Pride as a Living Memorial

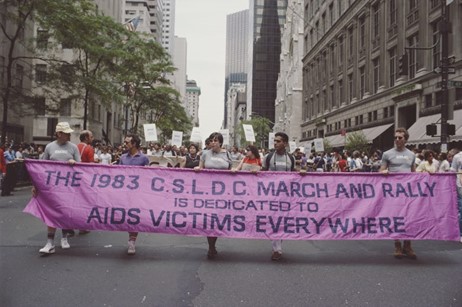

Christopher Street Liberation Day lead banner, New York City, June 1983.

“The 1983 C.S.L.D.C. [Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee] March and Rally Is Dedicated to AIDS Victims Everywhere.”

Initially known as the Christopher Street Liberation Day March, it was later renamed the "NYC Pride March" in 1984. In that year, Heritage of Pride (HOP) assumed responsibility for planning and production of the event from the disbanded Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee. Photograph, via Getty Images, in W Magazine, https://www.wmagazine.com/beauty/brunello-cucinelli-incanti-poetici.

Pride parades are often thought of as vibrant celebrations of LGBTQ+ life. Rainbow flags, music, and dancing fill the streets each June in a show of joy, identity, and unity. But during the 1980s, Pride became more than a party. It turned into a powerful form of public mourning. As the AIDS crisis spread and the government failed to act, the parade was transformed into a memorial on the move. People marched not only to be seen but also to remember. Banners carried the names of friends and loved ones who had died. Silence was held in the middle of the noise. Protest signs demanded attention to the crisis. In a time when few permanent monuments existed, Pride made grief visible.

To understand this transformation, it helps to return to the parade’s beginnings. The first Pride march was held in New York City in 1970, organized by the Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee to mark the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall Riots. That march was a radical act of defiance. It demanded visibility for LGBTQ+ people in a society that treated them as invisible. Its spirit was confrontational and unapologetic, rooted in the liberation politics of the early gay rights movement. Pride was first and foremost a march for freedom, resistance, and the right to occupy public space.

By the early 1980s, however, the tone of the parade began to shift. As the movement gained visibility, some organizers emphasized celebration over protest, seeking to broaden the appeal of Pride. Journalist Randy Shilts described this turn: “Parade organizers had decided that the event had grown too political in recent years, so the chest-pounding rhetoric that marked most rallies was given a backseat to the festive feeling of a state fair.”¹ What had once been a fierce assertion of rights was becoming a more carnival-like display of community.

That change was interrupted by the devastation of AIDS. As the crisis deepened, Pride returned to its roots in protest but also took on new layers of grief and remembrance. Marchers carried placards with the names of the dead, observed moments of silence, and confronted officials who had turned away. Activist groups like ACT UP infused the parade with militant energy, ensuring that the epidemic could not be ignored. Pride became not only a celebration of identity but a living memorial. It was a place where joy and mourning stood together, where grief fueled resistance, and where the community declared that queer lives mattered.

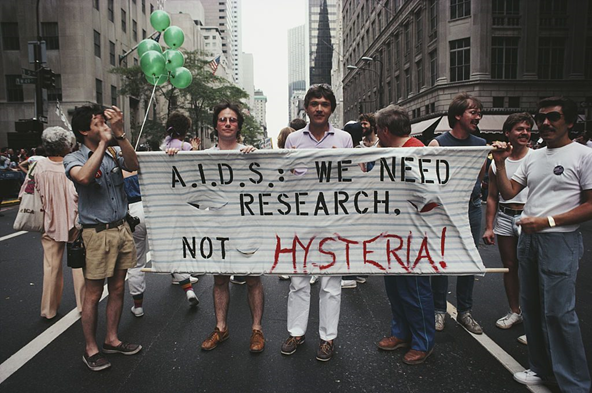

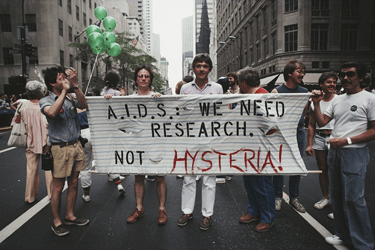

PWA (People With AIDS) Coalition, New York City, Lesbian and Gay Pride Parade 1983.

The Inclusion of AIDS Activism in Pride (1983 and Beyond)

In 1983, the profound effects of AIDS compelled Pride organizers to reassess the event’s significance. That year, AIDS diagnoses in New York City surged from 541 in 1982 to 1,098 in 1983, more than doubling in just twelve months.¹ While the 1983 parade was officially dedicated to individuals affected by the epidemic, its overall tone remained celebratory, reflecting the community’s resilience despite the mounting crisis. As Randy Shilts later wrote in And the Band Played On, this period reflected a relative naivety about the epidemic, symbolized by the “Before” phase, when many still clung to the freedom and joy that had defined the post-Stonewall era.² Yet even amid its festive spirit, the 1983 parade marked a turning point. The participation of Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) and the People With AIDS Coalition signaled the emergence of an organized response. For the first time, “We Remember” banners bearing the names of the dead appeared, weaving grief into the fabric of the parade and introducing public memorialization into a space once defined primarily by affirmation and celebration.³

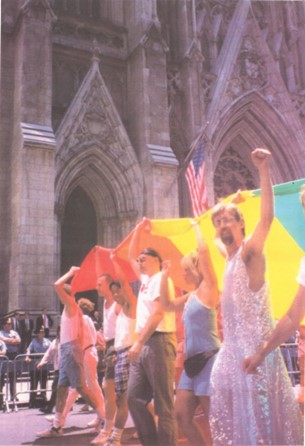

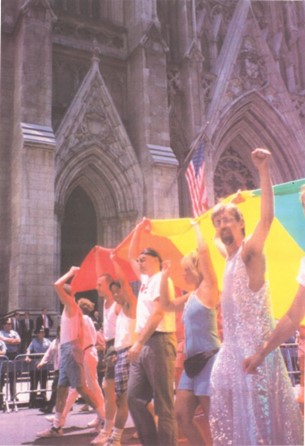

A powerful image from that year captures this shift: members of GMHC standing outside St. Patrick’s Cathedral, holding a handmade banner reading “Fighting for Our Lives.” The juxtaposition was striking: queer men protesting quietly beneath the stone façade of an institution that had remained largely silent about the epidemic.⁴ Like the Quilt, the banner was fabric-based, mobile, and deeply personal, but its message was urgent and defiant. By bringing grief to the cathedral steps, activists transformed sacred space into a site of confrontation. Visibility, in this sense, meant more than being seen; it meant demanding justice. Yet contemporary coverage suggests that AIDS was still treated as a secondary concern. ABC News reported that while the event was meant to be solemn, it was instead “much more upbeat, dedicated more to the theme of ‘we want dignity.’”⁵ Similarly, The New York Times noted that people living with AIDS marched behind a banner declaring “Fighting for Our Lives,” but described the parade overall as celebratory.⁶

Meanwhile, in San Francisco, the community’s response to AIDS reflected a markedly different tone. Widespread fears of casual transmission led to serious discussions about canceling the 1983 parade altogether. The concern was so pervasive that the city’s health commissioner issued an official statement reassuring attendees that the event posed no risk to their health.⁷ The contrast is telling. While New York’s parade foregrounded visibility, resilience, and joy, San Francisco’s response was defined by caution, public mourning, and heightened anxiety. These regional differences reflected deeper variations in culture, political sensibilities, and community structures, shaping how each city would later approach commemorative practices such as the AIDS Memorial Quilt.

By 1984, however, New York’s Pride parade began to shift more decisively from celebration to protest. The mounting toll of the epidemic, coupled with the Reagan administration’s silence, hostile media coverage, and the growing backlash of the religious right, made complacency impossible. In that year alone, AIDS diagnoses in New York nearly doubled, rising by ninety-nine percent, while AIDS-related deaths increased by 129 percent.⁸ Pride could no longer exist as a celebration alone; it had become a space to grieve, demand action, and resist institutional indifference.

The 1984 march underscored this transformation. Activists staged a sit-in at St. Patrick’s Cathedral to protest Archbishop John J. O’Connor’s refusal to comply with Executive Order 50, which prohibited city-funded organizations from discriminating based on sexual orientation.⁹ At the time, the Archdiocese controlled $76 million in city contracts for social services, yet resisted adherence to local anti-discrimination laws because compliance would condone homosexuality.¹⁰ The AIDS crisis intensified the stakes of this conflict, fueling stigma and reinforcing barriers to care, housing, and health services. Despite police presence and opposition from Catholic War Veterans, protesters asserted their visibility through both confrontation and memorial ritual. Members of Dignity, a Catholic LGBTQ+ group, laid a wreath at the cathedral steps. Simultaneously, marchers released balloons inscribed with “We Are Everywhere,” a public declaration of presence and resistance against religious condemnation and AIDS stigma.¹¹

By this point, the homophobic backlash, moral panic, and political exclusion of the AIDS era had galvanized LGBTQ+ protest. Activists returned to earlier tactics of the Gay Liberation movement—marches, sit-ins, and raised fists—while blending them with newer forms of festivity and affirmation. This hybrid style produced a distinctive visual language, characterized by handmade banners, cloth signs carried shoulder-high, choreographed street presence, and slogans that fused mourning with militancy. One sign from 1984 read, “We need research, not hysteria,” crystallizing in six words the movement’s shift from pleading for recognition to demanding survival.¹² In an era where moral panic outweighed public health, these messages insisted on science, care, and accountability. Photographs from the period often show protesters with fists raised and grief visible, capturing how mourning itself became an act of confrontation.

Footnotes

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, HIV Surveillance Annual Report, 2013, Table 2, https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/ah/surveillance2013-trends-tables.pdf.

Randy Shilts, And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987), 15.

Douglas C. McGill, “Homosexuals’ Parade Dedicated to AIDS Victims,” New York Times, June 27, 1983, Section B, 3, https://www.nytimes.com/1983/06/27/nyregion/homosexuals-parade-dedicated-to-aids-victims.html.

Figure 23: Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), 1983 NYC Pride Parade. Courtesy of Owen Franken.

Ed Miller, “1983 Pride Parade Coverage,” Eyewitness News ABC7NY, YouTube video, posted March 10, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JcVOxgWM7j0.

ABC News, Gay Pride Marches Highlight AIDS Awareness, archival news report, June 26, 1983, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IEaueKvFO6A.

Shilts, And the Band Played On, 19–20.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, HIV Surveillance Annual Report, 2013.

David Bird, “Thousands Hold March to Back Homosexuals,” New York Times, June 25, 1984, https://www.nytimes.com/1984/06/25/nyregion/thousands-hold-march-to-back-homosexuals.html.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“Timeline,” New York City AIDS Memorial, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.nycaidsmemorial.org/timeline.

PWA (People With AIDS) Coalition, New York City, Lesbian and Gay Pride Parade 1983.

1986: Pride, Grief, and Solidarity in the Face of Crisis

On June 29, 1986, New York City’s Pride march unfolded as a pageant of triumph and tragedy. That spring, the City Council had finally passed Intro 2, a long-awaited gay rights bill prohibiting discrimination in housing, employment, and public accommodations. The legislation represented a landmark victory for LGBTQ+ rights in New York. Organizers embraced a rainbow motif to mark the occasion, stringing enormous arches of rainbow-colored balloons above Fifth Avenue to symbolize hope and diversity. Yet beneath the brilliant colors, a harsher reality marched in plain view. Leading the 200,000-strong procession were participants in wheelchairs and on walkers, many visibly weakened by AIDS. The People With AIDS (PWA) Coalition carried banners demanding recognition, while caregivers and volunteers from GMHC and God’s Love We Deliver marched beside them. What had once been a celebration of defiant joy had become a procession of the dying and the grieving, forcing visibility on a city that often turned away.¹

In 1986, the AIDS crisis had escalated dramatically in New York, with 4,224 new diagnoses—nearly double the 2,869 recorded the year before.² Randy Shilts identified this year as the beginning of the “After” phase, when AIDS could no longer be dismissed as a marginal issue.³ By then, the epidemic had moved from rumor to constant reality, reshaping both media coverage and gay community life. Journalist David France later described the 1986 Pride Parade as a turning point: “The parade was no longer just about celebration—it was about making the epidemic visible to the city at large. It was a moment when the invisible deaths of thousands became visible.”⁴

The tone of Pride had shifted. Grief and protest now marched alongside joy and affirmation. Yet in this transformation, continuities endured. The act of claiming public space—marching, dancing, and demanding to be seen—echoed the liberationist traditions of the 1970s. Rather than replacing earlier forms of protest, the AIDS-era parade extended them, blending remembrance, defiance, and celebration into one evolving ritual.

Richard Ferrara, a longtime activist and early member of Heritage of Pride (HOP), helped shape this dual spirit of grief and resilience in 1986. He constructed banners and flags, coordinated the release of balloons following the Moment of Silence on the steps of the New York Public Library, and balanced the parade’s celebratory elements with recognition of devastating loss. Reflecting on the moment, Ferrara explained, “We needed the joy—it wasn’t about ignoring the pain but finding a way to keep going, to resist by celebrating who we were.”⁵ His philosophy ensured that Pride remained both a celebration of rights won and a statement of survival in the midst of crisis.

Despite the growing death toll, Pride in 1986 carried forward the flamboyance and exuberance of earlier parades. Public displays of affection, floats blasting music, and the presence of drag queens, drag kings, and members of the leather community reaffirmed the continuity of queer joy. These expressions, far from being diminished by AIDS, became bolder and more vital. At a time of profound loss, asserting visibility, identity, and sexual freedom in the streets was itself an act of defiance.

The religious dimension of the struggle was also on display. As in earlier years, demonstrators protested outside St. Patrick’s Cathedral, confronting the Catholic Church’s resistance to LGBTQ+ rights and its silence on AIDS. Antigay protesters often claimed the epidemic was divine punishment, but activists countered these narratives with symbolic acts of inclusion. Ferrara worked with churches along the parade route to toll bells during the annual Moment of Silence, reclaiming sacred sound in the service of solidarity rather than exclusion.⁶

This use of religious space echoed earlier traditions of candlelight vigils and protests outside churches in the 1970s and early 1980s. For Ferrara and others, religion was not simply an arena of rejection but also a contested and potentially transformative space. By the mid-1980s, as AIDS forced questions of mortality, grief, and moral authority into sharper focus, activists recognized that the fight for inclusion could not remain separate from the institutions that shaped public values. Pride in 1986 thus stood at the intersection of liberation and mourning, confrontation and celebration—a living memorial in motion.

Footnotes

Figure 24: People With AIDS (PWA). 1986 Lesbian and Gay Pride Parade. Barbara Alper/Getty Images.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, HIV Surveillance Annual Report, 2013, Table 2, https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/ah/surveillance2013-trends-tables.pdf.

Randy Shilts, And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987), 343.

David France, How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS (New York: Knopf Doubleday, 2016), 227–28, Kindle edition.

Richard Ferrara, phone interview by Joseph Golden, December 15, 2024.

Ibid.

Pride, 20th Anniversary of Stonewall, New York Public Library, June 25, 1989

The Gay Cable News Network captured the Moment of Silence on the steps of the New York Public Library during the 20th anniversary of Stonewall, as the Pride march paused. The crowd lifted pink ribbons inscribed with the names of loved ones lost to AIDS as a deep-purple banner reading WE REMEMBER was unfurled across the Library’s facade. White, pink, and purple balloons floated upward, transforming grief into collective visibility. The Library—long a site of ACT UP protests and today home to one of the country’s largest LGBTQ and AIDS archives—was transformed into a stage for mourning and resistance, echoing the defiant spirit of Stonewall. Gay Cable Network, Lesbian and Gay Pride Parade, 1989, June 25, 1989. 00:10:14.020. Fales Library and Special Collections, NYU. https://findingaids.library.nyu.edu/fales/mss_231/video/5qftts9b/.

ACT UP and the Transformation of Pride, 1987

By 1987, the AIDS crisis had become impossible to ignore. That March, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) was founded in New York City in response to the government’s inaction and the soaring cost of the only available treatment, AZT. Just three months later, ACT UP staged its first major demonstration on Wall Street. The group quickly distinguished itself through direct action, civil disobedience, and a media-savvy theatricality that drew upon earlier traditions of Gay Liberation protest.

That June, ACT UP made its first major appearance at the New York City Pride Parade. Their presence marked a turning point, bringing militant AIDS activism into one of the movement’s most visible stages. Marchers chanted “ACT UP! FIGHT BACK! FIGHT AIDS!” and carried stark banners that pierced the celebratory mood with urgent demands.¹ Protest was not a rejection of Pride’s celebratory spirit but a reimagining of it. ACT UP insisted that joy and grief, protest and performance, belonged together.

ACT UP’s Concentration Camp Float. New York, 1987. Avram Finkelstein https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/17506980211054355

Their visual strategies were deliberately confrontational. Members staged a die-in on Fifth Avenue, collapsing onto the pavement in a choreographed act of mourning and defiance.² One of their most striking contributions was a float designed to resemble a concentration camp, complete with members posing as guards and “prisoners,” one of whom wore a Ronald Reagan mask. Avram Finkelstein, who helped design the float, recalled the effect: “We were surprised at how imposing and frightening it felt.”³ The float directly accused the federal government of negligence, equating its silence with complicity in mass death.

ACT UP’s theatrical interventions at Pride extended beyond spectacle. They transformed the parade into a proving ground for tactics that would define the movement—die-ins, political funerals, and the repurposing of queer performance as political theater. Their slogan, SILENCE = DEATH, became inseparable from Pride itself, challenging not only the government’s refusal to act but also the danger of treating mourning as passive.

By bringing grief and rage directly into the Pride Parade, ACT UP made it clear that AIDS was not a private tragedy but a public emergency. Pride in 1987 became a space where mourning was protest, and protest was inseparable from joy. The arrival of ACT UP ensured that the AIDS crisis could no longer be ignored on the city’s most visible stage.

Footnotes

Tim Murphy, “A Timeline of HIV/AIDS Representation at New York City’s Pride March, From the Early 1980s to Modern Times,” The Body, July 1, 2024, https://www.thebody.com/article/timeline-hiv-representation-nyc-pride-march.

Ibid.

Avram Finkelstein, quoted in Journal of Visual Culture, “AIDS and Political Art: ACT UP’s Visual Strategies,” 2021, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1750698021105435

Mile-Long Pride Flag, 1994. NYC. Photo by Rick Hicks. Courtesy of the Gilbert Baker Foundation. https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/gilbert-baker-raise-the-rainbow-workshop/https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/gilbert-baker-raise-the-rainbow-workshop/

Stonewall 25 and the Waning of AIDS Visibility

By the mid-1990s, Pride in New York City was no longer dominated by the imagery of AIDS that had defined much of the 1980s. AIDS remained devastating; by 1994, it was the leading cause of death for American men aged 25 to 44, and in New York City alone, more than 54,000 people had died.¹ Yet the prominence of AIDS in the parade had diminished. Where earlier marches were marked by “We Remember” banners, die-ins, and long processions of AIDS organizations, the mid-1990s saw a shift toward a new emphasis on festivity, corporate floats, and mainstream political figures. The grief and militancy of the epidemic were still present, but increasingly confined to smaller contingents, overshadowed by the growing spectacle of Pride.

Stonewall 25, the 25th anniversary of the 1969 uprising, made this shift particularly visible. Heritage of Pride organizers rerouted the official march up First Avenue past the United Nations. Framed as a gesture toward international LGBTQ+ human rights, it bypassed symbolic sites of queer resistance such as St. Patrick’s Cathedral, where ACT UP had staged its 1989 “Stop the Church” protest.² For many activists, the new route symbolized Pride’s turn toward assimilation and political respectability, toward a vision of inclusion that left behind the confrontational energy of the AIDS years.

The centerpiece of the official commemoration was Gilbert Baker’s mile-long rainbow flag, carried by thousands of volunteers and celebrated worldwide as a record-setting spectacle.³ Visually stunning and widely covered by the press, the flag represented unity and inclusion. But for AIDS activists, its sheer scale and corporate sponsorship flattened the urgency of the crisis. ACT UP members criticized the flag as a symbol of depoliticization, a triumph of pageantry over protest. Baker himself recalled his frustration with corporate demands that he tone down his gender expression for media appearances, evidence of how consumer-friendly images increasingly shaped Pride.⁴

In response, ACT UP and grassroots organizers staged an Alternative March that retraced the original 1970 Christopher Street Liberation Day route up Fifth Avenue to Central Park. Carrying banners naming the dead and chanting militant slogans, they turned back to the radical ethos of Stonewall itself. One activist explained, “Giuliani said you can’t have Fifth Avenue for this thing. And we said, yes we can.”⁵ By marching past St. Patrick’s Cathedral and reclaiming the original route, ACT UP and their allies underscored that AIDS could not be erased from LGBTQ+ memory, even as official Pride sought to present a more polished, internationally marketable face.

Stonewall 25 thus marked a turning point in the politics of commemoration. Official Pride embraced global human rights rhetoric, corporate sponsorship, and symbolic gestures. ACT UP and grassroots activists refused that trajectory, insisting that mourning, rage, and memory remain central to their efforts. The clash revealed that by 1994, AIDS had moved from the heart of Pride to its contested margins, a shift that exposed deeper tensions over what Pride meant, who it represented, and how LGBTQ+ history would be remembered.

Notes

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, HIV Surveillance Annual Report, 2013, Table 2.

David France, How to Survive a Plague (New York: Knopf Doubleday, 2016), 354–56.

Rick Hicks, “Mile-Long Pride Flag, 1994,” Gilbert Baker Foundation; NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project.

Gilbert Baker, quoted in “Raise the Rainbow Workshop,” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project.

BC Craig, quoted in Tim Murphy, “A Timeline of HIV/AIDS Representation at New York City’s Pride March,” The Body, July 1, 2024.

Gilbert Baker at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Stonewall 25 (1994)

During the unpermitted Alternative March of Stonewall 25, Gilbert Baker stood before St. Patrick’s Cathedral, where he and fellow activists unfurled vast blocks of rainbow fabric. The cathedral, long a symbol of Catholic condemnation of LGBTQ+ lives, became the backdrop for a charged act of queer defiance. Naked bodies pressed against barricades, lovers kissed in open defiance, and chants of “Fuck you!” echoed down Fifth Avenue. In that moment, the rainbow was not a corporate brand but a living banner of grief and resistance, transforming the steps of the church into a temporary shrine that bound Stonewall’s legacy to the ongoing AIDS crisis.

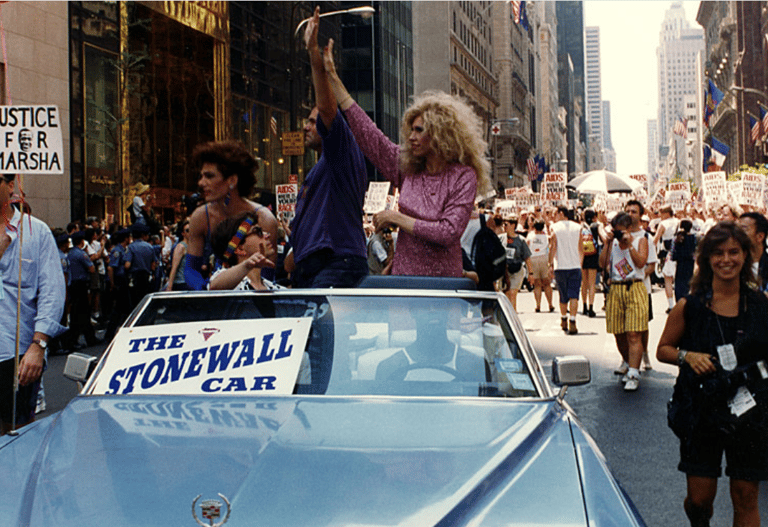

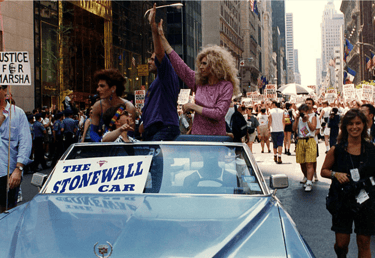

Queen Allyson Allante and the Spirit of Stonewall, 1994

In the 1994 “Spirit of Stonewall March,” Queen Allyson Allante of the Imperial QUEENS & Kings of Greater New York (IQKNY) led veterans of the 1969 uprising in a procession that retraced the original Pride route. The Cadillac they rode carried a sign reading “Justice for Marsha,” honoring Marsha P. Johnson and underscoring the unresolved struggles around gender, race, and violence in queer history. Behind them, ACT UP activists and the gleaming façade of Trump Tower formed a striking backdrop, contrasting grassroots defiance with the symbols of political neglect and corporate power. The moment captured how Stonewall 25 was both commemoration and confrontation, weaving together memory, activism, and resistance. Photograph by Willson L. Henderson of the STONEWALL Veterans' Association.. https://www.stonewallvets.org/SpiritofStonewall.htm.

(After) AIDS

By the late 1990s, the landscape of the AIDS crisis and its place within Pride had shifted dramatically. The introduction of protease inhibitors and combination therapies in 1996 transformed AIDS from a fatal illness into a manageable condition for many, at least for those with access to healthcare.¹ This medical breakthrough eased the urgency of public mourning. As fewer white, middle-class gay men were visibly dying, the tone of Pride tilted toward celebration, assimilation, and corporate sponsorship. ACT UP, once at the center of the parade, increasingly distanced itself from institutional Pride, favoring political funerals and targeted protests over what many members saw as compromised, commercialized parades.²

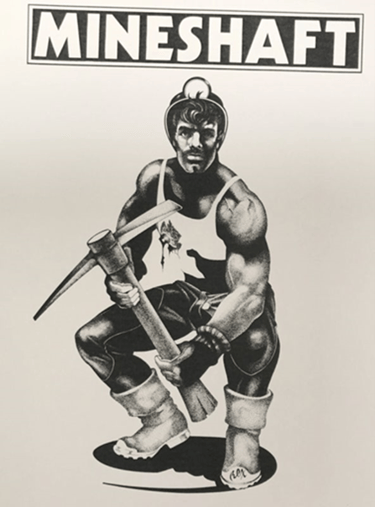

The visual identity of Pride also changed. Drag performers, RuPaul’s rising stardom, and go-go dancers on floats projected confidence, sexuality, and visibility. Yet the imagery was dominated by a particular kind of body: the shirtless, muscular, often white “Chelsea boy,” a visual shorthand for resilience and desirability (figure 28). This aesthetic echoed the hyper-masculine clone culture of the 1970s, exemplified in erotic posters for leather bars like the Mineshaft (figure 29).³ In the 1990s, these symbols of erotic vitality resurfaced as a way of reclaiming life in the face of mass death. But they also narrowed representation, pushing aside those who were visibly ill, disabled, aging, trans, or people of color, many of whom were still disproportionately affected by AIDS. The Pride parade became a stage where survival was equated with a specific kind of body, and mourning was increasingly absent from view.

The Chelsea Boy

By the 1990s, Pride parades increasingly featured the “Chelsea boy”—muscular, shirtless, and often white—as a visual emblem of queer vitality in the age of AIDS. This image projected survival and desirability but also narrowed who was seen, sidelining those most impacted by the epidemic, including people of color, women, trans people, and the visibly ill. Bob Adelman, Gay Pride Parade, New York City, 1994, photograph, Bob Adelman Estate, https://www.bobadelman.net/galleries/gay_pride_parade/.

The Mineshaft Poster

A 1970s poster for the Mineshaft depicts a rugged construction worker gripping a phallic pickaxe, merging working-class iconography with queer eroticism. This hyper-masculine aesthetic shaped later Pride imagery, where erotic power was reclaimed as defiance during the AIDS crisis, even as it reinforced narrow standards of beauty and visibility. “The Mineshaft,” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/mineshaft/.

Public rituals of grief that had once defined the 1980s—balloon releases, quilt displays, moments of silence—faded. By 1996, The New York Times covered Pride by highlighting demands for gay marriage while not mentioning AIDS at all.⁴ The shift reflected new political priorities: middle-class segments of LGBTQ life were increasingly focused on marriage equality, while organizations like GMHC, Housing Works, and the Minority AIDS Project carried the burden of remembrance and ongoing advocacy. Pride still included AIDS organizations, but corporate floats and polished branding overshadowed their visibility. The question of which grief counted, and which grief was erased, became central to Pride’s politics of memory.

Yet erasure was never complete. In 2016, after the Pulse nightclub shooting, Pride’s commemorative traditions resurfaced. Gays Against Guns staged a die-in during the parade, with marchers collapsing onto the street and veiled figures in white carrying placards bearing the names of the 49 victims (figure 30).⁵ The performance drew directly on the symbolic language of ACT UP’s die-ins and political funerals, and on the communal mourning embodied by the AIDS Memorial Quilt. It was both homage and reinvention. In the silence and stillness of bodies on the pavement, Pride momentarily returned to its role as a transitory memorial, where grief, rage, and visibility converged in public space.

The presence of long-term AIDS survivors alongside younger activists at that Pride underscored the intergenerational nature of memory. Survivors carried the weight of unresolved trauma from the epidemic, while younger participants confronted ongoing violence against LGBTQ+ communities. Their joint presence reminded all that public memory is not neutral. It must be fought for, shaped, and reclaimed.

The history of AIDS memorialization at Pride is therefore not simply a story of loss but one of continuity and reinvention. Pride has evolved from transitory acts of mourning to a stage dominated by corporate floats, yet grief resurfaces whenever crisis demands it. Each generation finds its way, through chants, ribbons, banners, or bodies in the streets, to remember and insist that the most marginalized are not forgotten. The risk of forgetting grows with spectacle, but the resources of memory remain. Pride, at its most potent, continues to be a space where celebration and resistance walk hand in hand.

Footnotes

Anthony Fauci, quoted in Lawrence K. Altman, “New AIDS Therapies Pose Difficult Choices,” New York Times, July 14, 1996, A1.

Sarah Schulman, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), 587–90.

“The Mineshaft,” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/mineshaft/.

Clyde Haberman, “At Gay Pride Parade, Push for the Right to Marry,” New York Times, June 30, 1996, Section 1, 33.

Damon Winter, “A Pride Parade of Joy and Pain,” New York Times, June 26, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2016/06/26/nyregion/a-pride-parade-of-joy-and-pain.html.