Permanent Memorials: Queer Memory in Public Space

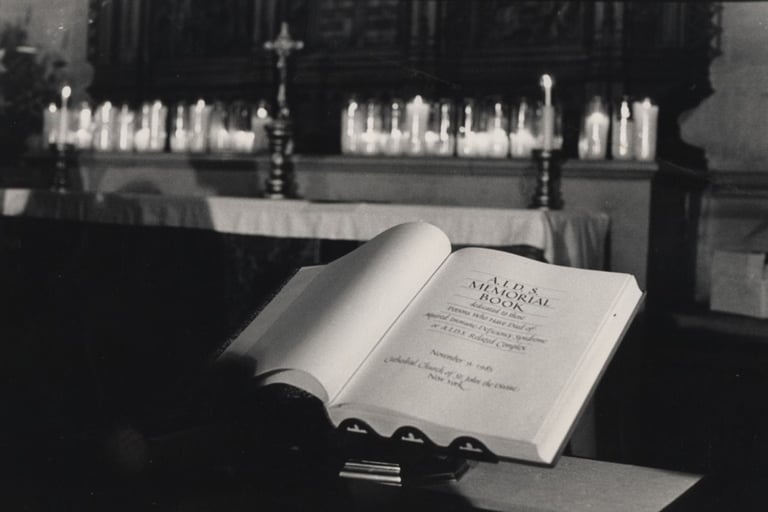

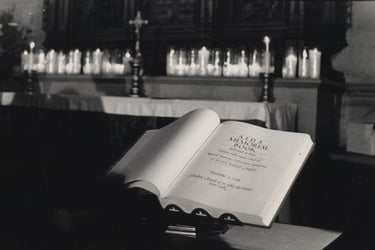

AIDS Book of Remembrance at the Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine. https://www.instagram.com/p/DDCxhktM1ij/

From Stone and Steel: The Rise of Permanent AIDS Memorials

Before the creation of a dedicated citywide AIDS memorial, permanence took root in scattered forms across New York. From sculptures and parish chapels to hospital books and public parks, communities inscribed grief into the city’s landscape in ways that were both lasting and fragile. These early memorials carried the epidemic into spaces that had long resisted recognition: churches that consecrated loss, hospitals that bore witness to the dying, and public squares that reshaped civic memory.

After years of mourning carried out through candlelight vigils, protest marches, and quilt panels, the demand for permanence could no longer be ignored. Communities devastated by loss sought memorials that would not vanish with the night or be confined within sanctuaries. Instead, they would stand in public view, inscribed into the very geography of New York City. These new monuments, built of stone, steel, and granite, transformed the landscape of the West Village and beyond, paving the way for the city’s later, unified memorial.

Yet the path to such memorials was not straightforward. As Douglas Crimp observed, the early years of AIDS were marked not only by mass death but also by an absence of public mourning, a “social silence” that denied the legitimacy of queer grief.¹ By the 1990s, activism itself shifted. As Martin Duberman argues, many LGBTQ+ advocates turned away from AIDS-centered organizing toward more moderate goals aligned with a “politics bent on respectability,” most notably the pursuit of marriage equality.² Deborah B. Gould describes the psychological cost of this transition: years of grief, rage, and caregiving had depleted survivors, producing emotional burnout and what she calls a kind of “collective amnesia.”³ Generational shifts further complicated remembrance. As Nic Weststrate and Kate McLean note, older cohorts often rooted their identity in collective struggles and historic events, such as Stonewall, while younger generations increasingly defined themselves through individualized experiences, like coming out.⁴ Together, these forces created a lull in memorialization. AIDS memory risked being overshadowed by fatigue, respectability politics, and the erasures of gentrification.

The revival of AIDS memorial efforts in the 2000s and 2010s emerged out of this silence. In Christopher Park, George Segal’s Gay Liberation Monument, conceived in 1980 but delayed for over a decade, was finally installed in 1992 and quickly reframed as a public elegy in the shadow of AIDS. At St. Vincent’s Triangle, the 2017 New York City AIDS Memorial transformed the site of the hospital that had once cared for thousands with AIDS into a civic space for remembrance. Along the Hudson River, a granite bench overlooking the piers, spaces that once thrummed with queer life and later became informal mourning grounds, offered a quieter form of reflection.

These stone and steel memorials marked a turning point. Grief was no longer ephemeral or hidden, but etched into New York’s built environment. They claim space in a city that has often erased queer presence, countering gentrification and cultural amnesia with physical reminders that cannot be folded away or dismantled. Above all, they testify to the persistence of memory in the face of silence. They are declarations that AIDS is not over, that queer loss remains inscribed in the city’s streets, parks, and waterfronts, and that remembrance continues to demand a place in New York’s future.

Notes

Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” October 51 (Winter 1989): 9–10.

Martin Duberman, Has the Gay Movement Failed? (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 16–17.

Deborah B. Gould, Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s Fight Against AIDS (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 415–20.

Nic M. Weststrate and Kate C. McLean, “The Rise and Fall of Activist Identity: Generational Shifts in Queer Identity Formation in the United States,” Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 7, no. 3 (2020): 281–92.

Gay Liberation Monument, Christopher Park

Dedicated in 1992, at the height of the AIDS epidemic, George Segal’s Gay Liberation monument took on meanings beyond Stonewall. Photo by Joseph Golden

Gay Liberation Monument: Elegy and Transformation

On June 23, 1992, George Segal’s Gay Liberation Monument was unveiled in Christopher Park, directly across from the Stonewall Inn, the site of the 1969 uprising that helped ignite modern LGBTQ+ activism.¹ The monument, consisting of two men standing in quiet intimacy and two women seated with loosely clasped hands, was modest in scale but monumental in meaning. Although Segal had completed the figures in 1980, the statue languished in storage for more than a decade. City officials hesitated to accept a public artwork that depicted same-sex affection. At the same time, Christopher Park, long a refuge for queer youth and a site of resistance, was deemed too provocative during an era of conservatism and backlash.² A brief installation at Stanford University in 1984 ended in repeated vandalism, underscoring how contested public expressions of queer intimacy remained, even in seemingly liberal spaces.³

By the time the monument was installed in New York, the AIDS crisis had reshaped its meaning. Originally intended as a celebration of ordinary presence, the figures became a public elegy. The men’s gesture of touch echoed the final embraces of lovers at hospital bedsides. At the same time, the women’s quiet solidarity embodied the indispensable, often invisible labor of lesbian caregivers who sustained their communities when institutions turned away.⁴

Situated in the West Village, the monument stood amid a neighborhood profoundly altered by loss. Beloved queer spaces like the Paradise Garage and the Saint had closed,⁵ while bathhouses such as St. Mark’s and Mt. Morris were shuttered in the name of public health.⁶ Even Christopher’s End, once an after-hours club notorious for police raids and activist “zaps” by the Gay Activists Alliance, was reborn as Bailey-Holt House in 1986, the first permanent residence for people with AIDS.⁷ As tenants died, rent-controlled apartments were reclaimed, and gentrification accelerated, erasing much of the neighborhood’s queer geography.⁸

In this context, the Gay Liberation Monument became more than a symbolic representation of love; it became a tangible embodiment of the community's collective identity. It marked the transformation of Christopher Park itself into a site layered with memory: the birthplace of Stonewall, a ground for ACT UP demonstrations, and a gathering space for AIDS vigils and memorials.⁹ Though no names are etched into Segal’s bronze figures, their gestures carry the weight of those who fought, loved, and died. From here, Christopher Street led westward, where annual candlelight vigils carried mourners in processions of grief and defiance. Along the way stood St. Veronica’s Church, whose hospice and memorial services embodied communities of care when hospitals and institutions turned people away. Christopher Street was also lined with gay and lesbian businesses that flourished during the 1970s but were devastated in the 1980s by AIDS, violence, and gentrification, erasing much of the street’s queer geography. At the river’s edge, where mourners gathered with candles, flowers, and ashes, the city finally dedicated its first permanent AIDS memorial in 2008. Together, these sites form a procession from liberation to care, from joy to grief, and from ephemeral vigils to enduring monuments, anchoring queer memory in a landscape where celebration, mourning, and survival remain inseparably bound.

Footnotes

“Dedication of the Gay Liberation Monument, 1992,” NYC Parks, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/christopher-park/monuments/572.

Christopher Reed, Art and Homosexuality: A History of Ideas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 243–44.

Marita Sturken, Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 197.

Sarah Schulman, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), 76–77.

Tim Lawrence, Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980–1983 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 325–27.

Ronald Bayer, Private Acts, Social Consequences: AIDS and the Politics of Public Health (New York: Free Press, 1989), 109–11.

“Bailey-Holt House,” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/bailey-holt-house.

David France, How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS (New York: Knopf, 2016), 243.

Jim Hubbard, dir., Elegy in the Streets, 1989; ACT UP Oral History Project, https://actuporalhistory.org.

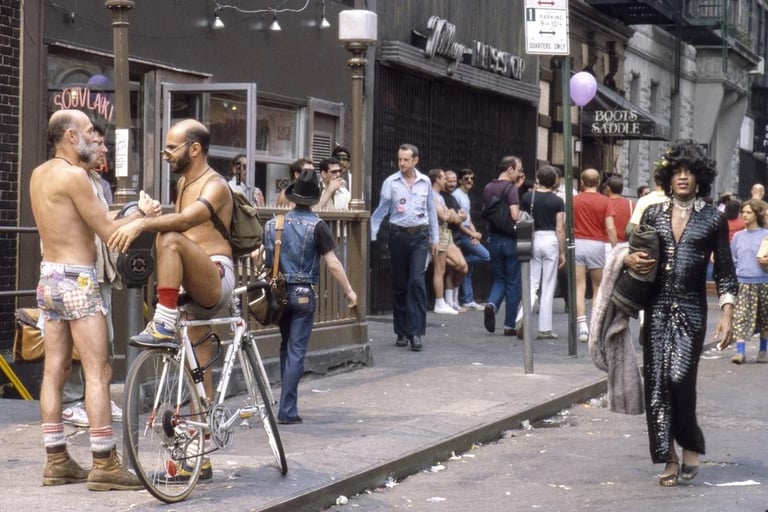

Christopher Street at the southwest corner of 7th Avenue, outside Village Cigars, during the 1982 Pride March. Marsha P. Johnson stands at the intersection, a reminder that the activism embodied in Segal’s monument flowed into the street itself. Behind her, the gay bar Boots & Saddle anchors the block—a neighborhood dive that opened in the wake of the Stonewall riots, when gay businesses first began to emerge more visibly along Christopher Street. For decades, Boots & Saddle was part of the cultural fabric of the Village until its closure in 2018, another casualty of rising rents and the gentrification of queer space. Barbara Alper, Getty Images.

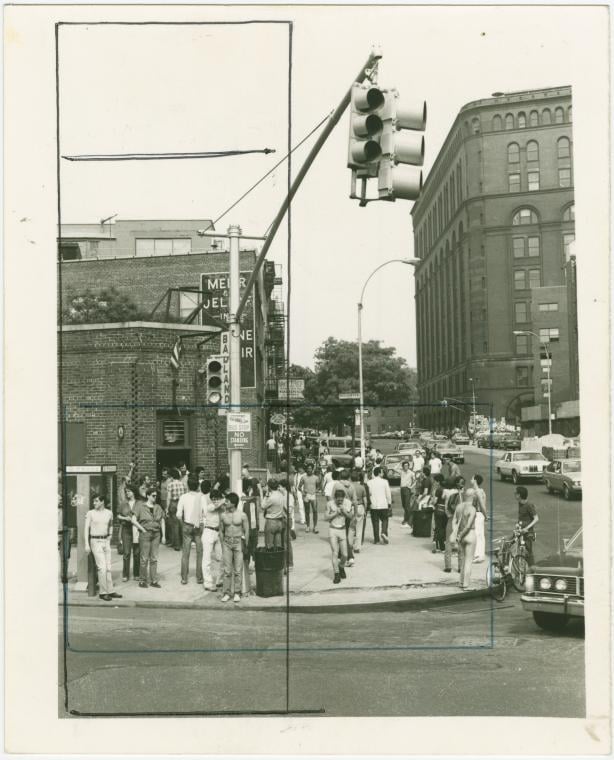

Christopher Street at West Street, c. 1980s. The AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s devastated Christopher Street’s identity as a thriving gay thoroughfare, leaving bars like Badlands (388–390 West Street) emptied by loss. Located within the Weehawken Street Historic District, where six of fourteen buildings housed gay bars since the 1970s, the site reflects both the vitality of queer nightlife and the void created by AIDS. Just across the street, the Hudson River piers became places of informal mourning, where candles, flowers, and ashes marked grief in the absence of official recognition. In this geography, nightlife and memorialization are intertwined, foreshadowing the later creation of permanent AIDS memorials in the West Village. Photo by Richard Wandel, The New York Public Library.

“Weehawken Street Historic District Designation Report,” Village Preservation, June 2, 2006, 11, https://vparchive.gvshp.org/_gvshp/pdf/PDFs/weehawkenstreet-report.pdf#page=11.

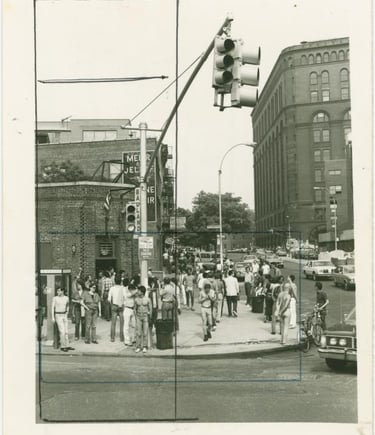

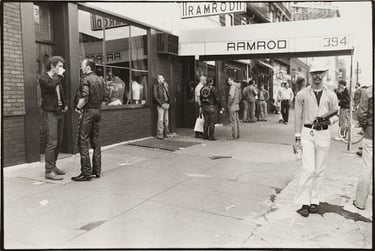

The Ramrod bar, West Street at Weehawken, c. 1978. Emerging in the 1950s, leather bars like the Ramrod, the Eagle, and the Mineshaft offered gay men a space to explore fetishism, BDSM, and sexual freedom. Dark, smokey, and unapologetically erotic, these bars flourished in industrial corners of the city even as they were targeted by police and condemned by the public. Artists such as Tom of Finland drew inspiration from their culture, which epitomized both defiance and visibility.

On the night of November 19, 1980, that freedom was shattered when gunman Ronald K. Crumpley opened fire outside the Ramrod, killing two men and wounding several others in what the New York Times called the “West Street Massacre.” In response, more than 2,000 people joined a silent, candlelit march to the piers. The vigil transformed grief into defiance and foreshadowed the AIDS memorial practices that followed—candlelight vigils, political funerals, and acts of public mourning that refused to let queer lives be erased.

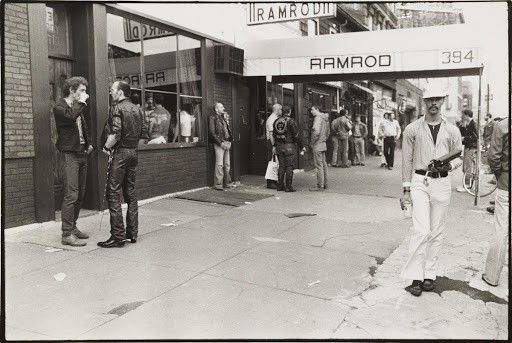

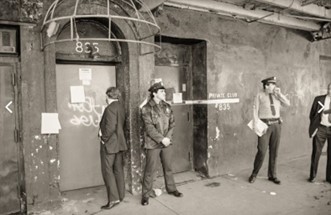

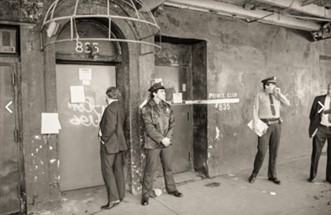

The closing of the Mineshaft, an after-hours sex club and filming location of the movie Cruising (1980). Nov. 7th, 1985. The decision to close venues like the Mine Shaft and St. Marks Baths, characterized by the media as symbols of unsafe behavior, sparked public debate about civil liberties versus public health. Photo by Rich Maiman. NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/mineshaft/

The Village AIDS Memorial at St. Veronica’s Church

As Christopher Street’s queer culture was devastated by AIDS, St. Veronica’s Church at 153 Christopher Street became an unlikely anchor of mourning and memory. Built in 1903 to serve Irish dockworkers, the parish by the late twentieth century found itself at the heart of Pride celebrations, candlelight vigils, and the struggle to reckon with loss.¹

Built in 1903 to serve Irish longshoremen and their families, St. Veronica’s Church at 153 Christopher Street reflected the working-class, immigrant life of the West Village. By the 1970s, its congregation mirrored the neighborhood’s changing demographics, welcoming Puerto Rican families and openly gay parishioners at the heart of New York’s queer community.

St. Veronica’s Church: From Vigil to Memorial

At the height of the AIDS crisis, Christopher Street’s landscape of bars, clubs, and gathering places was rapidly disappearing. Yet just steps from the Stonewall Inn and the Hudson River waterfront, St. Veronica’s Church became an unexpected anchor of grief and resilience. Founded in the 1880s to serve immigrant dockworkers, the modest brick parish emerged a century later as one of the few Catholic institutions in New York willing to stand with the LGBTQ+ community.¹

By 1985, its rectory housed one of Manhattan’s first AIDS hospice programs, offering care when hospitals often turned people with AIDS away.² The front steps soon became the site of annual candlelight vigils—rituals that blended Catholic forms like candles and hymns with the political urgency of protest. These gatherings declared that queer lives were grievable and sacred, transforming the church into a space of mourning, solidarity, and resistance.³

In 1992, St. Veronica’s dedicated the Village AIDS Memorial in its choir loft: 580 engraved plaques honoring New Yorkers lost to AIDS.⁴ Like the Books of Remembrance at St. Clare’s Hospital and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, the plaques created a sacred site where names could be spoken and remembered at a time when mainstream culture erased them.⁵ In the basement, funds from weekly Gay Bingo nights supported “The Meeting Place,” a refuge for Twelve-Step meetings and community gatherings that sustained many through the epidemic.⁶

Despite internal tensions and eventual closure in 2017, St. Veronica’s legacy endures. In 2022, the Village AIDS Memorial was permanently relocated to the Church of St. Francis Xavier on West 16th Street, ensuring public access to the plaques and safeguarding this history for future generations.⁷ Today, the memorial continues to honor lives lost, affirming that queer grief belongs within sacred space and remains visible in the city’s cultural memory.

Footnotes

“Village AIDS Memorial,” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/village-aids-memorial-st-veronicas-church/.

Daniel Baxter, The Least of These My Brethren: A Doctor’s Story of Hope and Miracles on an Inner-City AIDS Ward (New York: Kensington Publishing, 2017).

Stefan Schwarzkopf, Sine Nørholm Just, and Jannick Friis Christensen, “Stairway to Heaven: LGBTQ+ Gatherings as Civil-Religious Rituals,” Society 61, no. 3 (2024): 322–32.

David Dunlap, “A Place in Church for Mourning AIDS Victims,” New York Times, December 1, 1992, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/12/01/nyregion/a-place-in-church-for-mourning-aids-victims.html.

National AIDS Memorial, “Book of Remembrance,” accessed February 2025, https://www.aidsmemorial.org; Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine, “National AIDS Memorial & Keith Haring Altar,” accessed February 2025, https://www.stjohndivine.org.

Michael J. O’Loughlin, “Hidden in a New York Choir Loft, an Early AIDS Memorial Faces an Uncertain Future,” America Magazine, July 28, 2017, https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2017/07/28/hidden-new-york-choir-loft-early-aids-memorial-faces-uncertain-future.

Armando Machado, “The Church of St. Francis Xavier Installs AIDS Memorial,” The Good Newsroom, December 5, 2022, https://thegoodnewsroom.org/the-church-of-st-francis-xavier-installs-aids-memorial/.

The Village AIDS Memorial at the choir loft of St. Veronica's Roman Catholic Church, 2017. Photo by Michael O'Loughlin. https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2017/07/28/hidden-new-york-choir-loft-early-aids-memorial-faces-uncertain-future/

Village AIDS Memorial plaques at the Church of St. Xavier. Housed initially at St. Veronica’s Church, the Village AIDS Memorial plaques were relocated here after its closure, linking Xavier’s long history of faith and activism during the AIDS crisis to the present. In 1986, Xavier became the first Catholic parish in the United States to hold a memorial service for a man who had died of AIDS, and today it remains home to active LGBTQ ministries and the memory of those lost.

AIDS Memorials on the Waterfront: Hudson River Park and Battery Park

At the western edge of Christopher Street, where the pavement meets the Hudson River, the geography of queer New York gave way to both liberation and loss. For decades, the Christopher Street Piers had been a sanctuary for queer and trans people, especially youth marginalized by race, class, or gender identity. Here, figures such as Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera forged chosen families and mutual aid networks, while Black and Latinx youth carved out spaces of kinship and performance.¹ The piers became stages for intimacy and expression, immortalized in Jennie Livingston’s documentary Paris Is Burning, which captured their role in nurturing the resilience of ballroom culture.²

The AIDS epidemic transformed this ground of joy into a terrain of mourning. Lovers scattered ashes into the river, candlelight vigils traced their way down Christopher Street. They ended in silence at the water’s edge, and acts of public remembrance layered grief onto a geography already dense with meaning.³ Yet by the mid-1990s, redevelopment under the Hudson River Park Conservancy imposed curfews, fences, and park police. “In 1990, we had five different piers, and now we have half of one,” a protester declared in 1997, as activists condemned what they saw as a deliberate erasure of public queer life.⁴ The piers, once spaces of freedom, were remade as contested ground, even as AIDS and gentrification hollowed out the neighborhood’s queer core.

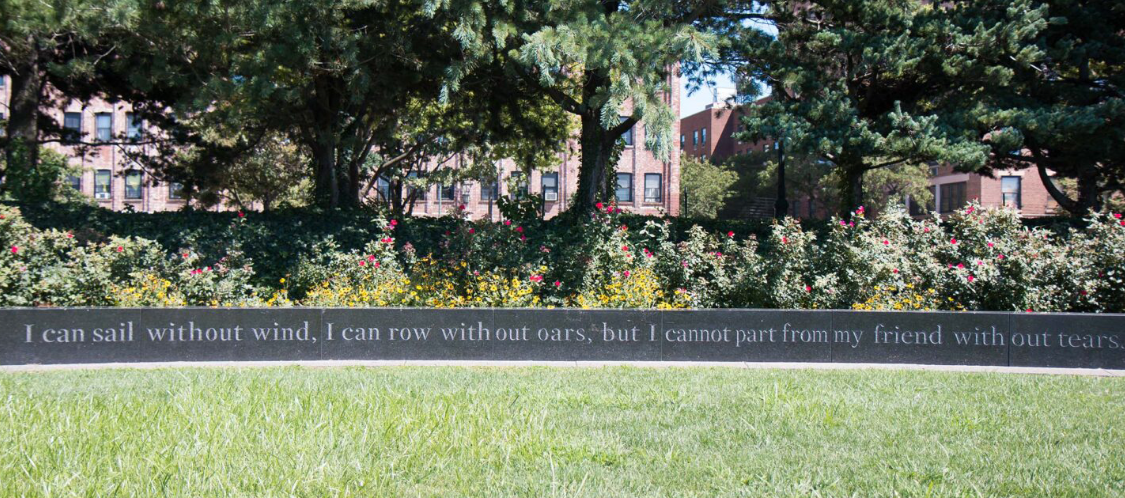

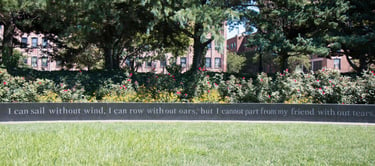

It was within this transformed landscape that the AIDS Memorial at Hudson River Park was dedicated in 2008 at Pier 49. The polished granite boulder, inscribed with the words, “I can sail without wind, I can row without oars, but I cannot part from my friend,” faces the Hudson River that had borne witness to decades of queer presence.⁵ The memorial draws its power from place: it recalls the waterfront’s role as a site of liberation, pleasure, and resistance, even as it anchors grief in stone. By situating AIDS remembrance in a geography once threatened with erasure, the memorial asserts that queer loss belongs to the civic memory of the city.

Sunbathers on the Hudson River piers near Christopher Street, c. 1970s. Before the epidemic, the piers symbolized queer freedom and intimacy; by the 1980s, the same waterfront became a place of grief and memorialization as the community gathered for vigils and farewells.

The AIDS Memorial at Hudson River Park, dedicated in 2008 at West Street and Bank Street. Marking a site where countless vigils were held and ashes of the dead were scattered, the granite benches and inscription honor those lost to AIDS and root remembrance in the very geography of the West Village waterfront.

By contrast, the Hope Garden in Battery Park, dedicated on May 14, 1992, reflected an earlier and more fragile form of AIDS memorialization.⁶ Conceived as a living landscape rather than a monument of stone, the garden was notable for its absence of names. This was intentional: its designers sought to create a contemplative public space that could symbolize both remembrance and hope, offering solace without the permanence of engraved identities. On World AIDS Day in 1993, journalist Laura King observed that such sites were not only spaces of mourning but also urgent calls for awareness of an epidemic still raging.⁷

Yet the Hope Garden’s impact was complicated by its setting. After 9/11, The Sphere, a massive bronze sculpture salvaged from the ruins of the World Trade Center, was placed within the garden and visually dominated the space.⁸ While a potent memorial in its own right, The Sphere overshadowed the AIDS dedication and revealed how queer grief could be easily eclipsed in New York’s crowded commemorative landscape. Only after the sculpture was moved to Liberty Park in 2017 did the Hope Garden begin to reclaim its intended role as an AIDS memorial.

Hope Garden, Battery Park. Conceived as one of New York’s earliest AIDS memorials, the garden offered a contemplative green space without names, symbolizing remembrance and hope at the height of the epidemic. Photo courtesy of NYC Department of Parks & Recreation.

Together, these New York memorials capture the precariousness and persistence of AIDS remembrance in public space. The Hudson River Park memorial ties memory to the reclaimed geography of Christopher Street and the piers, ensuring that queer histories of joy and grief are visibly inscribed along the waterfront. The Hope Garden, by contrast, shows how such memory could be eclipsed, its fragility revealing the challenges of sustaining queer remembrance in contested civic terrain.

These tensions resonate with the National AIDS Memorial Grove in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, dedicated in 1996.⁹ Like the Hope Garden, the Grove was conceived as a living memorial of trees and pathways rather than stone. Still, unlike the Battery Park site, it achieved national recognition when Congress designated it the United States’ official AIDS memorial that same year.¹⁰ Its permanence reflects a more institutionalized model of remembrance, in contrast to New York’s more precarious, locally rooted commemorative practices. Read together, these memorials show how AIDS memory has been unevenly inscribed into public space—sometimes central, sometimes fragile, but always shaped by the geography in which it resides.

Footnotes

“Christopher Street Piers,” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, accessed May 1, 2025, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/christopher-street-piers/.

Jennie Livingston, dir., Paris Is Burning (New York: Miramax, 1990).

Jim Hubbard, dir., Elegy in the Streets (1989); Gay Cable Network, Pride Parade and Christopher Street Festival Coverage, June 1988, Gay Cable Network Archives, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University.

David W. Dunlap, “For Homeless With AIDS, a New Home,” New York Times, January 5, 1987, https://www.nytimes.com/1987/01/05/nyregion/for-homeless-with-aids-a-new-home.html.

Hudson River Park Trust, “AIDS Memorial at Pier 49,” Hudson River Park, accessed September 19, 2025, https://hudsonriverpark.org/the-park/parks-river/aids-memorial/.

“Hope Garden at Battery Park,” AIDS Memorial Info, accessed September 19, 2025, https://aidsmemorial.info/memorial/id%3D183/hope_garden_at_battery_park.html.

Laura King, “World AIDS Day Urges More Public Awareness,” Chicago Sun-Times, December 1, 1993, archived October 21, 2012.

Battery Park Conservancy, “The Sphere,” accessed September 19, 2025.

National AIDS Memorial, “History of the National AIDS Memorial Grove,” accessed September 19, 2025, https://www.aidsmemorial.org/grove.

United States Congress, Public Law 104-333, November 12, 1996, designating the AIDS Memorial Grove as the nation’s official AIDS memorial.

Consecrated Loss: Books of Remembrance at St. John the Divine and St. Clare’s

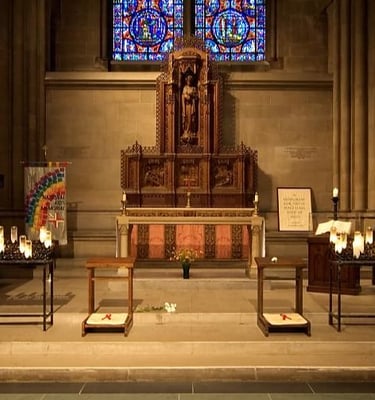

If St. Veronica’s Church and the Village AIDS Memorial demonstrated how parish communities sanctified grief in Greenwich Village, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine carried this consecration onto a monumental scale. Rising over Amsterdam Avenue at 112th Street in Morningside Heights, St. John’s is the largest Gothic cathedral in the world, its nave stretching nearly two football fields in length and its vaults soaring 124 feet high. Within this immense sanctuary, on November 9, 1985, the Cathedral inaugurated the National AIDS Memorial Book of Remembrance.¹

AIDS Memorial in the Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine. Photo by Joseph Golden

The book was not hidden in a side chapel but installed in the Medical Bay of the Cathedral’s nave, a space set aside for healing ministries and pastoral care. Visitors walking the length of the vast central aisle would pass through the nave toward this alcove, where the Book of Remembrance rested on a stand and could be opened to reveal the inscribed names of the dead. The choice of location mattered: it placed AIDS memory within the very heart of the Cathedral’s liturgical life, in a space associated with prayer, anointing, and the tending of bodies. To inscribe names here was to assert that lives lost to AIDS were not profane or unworthy, but belonged fully within the Cathedral’s spiritual and architectural fabric.

One of Haring's last works, the triptych is made of cast bronze plated in white gold. The subject is Haring's personal interpretation of the Christian Apocalypse, with love ultimately triumphing. Haring's funeral was held in St. John the Divine.

Photo by Doug Blanchard https://www.aidsmemorial.info/contribution/id=777/mid=3/national_aids_memorial_at_cathedral_of_st_john_the_devine.html

The Cathedral’s memorial presence grew in the years that followed. In 1990, only weeks before his death, Keith Haring completed "Life of Christ," a monumental triptych in bronze and white gold leaf.² Installed as an altarpiece in the Chapel of St. Saviour, just off the north transept, the work measures five by eight feet and weighs nearly 600 pounds. Its imagery, Christ flanked by angels and human figures carved in Haring’s energetic line, transforms the idiom of modern art into a religious icon. The piece became both Haring’s final testimony and one of the Cathedral’s most enduring AIDS memorials, standing where worshippers gather for prayer and reflection.

The Cathedral also hosted the AIDS Memorial Quilt.³ During World AIDS Day services and AIDS Walk commemorations, panels were unfurled in the nave, beneath the Cathedral’s immense vaults. In 2018, three Quilt panels honoring members of the Cathedral community were displayed, while names were read aloud and Lavender Light, the Black and People of All Colors Lesbian and Gay Gospel Choir, sang in tribute. Within this space, private grief resonated in public rituals, and the quilt’s fragility was held inside the grandeur of Gothic permanence.

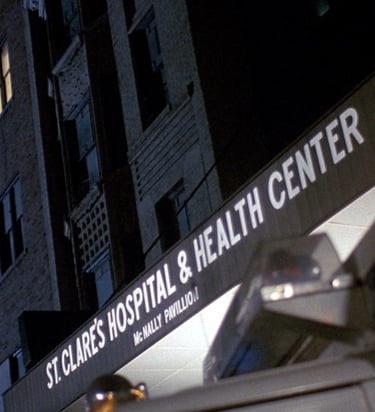

The main entrance to St. Clare's Hospital and Health Center, ca. 1986.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St._Clare%27s_Hospital_and_Health_Center.png

If St. John’s Cathedral embodied permanence —stone, bronze, parchment —St. Clare’s Hospital revealed the fragility of remembrance outside such enduring institutions. Located at 415 West 51st Street in Hell’s Kitchen, St. Clare’s was founded in the 1930s by the Franciscan Sisters of the Poor to serve immigrant and working-class New Yorkers. Long underfunded and often described as decrepit, it was precisely this marginality that allowed it to take moral and medical risks others would not. In 1985, St. Clare’s opened one of the city’s first dedicated AIDS units, the Spellman Center for HIV-Related Diseases, and began keeping its own Book of Remembrance in the hospital chapel, a modest yet profound attempt at permanence amid uncertainty.

Today, both the chapel and the book have been lost, their disappearance underscoring how easily histories rooted in care, faith, and community can vanish when not safeguarded. The absence of these artifacts is itself a poignant reminder of neglect, underscoring the importance of preservation, archival, architectural, and digital efforts in sustaining AIDS memory in New York City.⁴ Quarterly memorial services in the hospital’s small chapel gave dignity to lives society had cast aside. Each began with an organ prelude, a welcome from Sister Pascal, and a meditative reading. A staff-led procession opened the Book and lit a candle before the Reading of Names, as many as fifty patients who had died in the prior three months. Dr. Daniel Baxter recalled:

“Many of the names read aloud—Jose, Yolanda, Juan, Maria, and Hector—belonged to people who had been unwanted or forgotten, that is, until they came to St. Clare’s and its Spellman Center.”⁴

These were women, children, sex workers, immigrants, drug users, and the unhoused: people rarely acknowledged in newspapers or official records, yet remembered here with reverence. Unlike Hart Island, where thousands of AIDS victims were buried anonymously in mass graves, St. Clare’s insisted that every life be named.

“Some of the people I took care of had spent much of their lives in prison, on the streets, or in shooting galleries. And yet, in their dying, they showed more dignity, more grace, and more courage than many of the so-called respectable people I had known in Washington, DC. That’s what St. Clare’s taught me—that humanity isn’t measured by where you’ve been, but by how you face suffering and how others bear witness to it.”⁵

Unlike Hart Island, where thousands of AIDS victims were buried anonymously, St. Clare’s made sure no one died unnamed. But the hospital closed in 2007 amid a financial crisis, and the fate of its Book of Remembrance remains uncertain.⁶ Its possible disappearance underscores how fragile community-based memorials could be, even when they carried profound significance for those they honored.

Taken together, St. John the Divine and St. Clare’s Hospital illustrate two poles of AIDS remembrance in New York. The Cathedral, with its vast Gothic presence, conferred permanence and institutional authority: a book enshrined in a nave, a bronze altarpiece, fabric displayed beneath vaults meant to last centuries. St. Clare’s, by contrast, offered dignity to the most marginalized, but its memorial practices were tied to a vulnerable institution whose records may now be gone. One endures in stone; the other survives in memory. Both remind us that remembrance is not only about architecture or archives—it is about whose names are preserved, whose are lost, and how communities insist on bearing witness.

Notes

“National AIDS Memorial at Cathedral of St. John the Divine,” AIDS Memorial, accessed April 17, 2025, https://www.aidsmemorial.info/contribution/id=778/mid=1/national_aids_memorial_at_cathedral_of_st_john_the_devine.htm.

Haring Foundation, “Life of Christ,” Haring Foundation Blog, 2012, https://foundationblog.haring.com/news/684.

Cathedral of St. John the Divine, “World AIDS Day Commemoration,” November 30, 2018, https://www.stjohndivine.org/calendar/13422/world-aids-day-commemoration.

Daniel Baxter, The Least of These My Brethren: A Doctor’s Story of Hope and Miracles on an Inner-City AIDS Ward (New York: Random House, 1997), 156–57.

Daniel Baxter, quoted in John-Manuel Andriote, “One Life at a Time: A Conversation with Dr. Daniel Baxter,” Los Angeles Review of Books, December 1, 2020, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/one-life-at-a-time-a-conversation-with-dr-daniel-baxter/.

David W. Dunlap, “St. Clare’s Hospital to Close Its Doors,” New York Times, February 2, 2007.

Share Your Story

Your voice matters. If you have memories, photographs, or reflections connected to the AIDS crisis in New York City, we invite you to share them. Together we can preserve these histories and ensure they are never forgotten.