Stonewall National Monument and AIDS Memorialization

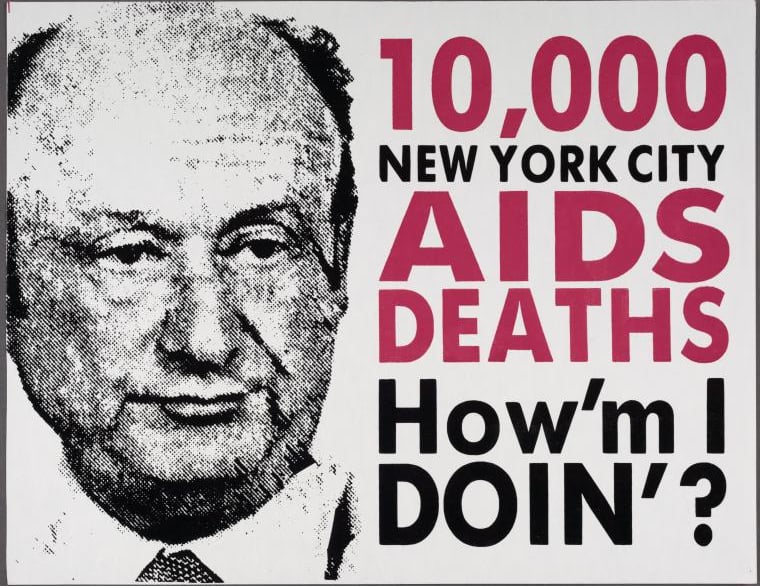

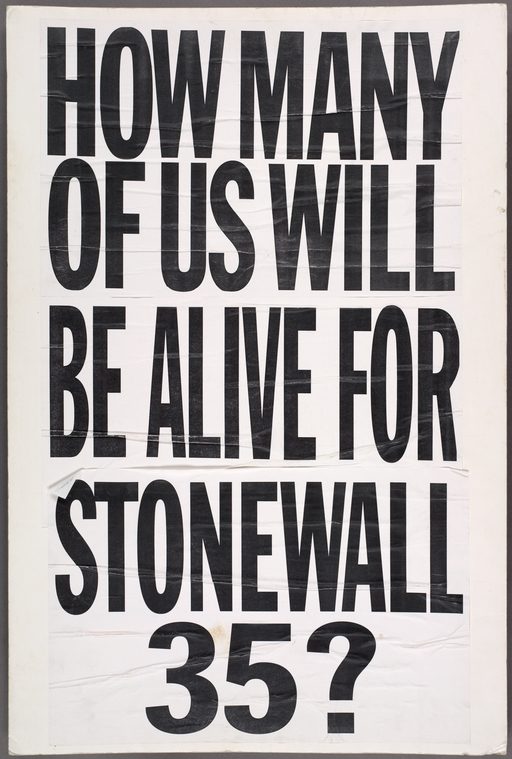

ACT UP Poster, 1994

Produced for the 25th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, this ACT UP poster asked, “How many of us will be alive for Stonewall 35?” The question underscored the devastating toll of AIDS at a moment when thousands were still dying each year, demanding that Stonewall’s legacy of defiance be linked to the unfinished fight for survival. By invoking Stonewall’s milestone through the lens of AIDS, ACT UP insisted that queer liberation and the epidemic could not be separated—and that remembrance itself was a form of resistance. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Why include Stonewall in a history of AIDS memorialization, when the epidemic would not begin until more than a decade later? The answer lies in how Stonewall reshaped queer politics, space, and memory. The 1969 uprising at the Stonewall Inn marked a pivotal turning point in LGBTQ+ history, shifting queer life from invisibility to a militant presence. The strategies and solidarities forged in the aftermath of Stonewall —direct action, public mourning, Pride parades, and the proliferation of queer spaces —would become the foundations upon which communities confronted AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s.¹

In the 1970s, organizations such as the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) pioneered tactics that AIDS activists later adopted. GLF’s coalition politics and GAA’s theatrical “zaps” against politicians introduced new forms of direct action, while candlelight vigils and marches transformed private grief into public visibility.² Pride parades, first held to commemorate Stonewall, became annual rituals of remembrance and resistance, establishing a framework that AIDS memorialization would expand.³

At the same time, the post-Stonewall decade witnessed an unprecedented flourishing of queer life. New bars, bookstores, theaters, and businesses made gay culture increasingly visible.⁴ The piers, bathhouses, and nightclubs of Greenwich Village and Chelsea became laboratories of sexual freedom and community connection. At the same time, advocacy groups such as the Gay Men’s Health Project and the Lesbian Herstory Archives solidified queer institutional presence. Out of these worlds, people forged “found families,” bonds of love, friendship, and solidarity that proved indispensable when AIDS struck.⁵ When many families of origin and state institutions abandoned those with AIDS, these networks became lifelines of caregiving and activism. The social transformations sparked by Stonewall thus directly shaped how queer communities survived and memorialized the epidemic.

This continuity was not abstract; it was lived. Many Stonewall-era activists themselves died of AIDS-related illnesses. Jim Owles, the first president of the GAA, succumbed in 1993.⁶ Morty Manford, another GAA leader who helped frame early activism around public mourning and advocacy, died in 1992.⁷ Marty Robinson, known for his theatrical “zaps” that forced LGBTQ+ issues into public view, also died of AIDS.⁸ Their deaths underscored how the very generation that had sparked liberation in the 1970s carried that spirit into the 1980s, only to be decimated by the epidemic.

In 1989, when Mayor Ed Koch symbolically renamed the street “Stonewall Place,” ACT UP protestors held placards shaped like tombstones, indicting his failed AIDS policies. The mayor fled the platform, unable to be heard above the din of protests. Getty Images/Newsday LLC.

A month after the Stonewall Uprising, activist Marty Robinson addresses a crowd of approximately 200 people before leading the first mass rally in support of gay rights in New York on July 27, 1969. Robinson died from complications of AIDS in March 1992.The New York City LGBT Center holds an archive of his papers.Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

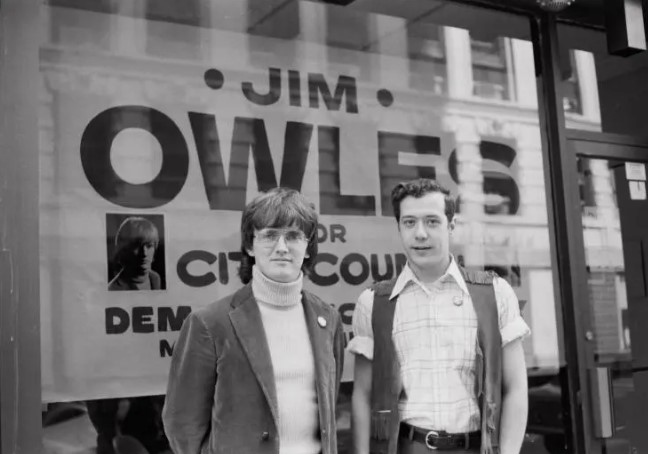

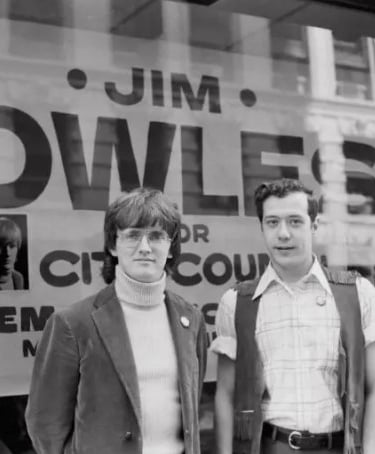

Jim Owles (left) and Morty Manford (right), 1973

Photographed here in 1973, Jim Owles and Morty Manford represent the generation of activists who carried Stonewall’s spirit into the political arena. Both were founding members of the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), formed in the wake of the 1969 uprising to channel street rebellion into direct action and institutional change. Owles, the first openly gay candidate for public office in New York City, had already transformed grief into protest during the 1970 Snake Pit raid, leading a solemn march to St. Vincent’s Hospital, where dozens of gay men were hospitalized. Manford, whose activism was shaped by that same vigil, went on to co-found PFLAG with his mother Jeanne Manford, create one of the first queer student spaces at Columbia University, and later join the National New Orleans Memorial Fund to honor the victims of the 1973 Upstairs Lounge fire—the deadliest attack on a gay bar in U.S. history.

Their activism linked Stonewall to a growing culture of public mourning and visibility, establishing rituals of protest and remembrance that would become central during the AIDS epidemic a decade later. Both men would themselves die of AIDS—Manford in 1992, Owles in 1993—placing their own lives within the very cycle of activism, loss, and memorialization they helped to forge. Together, they embody the bridge between Stonewall’s liberation and AIDS activism’s demand that queer lives and deaths be seen, named, and remembered. Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen, courtesy of the Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Christopher Park, at the heart of the Stonewall National Monument, became a memorial landscape. During the AIDS crisis, it hosted vigils, name-readings, and marches where grief and protest converged. Pride parades incorporated AIDS remembrance through moments of silence, quilt panels carried through the streets, and banners naming the dead.⁹ Installed in 1992, George Segal's Gay Liberation monument was conceived to honor Stonewall but quickly accrued additional meaning as an AIDS memorial. Its white-bronze figures, positioned at eye level and often adorned with flowers, ribbons, and protest signs, embody a dual purpose: celebrating liberation while absorbing the weight of absence.¹⁰

Yet official memorialization at Stonewall has not always reflected the breadth of queer history. Segal's figures depict white, cisgender men and women, a choice long criticized for excluding those most central to the uprising, including Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson. Both trans women of color were visible defenders of the community at Stonewall, and both later confronted the compounded burdens of poverty, racism, and AIDS. Johnson became a caretaker for people with AIDS, while Rivera denounced the marginalization of trans voices in both Stonewall commemorations and AIDS advocacy.¹¹ Their absence from official memorials mirrors broader patterns of exclusion in AIDS remembrance, where Black, Brown, transgender, and poor communities bore disproportionate losses yet were often left out of the narrative.

Julie Burna, head ranger of the Stonewall National Monument, emphasizes that Christopher Park is not a static historic site but a "living memorial" continually reshaped by community use. Visitors hang flags, leave flowers, and stage protests, transforming the park into a stage where memories are enacted.¹² She also acknowledges the challenges: tensions over representation, the invisibility of trans and people of color in Segal's statue, and the friction between grassroots memorial practices and official interpretation. These conflicts reveal how Stonewall remains contested ground at the intersection of memory, activism, and erasure.

Notes

David Carter, Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2004).

Martin Duberman, Stonewall (New York: Dutton, 1993), 232–65.

David Carter, Stonewall, 267–72.

Charles Kaiser, The Gay Metropolis: The Landmark History of Gay Life in America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997), 291–320.

George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994), epilogue; Audre Lorde, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (Freedom, CA: Crossing Press, 1982).

Kaiser, The Gay Metropolis, 314.

"Morty Manford, 41, Lawyer and Rights Advocate," New York Times, May 24, 1992.

David Carter, Stonewall, 319.

Marita Sturken, Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 196–202.

Genevieve Flavelle, "Not One Monument but 12: Re-memorializing the Stonewall Riots," Canadian Art, June 15, 2019.

Sylvia Rivera, "Queens in Exile, the Forgotten Ones," in GenderQueer: Voices from Beyond the Sexual Binary, ed. Joan Nestle, Clare Howell, and Riki Wilchins (Los Angeles: Alyson Books, 2002), 67–77.

Julie Burna, interview by author, October 31, 2024.

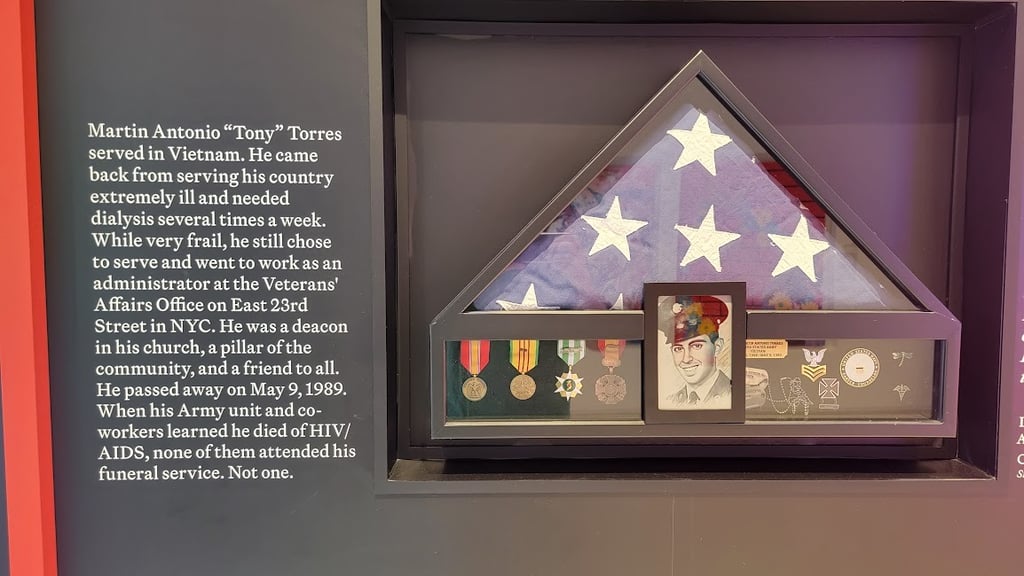

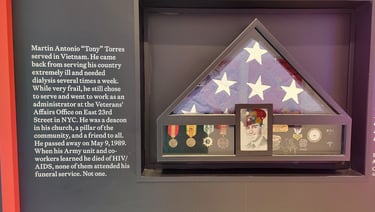

Tribute to Martin Antonio “Tony” Torres. The Stonewall National Monument’s Visitors Center, NYC. Oct. 31st, 2024. Photo by Joseph Golden.

Martin Antonio 'Tony' Torres served in Vietnam. He came back from serving his country extremely ill and needed dialysis several times a week. While very frail, he still chose to serve. Went to work as an administrator at the Veterans Affairs office on E 23rd St. in New York City. He was a Deacon in his church, a pillar of the community, and a friend to all. He passed away on May 9th, 1989. When his army unit and coworkers learned he died of HIV AIDS, none of them attended his funeral service. Not one.

The Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center

When the Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center opened on June 28, 2024, it marked a significant milestone in how the United States publicly tells the story of LGBTQ+ history. At the entrance, visitors are greeted by a deeply personal memorial curated by Diana Rodriguez in honor of her uncle, Martin Antonio “Tony” Torres, a Vietnam veteran who died of AIDS in 1989. His military medals and folded American flag are displayed beside the devastating truth. When his fellow service members and colleagues at the Veterans Affairs office learned he had died of AIDS, none of them attended his funeral. Not one.¹

This exhibit reframes the meaning of Stonewall by linking the 1969 uprising against invisibility to the epidemic defined by silence and stigma. Just as queer and trans people demanded to be seen in Greenwich Village, people with AIDS were forced to confront abandonment in the 1980s. Torres’s story insists that AIDS cannot be separated from the broader liberation struggle. Without his niece’s advocacy, his service and his suffering might have gone unacknowledged. Instead, his memory now greets every visitor, reminding them that LGBTQ+ history is not only about rebellion and pride, but also about caregiving, grief, and resilience.

The presence of Torres’s memorial demonstrates the power of personal stories to bridge gaps in public commemoration. Just as the nearby New York City AIDS Memorial anchors the epidemic in the geography of the West Village, the Visitor Center grounds AIDS memory in Stonewall’s legacy; together, they affirm that queer history is not static—it is alive, fragile, and always in need of protection against erasure.

Yet despite these strengths, the Visitor Center also reveals the challenges of official commemoration. Shaped by national narratives and corporate sponsorships, its overall tone risks softening the radical urgency of both the Stonewall and AIDS activism movements. As Holland Cotter observed in The New York Times, “What’s most disappointing… is the center’s informational softness, the suggestion it gives that the Stonewall rebellion and what it stood for is old history, and that now all’s OK.”² In an era of renewed attacks on LGBTQ+ rights and the continued marginalization of transgender people, this “softness” risks conveying a false sense of closure. The Visitor Center, like all memorials, reminds us that remembrance is never finished.

Notes

Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center, site visit and exhibit notes, October 31, 2024.

Holland Cotter, “Why Can’t New York Make a Proper Monument to Gay History?” The New York Times, June 28, 2024.

The Gay Liberation Statue. March 1st, 2025. Photo by Joseph Golden

In March 2025, anonymous activists dressed the figures of the Gay Liberation Monument in National Park Service ranger uniforms, draped benches with Pride and transgender flags and symbols. They placed a U.S. flag as a symbol of distress. A statement left at the site declared:

We once wore these clothes as National Park Service Rangers, who have been fired and are furious about the erasure of transgender and queer people from public record by this federal administration. LGBTQ+ people are, will be, and always have been inseparable from the story of America. Today at Stonewall, we resist these domestic attacks by flying the U.S. flag as a symbol of distress over the Gay Liberation Monument. Power to the people!

Stonewall, Erasure, and the Politics of Memory

Recent directives have placed new limits on how the National Park Service may represent queer and transgender history. In 2024, staff were instructed that Pride content could no longer appear on official websites, and rainbow or transgender flags could not be flown on federal property.¹ These changes effectively erase transgender visibility from the nation’s most symbolic LGBTQ+ historic site, narrowing Stonewall’s meaning to something safer and less controversial.

This erasure carries particular weight when viewed through the lens of AIDS memorialization. Transgender women of color, including Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, were central to the 1969 uprising and later became caregivers, advocates, and casualties during the AIDS epidemic.² To remove trans presence from Stonewall today repeats the exclusions of the 1980s and 1990s, when the disproportionate losses borne by trans and queer people of color were often omitted from public remembrance.

AIDS memorialization demonstrates that memory is fragile and politically contested. Who is recognized and who is omitted determines whether communities are honored or forgotten. Ensuring that Stonewall tells the full and complex story—including trans lives and the impact of AIDS—is not just about historical accuracy. It affirms dignity, combats shame, and connects people today to a past that remains vital for survival.

Notes

Robin Bravender, “Interior Revokes Biden-Era Encouragement of LGBTQ Pride Participation,” E&E News by POLITICO, June 4, 2024, https://www.eenews.net/articles/interior-revokes-biden-era-encouragement-of-lgbtq-pride-participation.

Sylvia Rivera, “Queens in Exile, the Forgotten Ones,” in GenderQueer: Voices from Beyond the Sexual Binary, ed. Joan Nestle, Clare Howell, and Riki Wilchins (Los Angeles: Alyson Books, 2002), 67–77.

Share Your Story

Your voice matters. If you have memories, photographs, or reflections connected to the AIDS crisis in New York City, we invite you to share them. Together we can preserve these histories and ensure they are never forgotten.