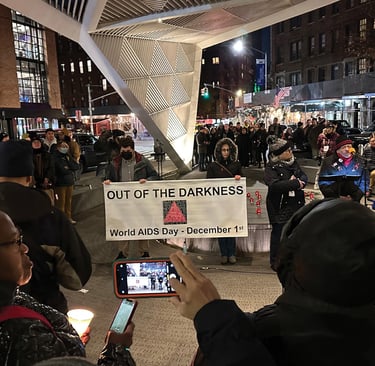

Participants of the Gay Men's Health Crisis (GMHC)-sponsored Out of the Darkness vigil gather at the NYC AIDS Memorial on World AIDS Day, December 1, 2022. https://gmhc.org/wad-2022-photos/

Vigils Today in New York City

The tradition of candlelight vigils in New York continues today, now anchored by institutions that link grassroots memory with formal commemoration. Each year on World AIDS Day, the New York City AIDS Memorial hosts a vigil in partnership with Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) and community allies. At the Memorial, participants gather with candles before processing through the West Village to St. John’s Lutheran Church, where the names of those lost are read aloud.¹ GMHC frames the event as both remembrance and renewal, balancing mourning with performance, art, and public testimony.

New York City Health + Hospitals also plays a central role in sustaining this ritual. In Brooklyn, NYC Health + Hospitals/Woodhull has hosted vigils marking World AIDS Day, bringing together patients, health care workers, and community members.² The hospital has a deep connection to the epidemic, having become the first facility in the city’s public system to be designated an AIDS center in 1993. These vigils underscore how public hospitals—once sites of fear and stigma—are now also places of remembrance and resilience.

Together, these institutions carry forward a tradition that began with the ephemeral marches and vigils of the 1980s. What was once fragile and improvised has become an established part of the city’s commemorative landscape. Today’s vigils affirm continuity with the past: remembrance remains both a ritual of grief and a declaration of survival, sustained by the very institutions shaped by the epidemic.

In 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, health care workers, patients, and community members gathered at NYC Health + Hospitals/Woodhull in Bedford-Stuyvesant for a World AIDS Day vigil marking four decades since the first cases of AIDS were reported in the United States. https://ny1.com/nyc/all-boroughs/news/2021/12/01/nyc-world-aids-day-vigils

Share Your Story

Your voice matters. If you have memories, photographs, or reflections connected to the AIDS crisis in New York City, we invite you to share them. Together we can preserve these histories and ensure they are never forgotten.