Hart Island: A Burial Ground at the Edge of Memory

Babies and Fetuses Buried on Hart Island in New York City. 1990. Claire Yaffa. https://gmpphoto.blogspot.com/2020/08/hart-island-new-york-potters-field.html

Hart Island is a small, windswept island in Long Island Sound, just off the eastern coast of the Bronx near City Island. Since 1869, it has served as New York City’s potter’s field—a municipal cemetery for people who were unclaimed or whose families could not afford private burials. Over the course of more than 150 years, more than one million New Yorkers have been interred there, most in long trenches, without individual headstones, ceremonies, or any visible markers to commemorate a life lived.¹ Because Hart Island was operated for decades under the jurisdiction of the New York City Department of Correction, and staffed by inmates from Rikers Island, it remained both geographically and civically marginal: an essential but obscured part of the city’s public-health infrastructure.² Visitors were not permitted unless they had secured special clearance. Burials were conducted out of view, under the logic of bureaucratic efficiency rather than emotional care.

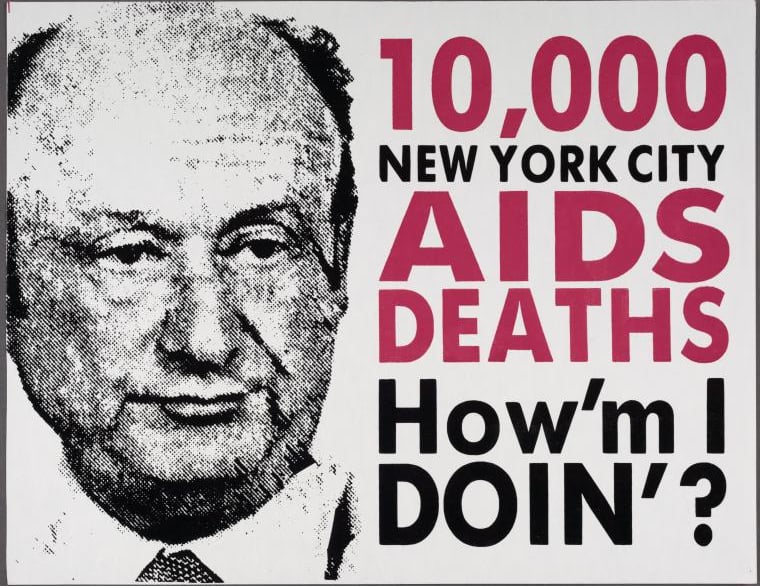

For those studying the politics of AIDS memorialization, Hart Island reveals a stark counterpoint to the more visible and participatory commemorative efforts that took root in New York City during the AIDS crisis. Unlike the New York City AIDS Memorial at St. Vincent’s Triangle or the quilt panels sewn in community centers and displayed in public parks, Hart Island rendered grief invisible. Many who died of AIDS-related illnesses, disproportionately people of color, immigrants, sex workers, and the poor, were buried on Hart Island, not by choice, but by structural necessity.³ Their names were recorded in municipal ledgers, but absent from the commemorative landscape that was taking shape elsewhere through marches, vigils, panels, and monuments. Hart Island became a burial ground of last resort, where stigma, poverty, and public neglect determined the terms of death and the conditions of remembrance.

This difference is not merely spatial; it is conceptual in nature. Hart Island reveals how remembrance itself is stratified by class, race, and access. In contrast to the New York City AIDS Memorial’s inscribed Walt Whitman quotation, designed to invite reflection, Hart Island remained a place where grieving was bureaucratized and held at a distance. As artist and advocate, Melinda Hunt observed, it was “designed to make people disappear, in life and in death.”⁴

Notes

Nina Bernstein, “Unearthing the Secrets of New York’s Mass Graves,” New York Times, May 15, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/05/15/nyregion/new-york-mass-graves-hart-island.html.

Leyla Vural, “Potter’s Field as Heterotopia: Death and Mourning at New York City’s Edge,” Oral History 47, no. 2 (Autumn 2019): 106–16, https://www.jstor.org/stable/45214476.

Bernstein, “Unearthing the Secrets”; Claire Yaffa, “Children with AIDS: Spirit and Memory,” New-York Historical Society, June 7–September 1, 2013, https://www.nyhistory.org/exhibitions/children-aids-spirit-and-memory-photographs-claire-yaffa.

Melinda Hunt, interview by Joseph Golden, October 12, 2024; Derek Kravitz and Jacob Geanous, “Hart Island Burials Taken Over by Tree Landscapers, Uprooting Families’ Hopes for Transformation,” The City, November 19, 2021, https://www.thecity.nyc/2021/11/19/hart-island-covid-memorial-new-york-city-potters-field; Sally Raudon, “Hart Island and the Paradox of Redemption,” Gotham Center for New York City History, June 3, 2021, https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/hart-island-and-the-paradox-of-redemption.

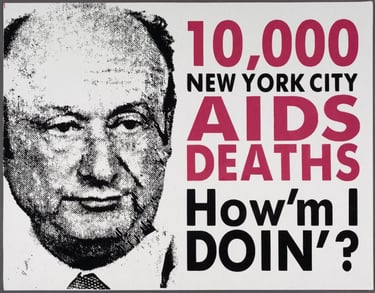

A Trench at the Potter’s Field on Hart Island, circa 1890

Photograph by Jacob Riis

Hart Island sits just off City Island in the Bronx, a low strip of land where New York City has buried its unclaimed and indigent dead since the late 1860s. During the final year of the Civil War, it served as a Union recruit depot and, briefly, as a camp for Confederate prisoners. Soon after, the City bought the island and, in 1869, opened the municipal “City Cemetery” to handle common burials; the first recorded interment, Louisa Van Slyke, took place that spring.¹ Making Hart Island the new site for Potter's Field burials consolidated an older practice: earlier municipal cemeteries, most famously beneath today’s Washington Square Park and at the future site of the New York Public Library’s Main Branch, had been filled or repurposed as the city grew.²

From the outset, Hart Island encoded distinctions of civic worth in death. Indigent veterans were set apart in a Soldiers’ Plot and, decades later, many of those remains were ceremonially reinterred to recognized military cemeteries, leaving an 1877 granite obelisk to mark the old ground. The city’s poor, by contrast, were laid in long, numbered trenches, their identities preserved chiefly in ledgers rather than on headstones. The different trajectories, named removals to honored ground for soldiers, continued anonymity for the indigent, track how law, benefits, and custom privileged some claims to remembrance over others.³

As the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth, the island drew the kinds of institutions New York preferred to keep at its edge: quarantine wards during disease scares, a workhouse and a boys’ reformatory, and an almshouse that also served as a hospital. Later came a Navy disciplinary post, a Cold War Nike missile site, and, from 1966 to 1976, Phoenix House’s rehabilitation program. Cemetery operations remained under correctional administration for most of this history, shaping every visit—permits, escorts, fences—and reinforcing the island’s peripheral place in civic memory. By the late 1950s, more than half a million New Yorkers had already been interred there.⁴

A revealing interlude came in the 1920s, when Harlem developer Solomon Riley began building an amusement resort at the island’s southern tip expressly for Black New Yorkers excluded from segregated suburban parks. Newspapers later remembered the plan as a proposed “Negro Coney Island.” Crews erected a dance hall, boardinghouses, a boardwalk, and a bathing pavilion before the City condemned the parcel, razed the buildings, and eventually repurposed the site for sewage infrastructure. This outcome underscored how race, class, and urban governance policed leisure and kept Hart Island’s identity as a place apart.⁵

During the AIDS crisis, the island’s role in managing marginalized death became newly visible. In 1985, amid fear and uncertainty about transmission, the city buried sixteen people who had died of AIDS in deep, individual graves at the remote southern tip; that year, an unnamed infant, long recorded as a “special case,” was interred in the island’s only single grave marked by a small concrete tablet. In the years that followed, thousands of New Yorkers who died of AIDS-related illness were buried on Hart Island, though the precise number is unknown. Early procedures gave way to standard trench interments as medical understanding improved, but the broader pattern held: those most exposed to poverty, stigma, and racism were the ones most likely to be buried out of view.⁶

Taken together, these layers —soldiers and paupers, quarantine and workhouse, an unbuilt amusement park, the epidemic dead —make Hart Island more than a cemetery. It is a ledger of how the city has managed grief at its margins and how recognition in death has been uneven by design. That is why the island remains central to conversations about access, equity, and remembrance in New York’s AIDS memory landscape: it shows, with stark clarity, who has been named, who has been counted, and who has been kept out of sight.

Notes

“Purchase of Hart’s Island,” New York Times, February 27, 1869; Alyssa Loorya and Eileen Kao, “Phase IA—Documentary Study and Archaeological Assessment for the Hart Island, Bronx (Bronx County), New York—Shoreline Stabilization Project” (New York: New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, 2017), PDF.

“In the Potter’s Field; Burying the City’s Pauper Dead,” New York Times, March 3, 1878; Loorya and Kao, Phase IA—Documentary Study and Archaeological Assessment.

The Hart Island Project, “Hart Island Soldiers’ Cemetery,” accessed September 26, 2025; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration, “Cypress Hills National Cemetery,” accessed September 26, 2025.

“Grand Jury Says Hart’s Island Tuberculosis Ward Is Unsuitable,” New York Times, November 10, 1917, 13; “Likes Life in Workhouse: Inmate Writes of ‘Good Eats, No Work, and Bum Arguments,’” New York Times, October 3, 1915; Nan Robertson, “About New York; City’s Unclaimed Dead Lie on Lonely Tip of Hart Island Off the Bronx,” New York Times, September 22, 1958.

“FYI,” New York Times, March 1, 1998 (item on the proposed “Negro Coney Island”).

Melinda Hunt and Joel Sternfeld, Hart Island (Zurich: Scalo, 1998), 83; Corey Kilgannon, “Dead of AIDS and Forgotten in Potter’s Field,” New York Times, July 3, 2018; Lizzy Ratner, “The Search for Special Case–Baby 1,” The Nation, March 12, 2024.sland Burials Taken Over by Tree Landscapers, Uprooting Families’ Hopes for Transformation,” The City, November 19, 2021, https://www.thecity.nyc/2021/11/19/hart-island-covid-memorial-new-york-city-potters-field; Sally Raudon, “Hart Island and the Paradox of Redemption,” Gotham Center for New York City History, June 3, 2021, https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/hart-island-and-the-paradox-of-redemption.

“Special Child–Baby 1” and the year of their burial, 1985. The grave belongs to the first child to have died of AIDS in New York City. Joel Sternfield. https://www.joelsternfeld.net/artworks/2018/3/25/happy-anniversary-sweetie-face-k9yy5

Burial as Erasure: Hart Island and the Carceral Logic of Mourning

Hart Island looks peaceful from a distance, but its quiet hides a harsher truth. More than a million people are buried there, without ceremony, gravestones, or individual records. Many were among the most marginalized in New York City: gay men, intravenous drug users, sex workers, unhoused people, and babies born with HIV/AIDS. As artist and activist Melinda Hunt has written, the city’s burial system was “designed to make people disappear, in life and in death.”¹

For decades, burials were carried out not by funeral workers but by incarcerated men brought from Rikers Island. They dug trenches wide enough for 150 pine coffins—three across, stacked three deep. Infants and children, many stillborn or perinatally infected with HIV, were buried separately, often 40 to 50 at a time each week.² With no funerals, no headstones, and no rituals, Hart Island became what one observer called “a resting place for those who lived without dignity and died without notice.”³ This reflects what the scholar Kenneth Doka calls disenfranchised grief: mourning that society refuses to recognize or support.⁴

During the worst years of the AIDS epidemic, many who died of AIDS-related illnesses ended up on Hart Island. Families sometimes turned away in fear; funeral homes refused their bodies. Burials on Hart Island were not a matter of choice, but of abandonment. As one activist later put it, “They weren’t just dying alone. They were buried without names, without stories, without acknowledgment of who they were.”⁵ The demographics of Hart Island, disproportionately Black and Latino New Yorkers, gay men, people who used injection drugs, and the unhoused, tell a different story of AIDS than the one often centered on white, middle-class gay men. Hart Island reveals who was most likely to be erased from public memory.

The French theorist Michel Foucault once described cemeteries as heterotopias, spaces that exist outside ordinary life but reflect society’s values and exclusions.⁶ Hart Island embodies this idea. Geographically removed from the city, long closed to visitors, and largely hidden from public view, it mirrors the social isolation of those buried there. Hunt has said, “Hart Island is a place where the city’s unwanted go to disappear, but it’s also a mirror reflecting who we are as a society.”⁷ What we bury here—physically and symbolically—shows whose lives are treated as worthy of grief, and whose are not.

The process of burial itself also reveals the state’s carceral logic. Incarcerated men from Rikers Island performed the final rites for New Yorkers abandoned by their families and by public institutions. One former worker recalled: “When you’re there and you’re burying these bodies... you start thinking about your own life. It really makes you reflect on your own mortality.”⁸ Another described how he tried to honor the dead: “I’d bury them, and in my mind, I’d make sure they weren’t left alone. It might have been a pine box with just a name on it, but they were human, they were loved, and they mattered.”⁹

This paradox—incarcerated people burying others who had been erased by the state—makes Hart Island a place where punishment, grief, and historical erasure converge. It is not only a cemetery but a geography of social judgment, a heterotopia of carceral mourning.

Notes

Melinda Hunt and Joel Sternfeld, Hart Island (Zurich: Scalo, 1998), 12.

Hunt and Sternfeld, Hart Island, 47–49.

Melinda Hunt, quoted in Lizzy Ratner, “The Search for Special Case–Baby 1,” The Nation, March 12, 2024.

Kenneth J. Doka, Disenfranchised Grief: Recognizing Hidden Sorrow (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1989).

Corey Kilgannon, “Dead of AIDS and Forgotten in Potter’s Field,” New York Times, July 3, 2018.

Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias,” Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, 1984.

Hunt and Sternfeld, Hart Island, 93.

Quoted in Nina Bernstein, “Unearthing the Secrets of New York’s Mass Graves,” New York Times, May 15, 2016.

Testimony from The Hart Island Project, archived oral history.

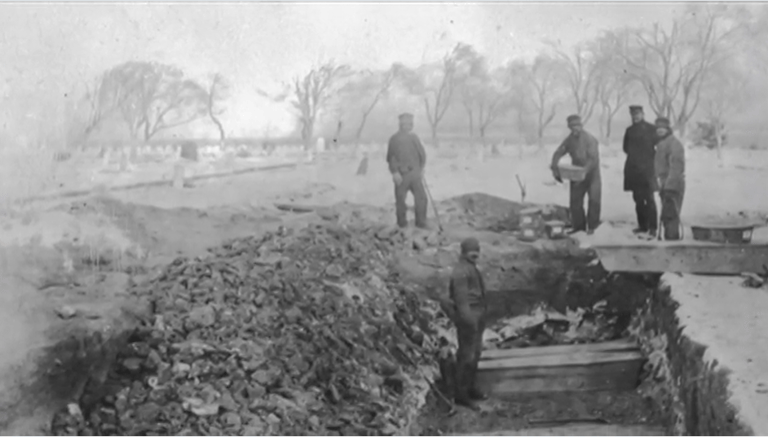

Incarcerated men from the Rikers Island jail buried adults in a mass grave on Hart Island in 1992. Joel Sternfeld https://www.joelsternfeld.net/artworks/2018/3/25/happy-anniversary-sweetie-face-k9yy5

Artists, Witnesses, and Making Hart Island Public

From the early 1990s onward, artists and journalists have been instrumental in transforming Hart Island from an administrative ledger into a site of public memory. Artist Melinda Hunt, working with photographer Joel Sternfeld, began documenting the cemetery and its operations in 1991. Their book, Hart Island (1998), paired photographs with research into burial practices and governance, establishing the evidentiary foundation for years of advocacy.¹ Hunt then founded The Hart Island Project, which assembled burial data, mapped plots, and pressed for humane family access—shifting the island’s narrative from secrecy to remembrance and building the infrastructure for public engagement.²

Photographer Claire Yaffa added a vital visual ethics to that record. Beginning in 1990, she documented children living with HIV/AIDS at the Incarnation Children’s Center; her related images and later exhibition at the New-York Historical Society made visible the intimate costs of the epidemic and, for some families, pointed back to Hart Island as a burial site.³ Her photographs operate as both elegy and evidence: they restore faces to statistics and insist that dignity in death is a public concern.³

Journalists amplified this work and widened access. Investigative reporting synthesized scattered municipal files, mapped burial trenches, and showed families how to navigate a system that had long kept them at the margins. Nina Bernstein’s 2016 New York Times investigation visualized scale and procedure for a broad audience, while Corey Kilgannon’s 2018 reporting on AIDS burials (including the infant long recorded as “Special Case—Baby 1”) demonstrated how public records and testimony can surface lives otherwise lost to stigma and paperwork.⁴ ⁵

Policy followed pressure. Through litigation, hearings, and sustained coverage, the city expanded visitation and access to records. It began transferring Hart Island’s management away from the Department of Correction toward parks and social-service stewardship, reframing the cemetery as a place of remembrance rather than a penal backwater.⁶ Implementation has been uneven, as local reporting on contracting and maintenance makes clear; however, the trajectory is toward greater transparency, access, and care.⁷

Hunt’s most influential tool is the Traveling Cloud Museum: a participatory, searchable interface that links burial records to individual pages where relatives and community members can add stories, images, or epitaphs. When a contribution is made, the page’s “clock” (measuring time since burial) stops, an intentional design that turns administrative entries into acts of remembrance.⁸ Scholars argue that this participatory model not only interrupts anonymity but also decenters whiteness in AIDS memory by foregrounding indigent, immigrant, Black, and Brown experiences that standard memorial forms have often neglected.⁹

Why this matters for memorialization, past, present, and future: twentieth-century AIDS memory work—exemplified by quilts, vigils, and monuments—built powerful spaces for collective grief but rarely captured those buried without ceremony or kin. The Cloud Museum extends that ethic into digital space, inviting the public to help repair the archive and to treat remembrance as ongoing civic labor. As cultural historian Marita Sturken notes, adequate AIDS memorials must hold both personal loss and political silence; a hybrid of records, images, testimonies, and on-island access does precisely that.¹⁰ Preservation research now underwrites this future work—stabilizing shorelines, standardizing maps, and clarifying what can be done without disturbing graves—so that memory has durable ground as well as a living, editable record.¹¹

Notes

Melinda Hunt and Joel Sternfeld, Hart Island (Zurich: Scalo, 1998).

The Hart Island Project, “About,” accessed September 27, 2025, https://www.hartisland.net/about.

New-York Historical Society, Children with AIDS: Spirit and Memory—Photographs by Claire Yaffa, exhibition materials, June 7–September 1, 2013; New-York Historical Society, “Claire Yaffa Children with AIDS Photographs, 1987–2010 (PR 290),” finding aid, https://findingaids.library.nyu.edu/nyhs/pr290_claire_yaffa_aids/.

Nina Bernstein, “Unearthing the Secrets of New York’s Mass Graves,” New York Times, May 15, 2016.

Corey Kilgannon, “Dead of AIDS and Forgotten in Potter’s Field,” New York Times, July 3, 2018.

City of New York, “Hart Island,” accessed September 27, 2025, https://www.nyc.gov/site/hartisland/hart-island/hart-island.page.

Derek Kravitz and Jacob Geanous, “Hart Island Burials Taken Over by Tree Landscapers, Uprooting Families’ Hopes for Transformation,” The City, November 19, 2021.

The Hart Island Project, “Traveling Cloud Museum,” accessed September 27, 2025, https://www.hartisland.net/.

Daniel C. Brouwer and Charles E. Morris III, “Decentering Whiteness in AIDS Memory: Indigent Rhetorical Criticism and the Dead of Hart Island,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 107, no. 2 (2021): 160–84, https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630.2021.1905868.

Marita Sturken, Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

Alyssa Loorya and Eileen Kao, Phase IA—Documentary Study and Archaeological Assessment for the Hart Island, Bronx (Bronx County), New York—Shoreline Stabilization Project (New York: New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, 2017), PDF.

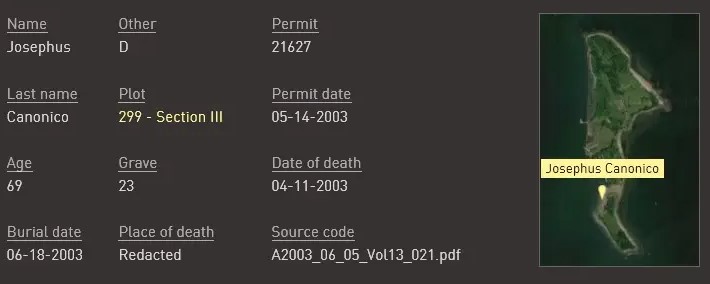

Grave Location (Entry View – Joseph Canonico)

This Hart Island Project entry connects Joseph Canonico’s burial record to a GPS pin on the island’s grid. The section–row–coffin reference appears alongside an interactive map, so families can visualize the trench location and understand how the cemetery is organized. By pairing municipal data with mapping, a line in the ledger becomes a place you can actually find. https://www.hartisland.net/

Personal Story (Community Memory Panel)

Next to the map, relatives and friends can add memories, photos, or an epitaph. For many, this is the first public space to speak about someone missing from their lives—lost to poverty, illness, stigma, or distance. Contributing a story halts the entry’s time-since-burial clock and restores presence and dignity to a name that once sat, silent, in a record. https://www.hartisland.net/

Hart Island is now more accessible than at any point in its long history, but access remains carefully structured. To visit, you must register in advance: public tours run only on select days, led by Urban Park Rangers, with demand often exceeding available spaces and entry determined by lottery.¹ Gravesite visits, where mourners can stand near the trench of a named person, are restricted to family, chosen family, or close friends, and also require advance booking.² A 2025 city plan envisions gradual improvements—a remembrance walk, shoreline protections, and a welcome area—but these will unfold over decades.³ In other words, the island is open, but only on the city’s terms. You cannot simply arrive as you might at a neighborhood park or cemetery. This tension between openness and control highlights Hart Island’s unique position in New York’s memorial landscape: a site of civic mourning where access itself becomes integral to the politics of memory.

Digital memorials attempt to widen that aperture. The Traveling Cloud Museum, for example, lets anyone search burial records and contribute stories or images that transform an entry from anonymity to remembrance.⁴ Its “clocks” mark the passage of time since burial without public acknowledgment, and when someone adds a memory, the clock stops—a small but powerful ritual. Scholars note that such participatory designs help surface lives often excluded from traditional AIDS remembrance, including indigent, immigrant, incarcerated, Black, and Brown New Yorkers.⁵ Yet online archives are not permanent. They require ongoing funding, technical maintenance, and curatorial oversight; without these, they risk fading into digital obsolescence.⁶

Placed alongside the Quilt, Pride marches, and the NYC AIDS Memorial in stone and steel, Hart Island complicates what it means to remember. The Quilt, stitched from fabric and grief, was built to travel; its power lies in scale and intimacy, in seeing a sea of names unfold in a gymnasium or on the Mall. Parades and vigils transformed public streets into sacred ground, making mourning visible through movement and sound. Stone and steel monuments, like the triangular canopy in Greenwich Village, anchor memory in permanence, offering a fixed place to return. Hart Island does none of these things easily. It is remote, bureaucratically mediated, and tied to a history of carceral practices. Yet precisely because of those conditions, it forces a different reckoning. Its trenches remind us that AIDS remembrance in New York has always been uneven: some deaths sanctified in fabric and marble, others left in pine boxes at the city’s edge. To remember Hart Island is to hold these forms together; to recognize that public memory is strongest not when one medium dominates, but when quilts, parades, monuments, and burial grounds are seen as parts of the same patchwork.

Notes

NYC Parks, “Urban Park Rangers: Hart Island Tours,” accessed September 27, 2025, https://www.nycgovparks.org/events/hart-island.

City of New York, “Gravesite Visitation—Hart Island,” accessed September 27, 2025, https://www.nyc.gov/site/hartisland/hart-island/gravesite-visitation.page.

NYC Parks, “NYC Parks Unveils the Hart Island Concept Plan,” press release, July 14, 2025, https://www.nycgovparks.org/sub_newsroom/press_releases/press_releases.php?id=22246.

The Hart Island Project, “About / Traveling Cloud Museum,” accessed September 27, 2025, https://www.hartisland.net/about.

Daniel C. Brouwer and Charles E. Morris III, “Decentering Whiteness in AIDS Memory: Indigent Rhetorical Criticism and the Dead of Hart Island,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 107, no. 2 (2021): 160–84.

National Digital Stewardship Alliance, Levels of Digital Preservation: An Explanation and Uses, rev. 2 (2019), https://ndsa.org/activities/levels-of-digital-preservation/.

Share Your Story

Your voice matters. If you have memories, photographs, or reflections connected to the AIDS crisis in New York City, we invite you to share them. Together we can preserve these histories and ensure they are never forgotten.