ACT UP and the Politics of Mourning

ACT UP stages a die-in at St. Patrick’s Cathedral during the Pride Parade in 1991. Photograph by C. L. Litt. Courtesy of T.L. Litt Photography, https://www.tllittphotography.com/archive/.

ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), founded in New York in 1987, quickly became one of the most visible and influential activist groups of the epidemic. Known for its confrontational tactics —die-ins, political funerals, disruptive marches, and graphic visual culture —ACT UP is often remembered primarily for its militancy. Yet memorialization was never far from its work. The group’s relationship to memorial practices was both critical and creative, sometimes skeptical of traditional forms of mourning, but also adept at transforming them into acts of resistance.

From the outset, ACT UP members wrestled with the role of public grief. Candlelight vigils, which had been central to community mourning since the early 1980s, offered solace and visibility at a time when churches and newspapers often denied recognition to people with AIDS. These gatherings, held most prominently in Sheridan Square and along Christopher Street, reclaimed public space with candles, signs, photographs, and songs. But for many in ACT UP, vigils could feel too quiet, too easily absorbed into indifference. Bradley Anderson Ball, a founding member and the group’s first recording secretary, confessed after a 1987 vigil in Sheridan Square: “I’ve spent this weekend handing out leaflets... and now I find out we’re singing for our lives… Oh God, I’m tired and angry.”¹ A year later, he reinforced his critique, writing, “We have spent many years mourning and bereaving and have developed that into a high art... [But] massive sectors of society are dying, and no one seems to care.”²

Others echoed this frustration. Jeanne Kracher of DAGMAR and C-FAR recalled activists asking during marches, “Why aren’t we saying something?”³ ACT UP member Darrell Gordon condemned what he saw as defeatism when vigils failed to challenge government neglect or the pharmaceutical industry.⁴ As Deborah B. Gould notes, “the gentle laments of traditional vigils often masked a seething anger, a frustration born of being continuously marginalized and forgotten.”⁵

Still, ACT UP did not reject vigils outright. Instead, they redefined them. Jim Hubbard’s 1988 footage of a Sheridan Square vigil shows ACT UP members carrying Quilt panels and banners, fusing grief with protest. Silence itself became a weapon, punctuated by chants, whistles, and die-ins. Larry Kramer famously questioned why “the huge numbers that show up for Candlelight Marches, all duly recorded for the television cameras,” failed to generate lasting political pressure.⁶ Yet he himself spoke at early vigils, including the May 1983 Sheridan Square demonstration at Federal Hall, using the platform to galvanize outrage.⁷ Similarly, Douglas Crimp warned that mourning could risk reinforcing passivity if not paired with mobilization.⁸ But as Sarah Schulman has argued, ACT UP “used every cultural form available to make AIDS visible—funerals, vigils, marches, die-ins, and parades alike.”⁹

In this way, ACT UP’s memorial practices reveal a central tension: mourning alone was never enough, yet grief was indispensable. Vigils provided the form, ACT UP provided the urgency. Out of that fusion came political funerals, die-ins, and dramatic interruptions of Pride that brought the epidemic into full public view.

Footnotes

Bradley Ball, quoted in David Anger, “On ACT UP,” ARTPAPER, October 1988, ACT UP/New York Records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library.

Bradley Ball, ibid.

Jeanne Kracher, quoted in Deborah B. Gould, Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s Fight against AIDS (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), Kindle Locations 2744–2753.

Darrell Gordon, quoted in Gould, Moving Politics, Kindle Locations 2744–2753.

Gould, Moving Politics, Kindle Locations 2736–2742.

Larry Kramer, remarks at 1983 candlelight vigil, quoted in Gould, Moving Politics, Kindle Locations 2742–2744.

Julius Genachowski, “1,500 Mourn Deaths of Those with AIDS,” Columbia Daily Spectator, May 3, 1983.

Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” in Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002), 133–150.

Sarah Schulman, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), 76–77.

Jim Hubbard, Candlelight Vigil, Christopher Street, New York, c. 1988, Screenshot of ACT UP Members Carrying the AIDS Quilt during the Fighting For Our Lives Candlelight Vigil. Unedited footage. Accessed May 3, 2025. https://www.jimhubbardfilms.com/unedited-footage/candlelight-vigil-christopher-street-new-york-c-1988

ACT UP and Pride: Mourning as Militancy

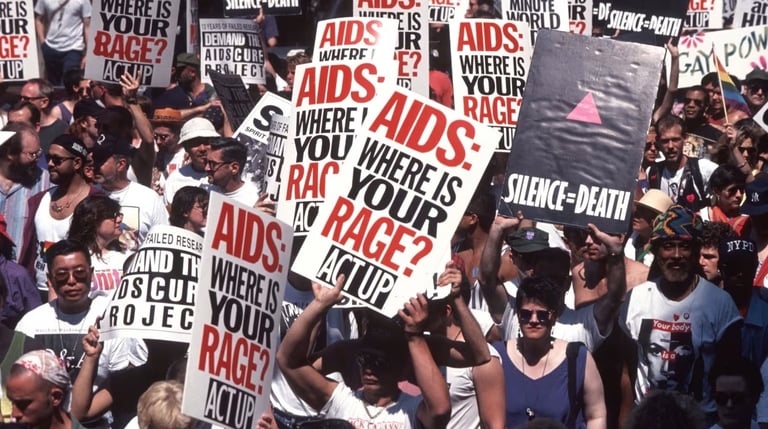

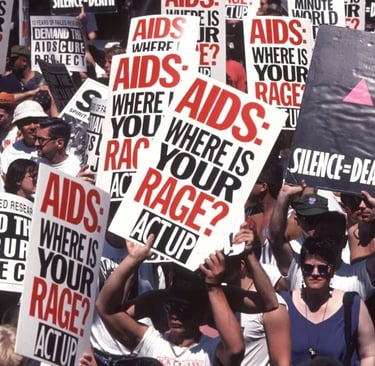

ACT UP’s first participation in the 1987 Pride Parade clarified its strategy. Marchers chanted “ACT UP! FIGHT BACK! FIGHT AIDS!” and carried stark, confrontational signs that cut through the celebratory atmosphere with a jolt of urgency. This was not a rejection of Pride’s spirit but a reimagining of it: protest became performance, rage became ritual, and mourning became public demand. Through die-ins, political funerals, black clothing, and provocative graphics, ACT UP linked grief, resistance, and celebration. Their presence made it impossible to compartmentalize AIDS as a private tragedy or niche concern.¹

Float by ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) at the Gay Pride March, New York City, June 28, 1987. Photo by Donna Binder.

One of ACT UP’s most searing interventions came in the form of a float designed to resemble a concentration camp—a chilling indictment of the Reagan administration’s deadly inaction. Hastily built in a day at artist Mark Simon’s Williamsburg studio, the float used scrap wood, plastic sheeting, and wire mesh. Members staged a haunting tableau: some, in masks and gloves, acted as guards; others, including people living with AIDS, sat motionless as prisoners. One activist wore a Ronald Reagan mask, turning the president into an emblem of cruelty.² The float fused theatricality with grief, echoing the disruptive spectacle of early Gay Liberation while adapting it to the urgency of mass death.

Theatricality became central to ACT UP’s protest strategy. A massive die-in on Fifth Avenue during Pride saw marchers collapse in silence, their bodies haunting reminders of the epidemic’s toll. “Exactly at noon,” Avram Finkelstein recalled, “we staged a die-in... we stole Fifth Avenue from the city for our own purposes and needs and fury.”³ Pride became a proving ground where mourning itself became direct action.

Silence, too, was redefined. By 1987, the Pride Parade’s Moment of Silence had become tradition, honoring those lost to AIDS. For ACT UP, silence could never be passive. The slogan “Silence = Death” crystallized their position: remembrance without resistance risked complicity. They wielded silence strategically, in die-ins, in vigils, where stillness itself became a form of confrontation. But they also punctured the silence with air horns, chants, and banners, refusing to be erased. As Sarah Schulman notes, ACT UP used every cultural form available—vigils, funerals, marches, die-ins, parades—to make AIDS visible.⁴

Gran Fury, ACT UP’s “unofficial propaganda ministry,” extended this strategy into visual culture. Their bold graphics, including “You’ve Got Blood on Your Hands,” “Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do,” appeared on posters, stickers, billboards, and in Pride marches.⁵ These were not aesthetic flourishes but tools of confrontation, forcing spectators to reckon with AIDS as a political crisis, not private grief.

Yet ACT UP’s interventions did not extinguish Pride’s celebratory spirit. Activists mixed grief with eroticism, marching with banners such as “Men: Use Condoms or Beat It!” They mourned while dancing, kissing, and affirming queer survival. As Douglas Crimp argued in “Mourning and Militancy,” grief and pleasure were not opposites but intertwined.⁶ To be visibly, sensually queer in the midst of a devastating epidemic was itself a memorial act: a refusal of erasure, a defiant insistence on life.

Through these tactics, ACT UP redefined Pride as a stage where mourning, militancy, and joy coexisted. The parade became not only a celebration but a confrontation, not only a remembrance but a resistance.

Footnotes

Sarah Schulman, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), 76–77.

Avram Finkelstein, quoted in “Gran Fury Paintings, Bio, Ideas,” The Art Story, accessed May 5, 2025, https://www.theartstory.org/artist/gran-fury/.

Avram Finkelstein, quoted in Murphy, “A Timeline of HIV/AIDS Representation at New York City’s Pride March.”

Schulman, Let the Record Show, 76–77.

The Art Story, “Gran Fury Paintings, Bio, Ideas.”

Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” October 51 (Winter 1989): 3–18; see also Martin Duberman, Has the Gay Movement Failed? (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 16–17; Deborah B. Gould, Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s Fight Against AIDS (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 415–420.

Mayor Ed Koch unveils the new Stonewall Place sign at the 1989 dedication ceremony. Gay Cable Network, Rally at Center/Stonewall Place, video, Gay Cable Network Archives, MSS.231, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University, 1989. https://findingaids.library.nyu.edu/fales/mss_231/video/9ghx3stm/

Protesters hold signs reading “Killed by Koch” during the Stonewall Place dedication ceremony, 1989. Gay Cable Network, Rally at Center/Stonewall Place, video, Gay Cable Network Archives, MSS.231, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University, 1989. https://findingaids.library.nyu.edu/fales/mss_231/video/9ghx3stm/

Memorialization Interrupted: 1989–1996

On June 6, 1989, the City of New York renamed the blocks around Christopher Park as Stonewall Place, thereby enshrining the 1969 uprising in the city’s official geography.¹ This gesture of memorialization sought to canonize queer resistance in the urban landscape, yet it unfolded in the shadow of the AIDS epidemic. For ACT UP, the dedication was an occasion not for celebration but confrontation. When Mayor Ed Koch rose to speak, activists interrupted, chanting against his record of neglect during the epidemic, until he abandoned the stage.² Gay Cable Network footage captured a divided community: some praised ACT UP for embodying the spirit of defiance that Stonewall had inspired. In contrast, others lamented that AIDS protests were “intruding” on a day meant for unity and pride.³ The tension revealed the fragile line between memorial and memory, between official commemoration and the realities of mass death.

On the eve of the 1989 Pride Parade, more than 1,500 activists marched without a permit from Sheridan Square to Central Park, denouncing what they saw as the depoliticization of Pride. They chanted “We Say Fight Back—They Say Get Back!” and staged a kiss-in at 34th Street, reclaiming public space through acts of mourning and militant visibility.⁴ Adrian Milton, an ACT UP member, explained the choice bluntly: “We thought it would be better to make a political statement than to have a parade. We thought it was more important to let people know that the gay-rights movement still faces many problems and has a long way to go.”⁵ Milton contrasted ACT UP’s position with that of Heritage of Pride, which, he noted, “wanted everything to be done in an orderly framework to show that homosexuals are good citizens.”⁶ For ACT UP, such respectability politics sanitized history and erased the urgency of AIDS.

Later that evening, hundreds gathered outside the Sixth Precinct—the site of the Stonewall raid and the 1970 Snake Pit incident, where broken windows and damaged police cars underscored the continuing role of the precinct as a symbol of state violence against queer life.⁷ These actions demonstrated ACT UP’s conviction that memory could not be confined to plaques or street signs. To remember Stonewall authentically meant to carry its radical energy forward, linking past rebellion with the ongoing catastrophe of AIDS.

By the early 1990s, however, the politics of memory itself was shifting. Though AIDS had become the leading cause of death for U.S. men aged 25 to 44, its visibility within national LGBTQ+ politics was already receding.⁸ At the 1993 March on Washington, journalist Jeffrey Schmalz noted with bitterness that “speaker after speaker ignored it.”⁹ From his hospital bed, Dr. Nicholas Rango of the New York State AIDS Institute lamented, “It’s like they are waiting for us to die so they can get on with their agenda.”¹⁰ By Stonewall 25 in 1994, Avram Finkelstein observed that AIDS had been “effectively locked out of hearts and minds.”¹¹ The commemorative focus shifted toward respectability politics, military service, and corporate sponsorship, even as deaths in New York surpassed 50,000.¹²

The renaming of Stonewall Place thus stands as a paradox: an official act of memorialization that coincided with a profound forgetting. For ACT UP, disrupting these ceremonies was not simply a protest, but a form of counter-memorial practice: a refusal to allow state-sanctioned memory to eclipse the epidemic’s ongoing devastation. Memorialization was not only a matter of stone and signage, but also of survival, visibility, and truth.

Footnotes

H. Eric Semler, “The Start of Gay Pride Weekend Is Marked With Demonstrations,” New York Times, June 25, 1989, https://www.nytimes.com/1989/06/25/nyregion/the-start-of-gay-pride-weekend-is-marked-with-demonstrations.html.

Gay Cable Network, Rally at Center/Stonewall Place, 1989, 18:09.070, LGBT Community Center National History Archive.

Ibid.

Semler, “The Start of Gay Pride Weekend.”

Semler, “The Start of Gay Pride Weekend.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

New York City AIDS Memorial, “HIV/AIDS Timeline,” accessed March 21, 2025, https://www.nycaidsmemorial.org/timeline.

Jeffrey Schmalz, “Whatever Happened to AIDS?” New York Times Magazine, November 28, 1993.

Ibid.

Avram Finkelstein, “Welcome to New York: Stonewall 25, 1994,” ACT UP New York, accessed May 3, 2025, https://actupny.org/documents/stonewallfly.html.

New York City AIDS Memorial, “HIV/AIDS Timeline.”

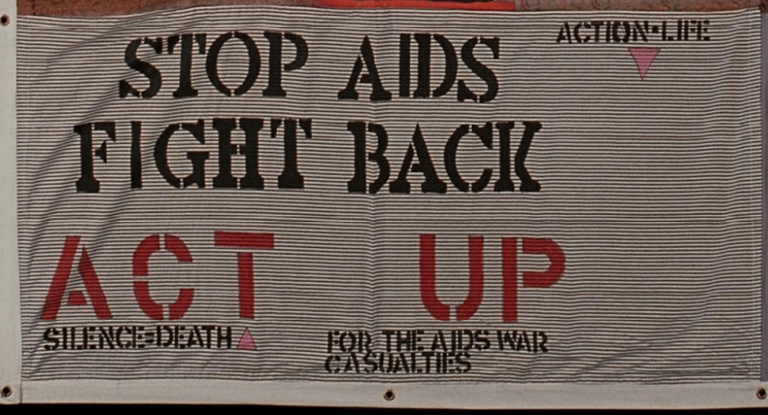

An ACT UP flyer from the 1994 “Spirit of Stonewall March” in New York City. Distributed publicly and wheatpasted to city surfaces, the flyer exemplified ACT UP and Gran Fury’s use of urgent design and guerrilla art tactics to mobilize AIDS activism. Source: STONEWALL Veterans' Association, “Spirit of Stonewall March,” accessed May 2, 2025, https://www.stonewallvets.org/SpiritofStonewall.htm.

ACT UP and the Spirit of Stonewall March, 1994

By the early 1990s, ACT UP had become synonymous with a new form of memorialization—one that refused to separate grief from defiance. Traditional candlelight vigils had offered solemn spaces for mourning, but ACT UP transformed these rituals into direct action. Funerals spilled into government buildings, die-ins shut down traffic, and chants of Silence = Death declared that remembrance without resistance was complicity. For ACT UP, memory was never passive. It had to be loud, disruptive, and impossible to ignore.

Avram Finkelstein, a member of ACT UP and one of the artists behind the Silence = Death poster, authored a tract disguised as an official program brochure and distributed it during the Stonewall 25 events. Its language was incendiary, reminding participants that Pride could not move forward without acknowledging the epidemic’s devastation:

"Remember, above all else, that you have just spent 10 days in the American epicenter of the AIDS epidemic. More than two hundred thousand have already died of AIDS—and it has barely been mentioned this week. 200,000 dead. That means 14,580 tons of bone and flesh; 630,000 pounds of brain matter; 197,000 gallons of blood, and 84,929,300 years of life that will never be lived. … AIDS is not a Cause or a Fundraiser or a Dance For Life. It is not a Chronic, Manageable Condition. It is not Angels, or Ribbons or T-shirts. It is not a Learning Experience. AIDS is a heaping pile of bodies, bodies of people. People we have loved, people we would have died for.… We have quite simply allowed it to become normal. Normal is fucked."¹

The tract disrupted the sanitized tone of the anniversary by confronting tourists and attendees with the stark reality of loss, denial, and the ongoing crisis. Finkelstein’s words underscored a central contradiction of Stonewall 25: the tension between global celebration and the unresolved grief of the epidemic.

ACT UP and the Quilt: Mourning or Militancy?

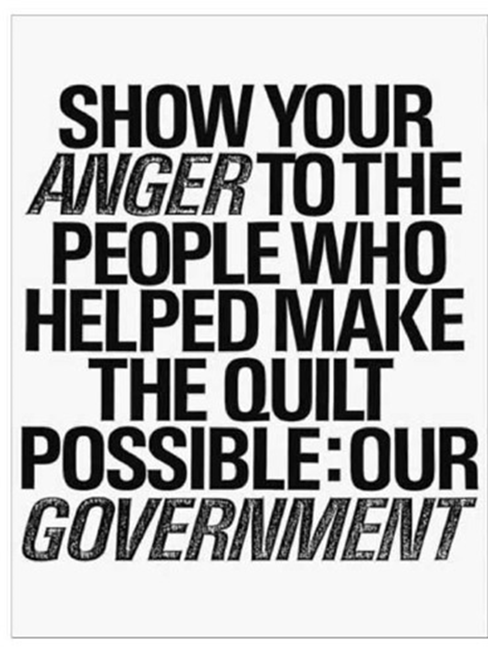

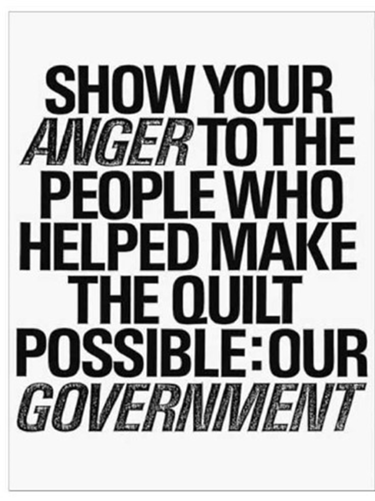

The AIDS Memorial Quilt brought grief into public space, transforming fabric into a powerful testament. When it spread across Central Park in June 1988, many saw it as a moving and necessary act of remembrance. Yet within New York’s activist community, especially among members of ACT UP, the Quilt raised difficult questions. Could mourning alone bring political change? Or did the beauty and quiet dignity of the panels risk softening the urgency of a crisis that demanded anger and confrontation?

ACT UP's political flyer, distributed during the Quilt’s display in Central Park, 1988—Boo-Hooray, "ACT UP Ephemera and Archives," accessed April 23, 2025, https://www.boo-hooray.com/advSearchResults.php?action=browse&category_id=222&orderBy=author&recordsLength=24&p=18.

ACT UP’s relationship to the Quilt was never one of outright rejection. Activists carried Quilt panels through the streets of Albany in 1988, folding grief into political protest. They also stood in candlelight vigils beside the Quilt on Christopher Street, finding strength in the blend of mourning and collective resolve. For some, this combination was transformative. Longtime member David Robinson later recalled being “bowled over” by the Quilt’s raw emotional power, describing it as a site where memory could move people to act.¹

At the same time, other activists warned against the dangers of symbolic mourning. In his 1988 “Why We Fight” speech, delivered at an ACT UP rally in Albany, Vito Russo insisted that “this is a war that has not united us, but divided us.”² His words underscored a deep tension: memorials could inspire solidarity, but they could also risk fragmenting a movement that demanded urgency and militancy.

Quilt panel created by ACT UP members calls for political engagement, harnessing grief into anger. 1988. National AIDS Memorial. Block # 1051 (02). “AIDS Memorial Quilt.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt.

This debate was echoed years later by filmmaker Jim Hubbard, who documented ACT UP from its earliest demonstrations. In a 2024 interview, Hubbard recalled that while the Quilt was “beautiful,” it also became “the acceptable sign of AIDS. The sort of thing George Bush could go down and talk in front of people … But it was pretty to look at.”³ For him, ACT UP’s more radical memorial practices—die-ins, political funerals, the scattering of ashes—refused that comfort. “From the tombstones … the cardboard tombstones and the die-ins which are symbolic, to … the desperation gets so great by 1992 or 1993 … that becomes more real. … First … just marching in [a dead friend’s] memory, but then they actually have the body.”⁴

As cultural critic Douglas Crimp later observed, ACT UP’s political funerals “refused to let the epidemic remain invisible.”⁵ Together, the Quilt and ACT UP embodied contrasting forms of AIDS memory: one consoling, the other confrontational. Their coexistence reveals how communities negotiated the politics of mourning in a city transformed by loss.

Notes

David Robinson, interview by Sarah Schulman, July 16, 2007, ACT UP Oral History Project, accessed February 24, 2025, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6075fe20d281ea3f320a7be9/t/60e7abb580504e0a7766c96b/1625795509476/082+-+David+Robinson.pdf.

Vito Russo, “Why We Fight,” ACT UP Historical Archive, March 1988, accessed April 23, 2025, https://actupny.org/documents/whfight.html.

Jim Hubbard, interviewed by Joseph Golden, December 2, 2024.

Ibid.

Douglas Crimp, Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS, Queer Politics, and the Ethics of Representation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 259–60.

From Symbol to Body: ACT UP and Political Funerals

In the late 1980s, mourning in New York’s AIDS crisis often took symbolic form. Activists staged die-ins on cathedral floors, lay down in streets with cardboard tombstones, and stitched names into the AIDS Memorial Quilt. These actions carried grief into public view, but they stood in for the dead — symbolic gestures that represented lives cut short.

By the early 1990s, symbolism was no longer enough. As filmmaker Jim Hubbard later observed, desperation drove a shift: “From the tombstones, the cardboard tombstones and the die-ins which are symbolic, to … the desperation gets so great by 1992 or 1993 … that becomes more real. First just marching in [a dead friend’s] memory, but then they actually have the body.”¹ ACT UP began to stage funerals not as quiet memorials, but as confrontations, using the bodies and ashes of loved ones to force the city, and the nation, to witness what government neglect had wrought.

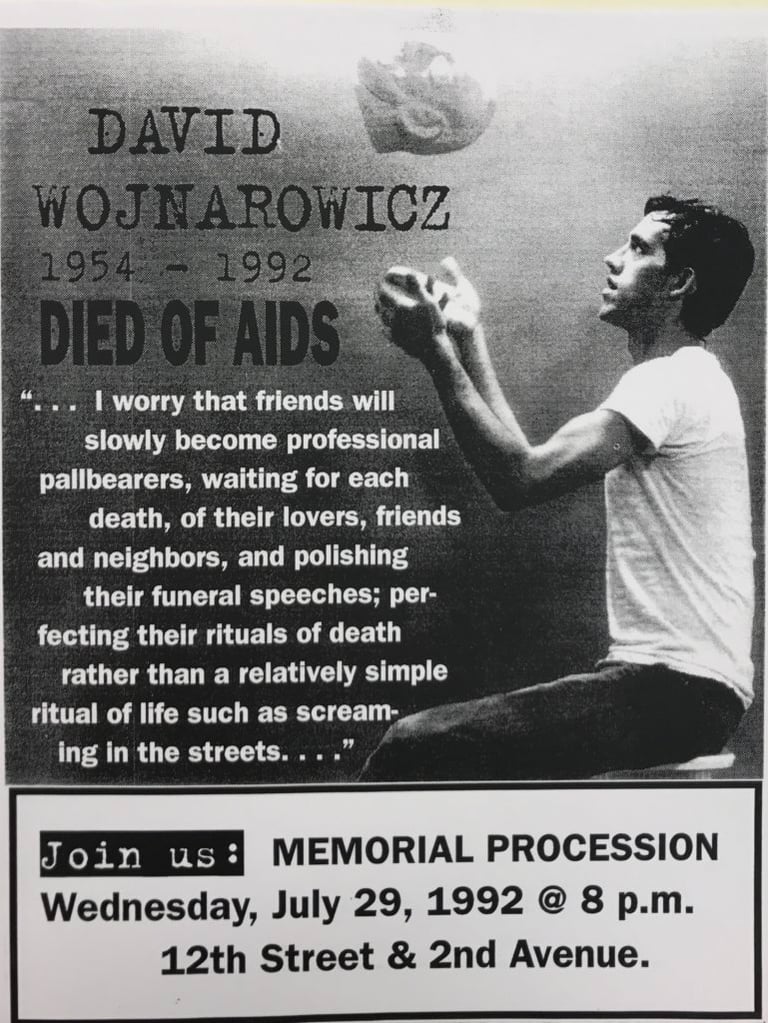

Flyer for David Wojnarowicz Funeral March, on July 29th, 1992.

"I worry that friends will slowly become professional pallbearers, waiting for each death, of their lovers, friends and neighbors, and polishing their funeral speeches; perfecting their rituals of death rather than simple rituals of life such as screaming in the streets..."

David Wojnarowicz: A Funeral as Confrontation

On September 14, 1992, what would have been David Wojnarowicz’s 38th birthday, hundreds of mourners gathered in the East Village to honor the artist, writer, and activist who had made AIDS visible through his art and words. Wojnarowicz had imagined funerals not hidden in private but staged before the nation as acts of defiance. In Close to the Knives, he wrote:

“I imagine what it would be like if, each time a lover, friend, or stranger died of this disease, their friends, lovers, or neighbors would take the dead body and drive with it in a car a hundred miles an hour to Washington, D.C., and blast through the gates of the White House and come to a screeching halt before the entrance and dump their lifeless form on the front steps.”¹

For a group of ACT UP activists known as the Marys, this vision felt not only possible but necessary. That summer, during the 1992 Pride Parade, they had circulated flyers asking for volunteers who would pledge to “leave your body to politics.” No one yet agreed, but the idea was planted: Wojnarowicz’s vision could be turned into a collective act.²

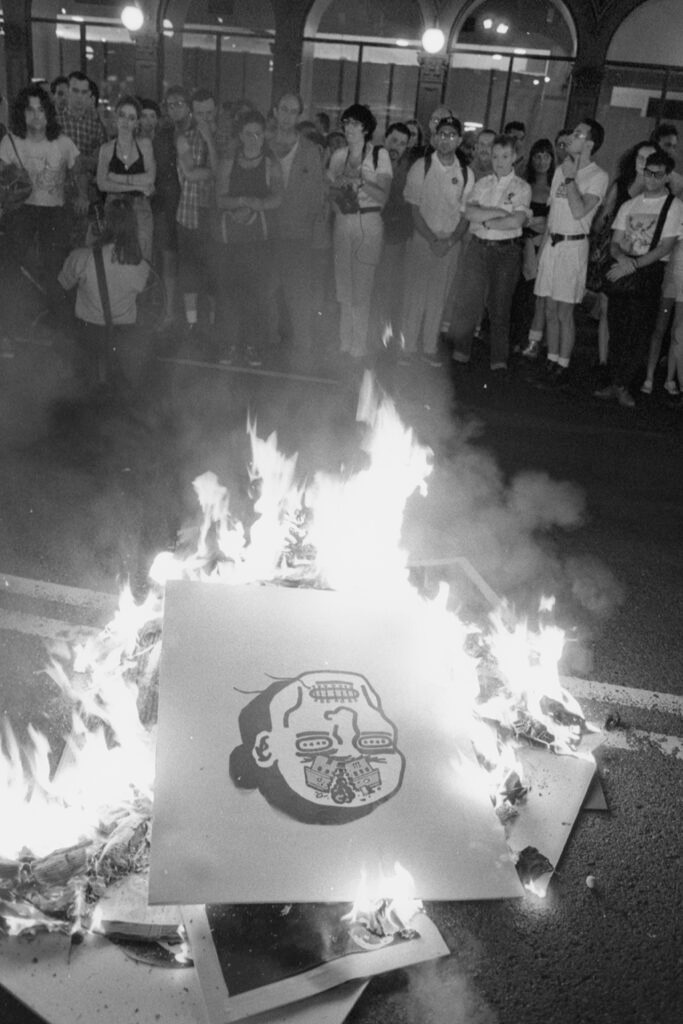

Memorial March for David Wojnarowicz, July 29, 1992. Photo by Brian Palmer. https://wojfound.org/scholarship/timeline/1992-political-funeral/

The Marys put this vision into practice at Wojnarowicz’s memorial. The march began outside his loft on Second Avenue and moved east to Avenue A. At its front, activists carried a banner that stretched across the street: “David Wojnarowicz, 1954–1992, Died of AIDS Due to Government Neglect.” Two women beat snare drums, others clapped sticks of wood, but the crowd walked in silence. Some held sunflowers, others carried reproductions of David’s artwork.³ As they moved south to Houston Street and north on the Bowery, people stepped off sidewalks to join. By the time they reached a parking lot across from Cooper Union, hundreds had gathered. There, activists projected Wojnarowicz’s name and the White House image with his words about delivering the dead to its gates. His essay was read aloud, closing with imagery of the White House steps. The message was unmistakable: grief itself could be a political weapon.⁴

The night ended in fire. Joy Episalla and Barbara Hughes dragged the banner into the street and set it ablaze. Friends hurled placards and sunflowers into the flames. As smoke rose over the East Village, mourners stood in silence, watching the banner’s words burn. Wojnarowicz’s funeral marked a turning point. Earlier that year’s Pride Parade had revealed activists’ hunger to transform mourning into militant action. By the fall, that impulse crystallized in Wojnarowicz’s own memorial: no longer symbolic tombstones or die-ins, but the public display of a body, a banner, and the defiance of flames. In death, as in life, David Wojnarowicz forced the world to see what it wished to ignore.

Notes

David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (New York: Vintage, 1991), 122.

Cynthia Carr, Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), 576.

Carr, Fire in the Belly, 576–77.

Carr, Fire in the Belly, 577.

ACT UP Memorial Flyer for Mark Lowe Fisher's Political Funeral, November 2, 1992.

Mark Lowe Fisher: “Bury Me Furiously”

On the night of November 2, 1992, the eve of Election Day, New York City witnessed one of the most defiant acts of mourning in its history. Mark Lowe Fisher, an ACT UP activist, architect, and member of the Marys affinity group, had died of AIDS just days before. Rather than accept a quiet service, Fisher left behind explicit instructions: his funeral should be a political act. In his statement Bury Me Furiously, he wrote:

“I want to show the reality of my death, to display my body in public. I want the public to bear witness. We are not just spiraling statistics; we are people who have lives, who have purpose, who have lovers, friends and families. And we are dying of a disease maintained by a degree of criminal neglect so enormous that it amounts to genocide. I want my own funeral to be fierce and defiant — to make the public statement that my death from AIDS is a form of political assassination. We are taking this action out of love and rage.”¹

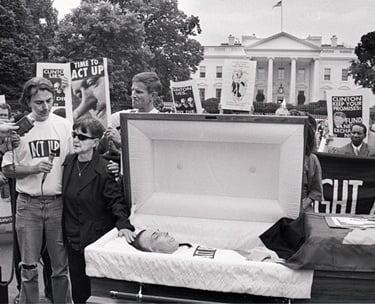

About 200 mourners carried out the wishes of Mark Lowe Fisher, 38, an architect and AIDS activist who died of AIDS, by taking his coffin to the Bush-Quayle campaign on West 41st St. In Manhattan. Photo by Bob Strong.

Fisher’s friends and comrades in ACT UP honored that wish. After a service at Judson Memorial Church on West 4th Street, his body was placed in an open casket and lifted onto the shoulders of mourners. The procession moved north up Sixth Avenue, stopping traffic as hundreds of activists walked nearly forty blocks to the Republican National Committee headquarters on West 43rd Street. There, on the eve of the election, they laid responsibility for his death at the feet of President George H. W. Bush, whose years of indifference had left nearly 200,000 Americans dead from AIDS.²

At the front of the march, demonstrators carried a stark banner: “MARK LOWE FISHER / 1953–1992 / DIED OF AIDS / MURDERED BY GEORGE BUSH.”³

This was not mourning in private. It was grief transformed into confrontation, a funeral as indictment. For Fisher, and for ACT UP, the act of carrying his body through the streets was a way of insisting that the dead not be hidden, that AIDS deaths were not natural or inevitable, but the direct result of government neglect. As historian Jennifer Brier has argued, political funerals like Fisher’s reframed the epidemic as a crisis of power, exposing the policies and prejudices that allowed the disease to spread unchecked.⁴

In that moment, the line between memorial and protest collapsed. The body itself became the message, making visible what the state preferred to ignore. Fisher’s funeral was both a final act of love by his community and a furious demand that his death, and the deaths of thousands of others, be reckoned with in public.

Notes

Mark Lowe Fisher, Bury Me Furiously, ACT UP Memorial Flyer, 1992, ClampArt Gallery, https://clampart.com/2011/01/act-up-memorial-flyer-judson-memorial-church.

Cynthia Carr, Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), 577.

ACT UP NY, “Mark Lowe Fisher Political Funeral,” DIVA TV, https://actupny.org/diva/polfunsyn.html.

Jennifer Brier, Infectious Ideas: U.S. Political Responses to the AIDS Crisis (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

On July 16, 1993, ACT UP carried Jon Greenberg’s body through the Lower East Side to Tompkins Square Park, transforming his funeral into a protest. Photograph by Thomas McGovern/Getty Images. https://theconversation.com/the-village-voices-photographers-captured-change-turmoil-unfolding-on-new-york-citys-streets-103820

Jon Greenberg: A Funeral of Wit and Fury

Jon Greenberg’s funeral was equal parts raw grief and dark, wry defiance. Friends carried his body in procession through the Lower East Side to Tompkins Square Park, turning a private loss into a public act of remembrance and community power. The march gathered neighbors and strangers as it moved, folding private sorrow into a visible claim on public space and insisting that the lives lost to AIDS be seen and named in the streets.¹

Greenberg was unmistakably irreverent about ritual and convention. He famously joked to friends, “I do not want an angry political funeral. I just want you to burn me in the street and eat my flesh,” a line he repeated with mordant humor at parties and even in crowded elevators. That macabre quip captured something essential about the funerals organized by ACT UP and allied affinity groups at the time: they mixed anger and theater, love and provocation, to shock the public into attention while honoring the dead on activists’ own terms.²

Jon Greenberg participated in the Day of Desperation Action at the PBS NewsHour Zap. He spoke at Mark Lowe Fisher's Political Funeral, and Barbara Hughes later read his speech at his own funeral:

"I am a person with AIDS.

I think about what's happened to my life since I was diagnosed over two years ago. I think about all the passion and precious time I've spent fighting this government's indifference toward me and all people with AIDS. And I realize that a lot of people out there -- gay, lesbian, and straight -- still do not believe that the AIDS crisis is a political crisis.

My friends and I have decided we don't want discreet memorial services. We understand our friends and families need to mourn. But we also understand that we are dying because of a government and a health care system that couldn't care less.

...I suspect -- I know -- my funeral will shock people when it happens. We Americans are terrified of death. Death takes place behind closed doors and is removed from reality, from the living. I want to show the reality of my death, to display my body in public; I want the public to bear witness. We are not just spiraling statistics; we are people who have lives, who have purpose, who have lovers, fiends, and families. And we are dying of a disease maintained by a degree of criminal neglect so enormous that it amounts to genocide.

I want my death to be as strong a statement as my life continues to be. I want my own funeral to be fierce and defiant, to make the public statement that my death from AIDS is a form of political assassination."²

Photographs and video from the day show a procession staged with careful theatricality. Activists and mourners carried banners and held the kinds of bold, photogenic visuals that ACT UP understood would travel through the press and into the public record. Photographer Tom McGovern later reflected that these demonstrations were staged to be seen and to change the story about AIDS, and his images of funerals like Greenberg’s document how activists choreographed grief into political testimony.³

Notes

¹ Funeral procession to Tompkins Square Park, July 16, 1993; see ACT UP NY, “Political Funerals,” DIVA TV / ACT UP archive.

² See ACT UP NY, “Political Funerals,” DIVA TV / ACT UP archive.

³ Tom McGovern interview and recollections on photographing ACT UP protests and funerals; see Tom McGovern, interview, The Conversation.

Political Funeral of Tim Bailey, Washington, DC, July 1, 1993. Footage shot by James Wentzy. (NYPL Tape # 01227-B) https://www.actuporalhistory.org/actions/political-funerals

Tim Bailey: A Funeral Blocked in Washington

Tim Bailey was a designer with Patricia Field and one of ACT UP’s most daring activists. He found his home in the Marys, an ACT UP affinity group infamous for bold actions—disrupting live broadcasts at CBS and PBS, crashing political events, and pushing protest into theatrical territory. Bailey brought that same flair to his own death.

At first, he wanted his body burned on a pyre in front of the White House as a final indictment of President Bill Clinton’s failed promises. Later, he revised his wishes: “Do something formal and aesthetic in front of the White House. I won’t be there anyway. It’ll be for you.”¹ On July 1, 1993, just months after Mark Fisher’s open-casket march through Manhattan, the Marys loaded Bailey’s body into a van and drove from New York to Washington, D.C. His family joined them, ready to honor his request for a public procession down Pennsylvania Avenue.

The plan was simple and devastating: carry Bailey’s coffin from the Capitol to the gates of the White House. But the state intervened. Capitol and Park Police surrounded the van and refused to allow the casket to be removed. What followed was a tense three-hour standoff. Activists argued that they were carrying out Bailey’s will. Police responded with force, roughing up mourners and arresting Bailey’s brother after a scuffle. Eventually, officers escorted the van out of the city, denying Bailey the final protest he had envisioned.²

The confrontation revealed the limits of public mourning when grief threatened political authority. Bailey’s funeral never reached the White House, but the sight of police blocking a coffin became its own indictment. For the Marys, it confirmed what they had long argued: AIDS was not only a medical crisis but a political one, sustained by government neglect and enforced by state power.

Bailey’s funeral demonstrated how far ACT UP had progressed from its early symbolic die-ins. The protesters who once used cardboard tombstones now carried real bodies. Even in defeat, the Marys transformed Bailey’s death into a public reckoning.

Notes

Tim Murphy, “How to Have Sex in an Epidemic,” New York Magazine, April 6, 2012, https://nymag.com/news/features/act-up-2012-4/#:~:text=after%20a%20three%2Dhour%20standoff.

“Political Funerals,” ACT UP Oral History Project, ACT UP New York, accessed September 23, 2025, https://www.actuporalhistory.org/actions/political-funerals.

Funeral procession for Aldyn McKean, across

14th Street to Union Square Park. March 4, 1994. https://actupny.org/diva/polfunsyn.html

Aldyn McKean’s Political Funeral

On March 4, 1994, ACT UP staged a political funeral for activist Aldyn McKean, who had died days earlier from AIDS-related complications. McKean was a sharp-tongued advocate, known for speaking truth to power at international AIDS conferences and demanding that scientists and policymakers listen to people living with HIV.¹

His funeral began at the Friends Meeting House on Rutherford Place, a historic Quaker gathering space in Manhattan. From there, hundreds of mourners carried his ashes west along 14th Street to Union Square, a site long associated with protest and dissent.² At the head of the procession, activists unfurled a banner with McKean’s image and the words: “A Great Hero in the Fight to End AIDS / Honor His Life—Take Action.”³

The march disrupted traffic as ACT UP members formed human chains across intersections, insisting that New Yorkers confront the epidemic’s toll. Union Square became the final stage of the funeral, linking McKean’s life and death to a tradition of labor struggles, antiwar rallies, and civil rights protests.

Later that year, ACT UP activists carried McKean’s ashes to the 10th International AIDS Conference in Yokohama, Japan, scattering them over the harbor.⁴ In death, as in life, McKean’s presence pressed activists and world leaders alike to act with urgency, turning mourning into a demand for justice.

Notes

“Aldyn McKean,” Wikipedia, last modified August 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aldyn_McKean.

“Political Funerals,” ACT UP New York Historical Archive, accessed September 23, 2025, https://actupny.org/actions/political-funerals.

ACT UP New York, memorial flyer for Aldyn McKean, March 4, 1994, reproduced in ACT UP Historical Archive.

“Political Funerals,” ACT UP New York Historical Archive.

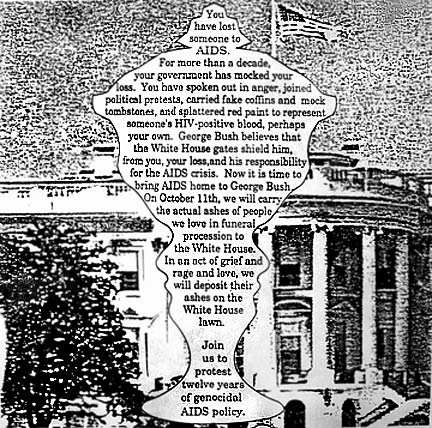

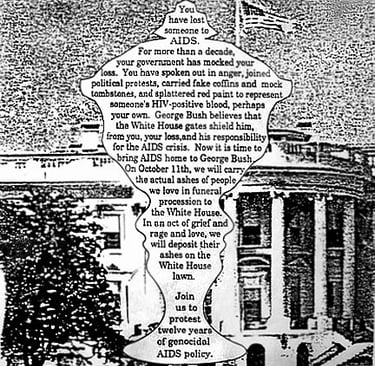

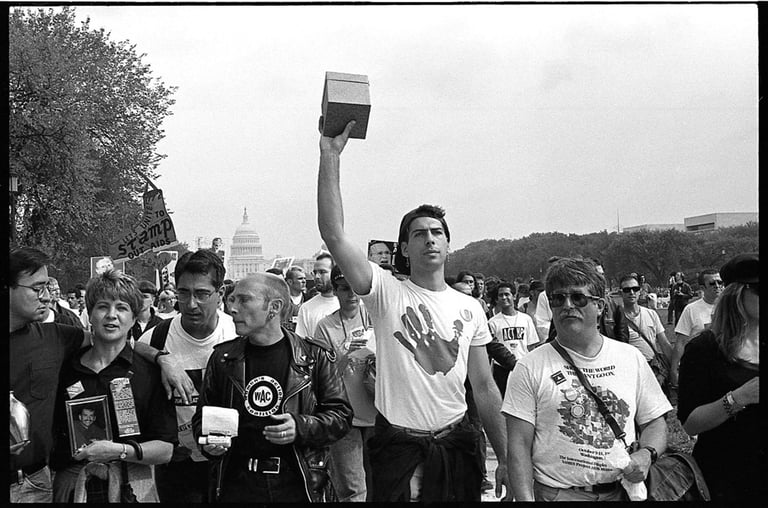

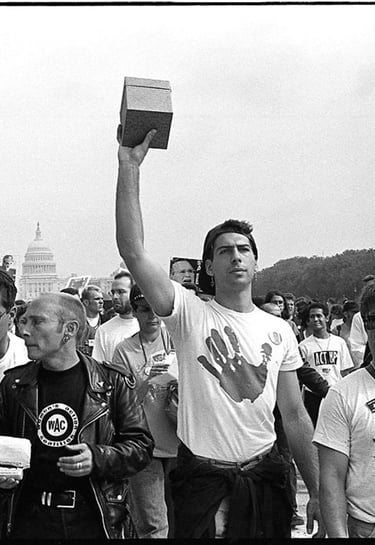

The Ashes Action: Mourning as Confrontation

By 1992, the escalating death toll—combined with continued government indifference—prompted a transformation in the language of protest. On October 11, ACT UP staged the Ashes Action at the gates of the White House, marking a radical redefinition of public mourning. Timed to coincide with the full display of the AIDS Memorial Quilt on the National Mall, the action offered a stark contrast. While the Quilt visualized absence, ACT UP brought presence. And while the Quilt was symbolic, this was literal. Protesters carried the cremated remains of their loved ones—partners, friends, fellow activists—and scattered them on the White House lawn.

You

have lost

someone to

AIDS.

For more than a decade,

your government has mocked your

loss. You have spoken out in anger, joined

political protests, carried fake coffins and mock

tombstones, and splattered red paint to represent

someone's HIV-positive blood, perhaps

your own. George Bush believes that

the White House gates shield him,

from you, your loss, and his responsibility

for the AIDS crisis. Now it is time to

bring AIDS home to George Bush.

On October 11th, we will carry

the actual ashes of people

we love in funeral

procession to

the White House.

In an act of grief and

rage and love, we

will deposit their

ashes on the

White House

lawn.

As ACT UP member Tim Robinson explained, “We weren’t going to do anything symbolic. The point was, these are the actual ashes. This is the literal physical result of the Bush administration’s AIDS policies.”¹ Fellow activist Avram Finkelstein recalled it as “the Quilt come to life—walking, shouting, and storming the White House... action is the real Quilt.”² The act collapsed the line between metaphor and reality: ashes were no longer standing in for the dead; they were the dead.

For David Robinson, who carried the ashes of his partner Warren, the action revealed the limits of symbolic mourning:

“George Bush would only be too happy for us simply to make beautiful panels—and I’m not belying (sic) the Quilt—it’s very useful, it’s very important, but it’s very beautiful and it does make a lot of people feel better... And I would wonder, is this making you feel like this is okay in some way? Because it’s not... From this point on, we are not going to hide this anymore, because hiding it is what they want.”³

David Robinson marched from the AIDS Quilt to the White House with cremated remains. October 11, 1992. Photo by Meg Handler, https://meghandlerphotography.com/gay-rights-act-up-aids-activism-nyc-1992-1994/

The Ashes Action was visceral, furious, and intimate. Chants and drumbeats accompanied the procession from the Quilt to the White House, where the lawn was transformed into a temporary cemetery (figure 67). Anthropologist Katherine Verdery has argued that dead bodies hold extraordinary symbolic power, provoking “awe, uncertainty, and fear associated with ‘cosmic’ concerns, such as the meaning of life and death.”⁴ In her words, “dead bodies animate the study of politics.”⁵ ACT UP’s deployment of corporeal remains was not only radical defiance but also a deliberate strategy of political inscription, using the dead themselves to write their presence into the national narrative.

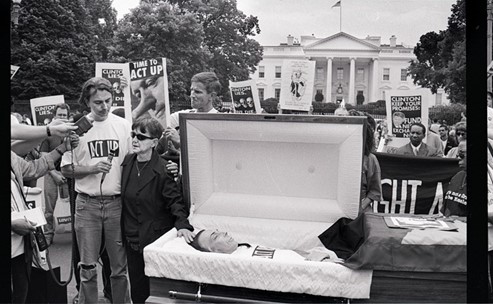

Steve Michael’s Political Funeral, June 4, 1998: "If I die, take my body to the White House. Show the world that Bill Clinton has lied to and betrayed people with AIDS," - Steve Michael. Photo by Bill Bytsura The AIDS Activist Project, Facebook page, accessed April 27, 2025, https://www.facebook.com/theaidsactivistproject/.

This form of militant mourning continued. On June 4, 1998, the political funeral of Steve Michael, founder of ACT UP/DC, carried his casket along Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House gates. “If I die, take my body to the White House,” Michael had instructed. “Show the world that Bill Clinton has lied to and betrayed people with AIDS.” His coffin was not scattered but displayed, demanding justice in death (figure 68). The evolution from ashes to the display of the body underscored the ways grief had become inseparable from confrontation.

As scholar Sarah Schulman later reflected, “The radical potential of queer mourning was not only to remember but to demand.”⁶ Building on José Esteban Muñoz’s insight that queer mourning works by disidentifying with dominant rituals of loss, ACT UP queered mourning itself. Their interventions transformed funerals, ashes, and coffins into political acts, refusing to let grief serve as quiet consolation. The Ashes Action was not a rejection of the Quilt but its transformation. The Quilt said, Look what we’ve lost. ACT UP asked, Who is responsible?

ACT UP and the Power of Memory

By the early 1990s, public mourning for AIDS had expanded into multiple and sometimes competing forms. Political funerals and the Ashes Action brought death itself into confrontation with political power.¹ In contrast, the New York Quilt Workshop and its Central Park display offered a quieter, hand-sewn form of remembrance that was no less radical; mourning transformed into care, intimacy, and visibility.² Vigils, too, carried grief into public space. Still, ACT UP retooled them: die-ins and moments of silence were deployed not as passive lament but as acts of theatrical disruption, where bodies on the street turned grief into accusation.³

Placed together, these practices reveal that AIDS memorialization in New York was never singular. The Quilt’s fabric, the vigil’s candles, Pride’s parades, and ACT UP’s banners all worked through different registers, but shared the same conviction: the dead must be remembered, and remembrance must be public. Pride became a stage where celebration and mourning intertwined, its moments of silence and banners of names amplified by ACT UP’s confrontational presence.⁴ Die-ins, chants, and even provocative floats reasserted the militant roots of Gay Liberation, making Pride not just a parade but a living memorial.⁵

In this light, the Central Park Quilt was not a soft alternative to ACT UP, nor were vigils a retreat from activism. Instead, each form—Quilt, vigil, parade, and protest—interlocked to create a patchwork of memory that balanced love and rage, consolation and confrontation. ACT UP sharpened the political edge of mourning, while the Quilt insisted on its intimacy; Pride held both in the streets, weaving grief into celebration.

Taken together, these practices show that AIDS memorialization was not about choosing between love and defiance, silence and spectacle. It was about holding them all at once. Sewing rooms, church steps, parade routes, and city streets became overlapping memorial landscapes, where mourning was never private but always political, and where survival itself became an act of resistance.

Footnotes

Tim Robinson, quoted in Jason Silverstein, “Why the Ashes of People With AIDS on the White House Lawn Matter,” VICE, August 29, 2016, https://www.vice.com/en/article/why-the-ashes-of-aids-victims-on-the-white-house-lawn-matter; Avram Finkelstein, quoted in Deborah B. Gould, Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s Fight Against AIDS (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), Kindle edition.

Cleve Jones, When We Rise: My Life in the Movement (New York: Hachette, 2016), Kindle edition, 219.

Deborah B. Gould, Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s Fight Against AIDS (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 171–72.

David W. Dunlap, “Thousands March in New York to Back Homosexual Rights,” New York Times, June 25, 1984, https://www.nytimes.com/1984/06/25/nyregion/thousands-hold-march-to-back-homosexuals.html; Tim Murphy, “A Timeline of HIV/AIDS Representation at New York City’s Pride March, From the Early 1980s to Modern Times,” The Body, July 1, 2024, https://www.thebody.com/article/timeline-hiv-representation-nyc-pride-march.

Avram Finkelstein, quoted in Gilbert Baker and Cindy Black, Rainbow Warrior: My Life in Color (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2019), 207.

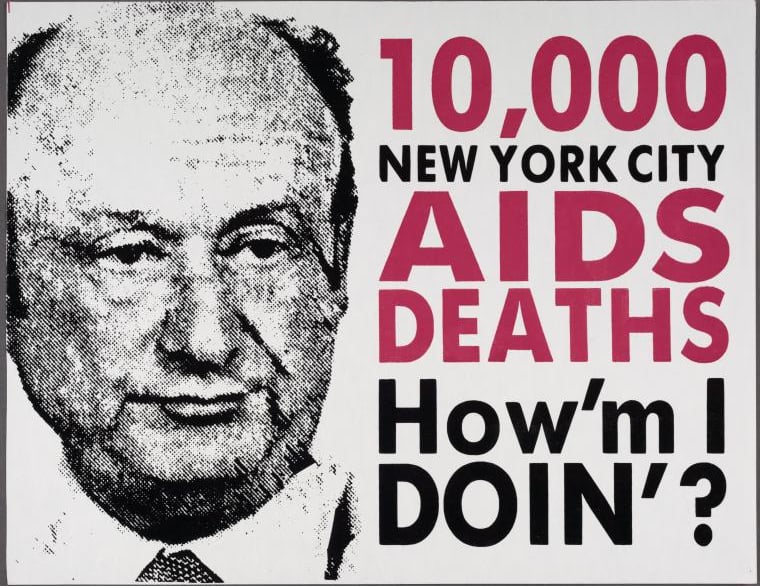

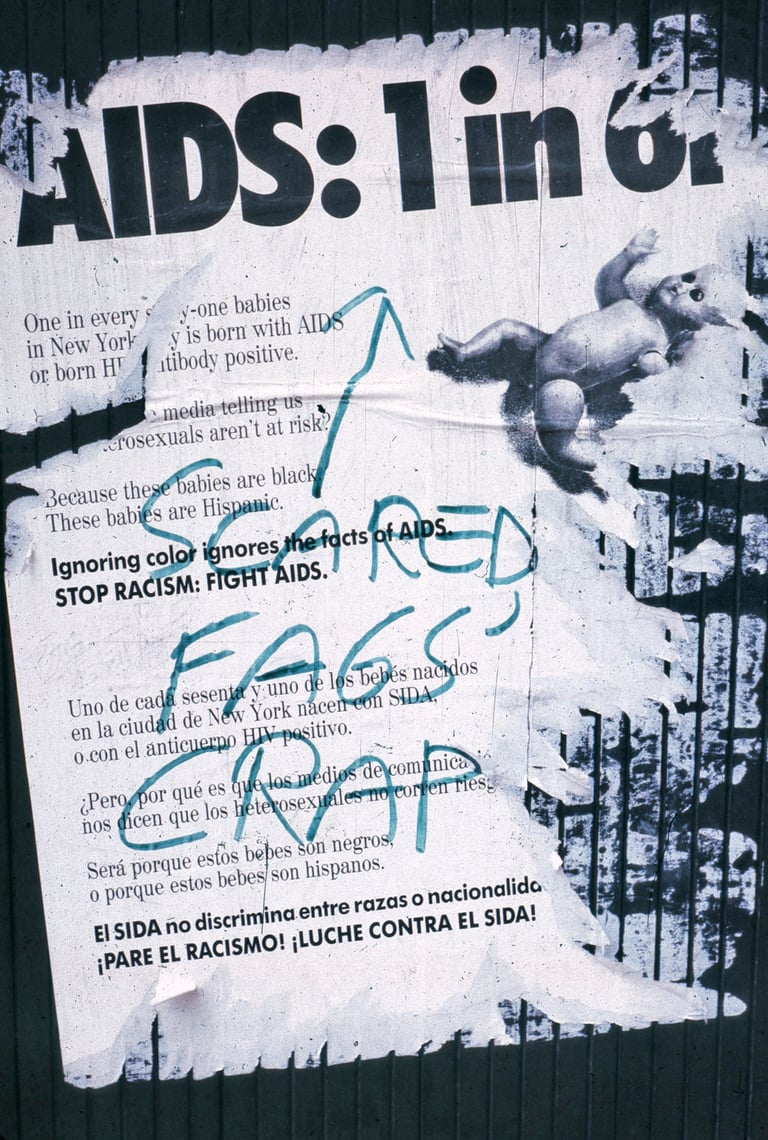

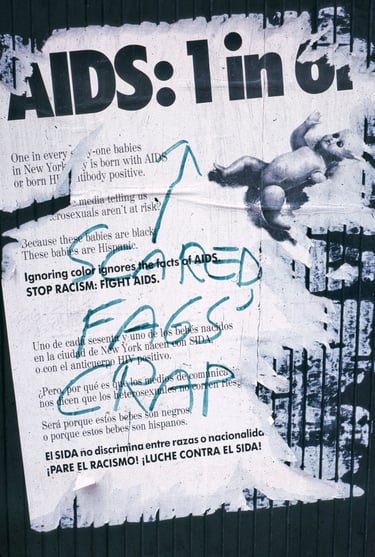

Gran Fury, AIDS: 1 in 61, 1989

Formed out of ACT UP, the artist collective Gran Fury used striking visual messages to turn activism into public education. Their 1 in 61 poster revealed that one in sixty-one babies born in New York City carried HIV antibodies, widening the story of AIDS to include women, children, and communities of color. When defaced with the words “scared fags crap,” the poster became more than an artwork—it became an artifact of its time, exposing the hostility activists faced while fighting for visibility. Today, it stands as a record of how art and advocacy merged in the struggle for life and remembrance.

Source: Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/8af4d010-8181-0137-6d53-3995b828f3fc?canvasIndex=0

Share Your Story

Your voice matters. If you have memories, photographs, or reflections connected to the AIDS crisis in New York City, we invite you to share them. Together we can preserve these histories and ensure they are never forgotten.