Origins of the Crisis: AIDS in New York City

From the wards of St. Vincent’s Hospital to the grassroots work of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and the militant activism of ACT UP, New Yorkers built their own networks of care and remembrance.

Joseph Golden

9/8/20257 min read

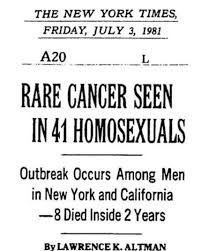

On July 3, 1981, The New York Times announced “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” The headline was misleading—patients were young, otherwise healthy, and not all gay. Reporter Lawrence Altman later called these notices “the first official harbingers of AIDS.”

From the wards of St. Vincent’s Hospital to the grassroots work of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and the militant activism of ACT UP, New Yorkers built their own networks of care and remembrance. These early struggles and losses set the stage for the memorial traditions that would transform grief into visibility and resistance.

The First Reports

On July 3, 1981, The New York Times carried a story that most readers likely overlooked. Buried deep inside the paper on page A20, its headline read: “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” The article, clinical in tone, reported that doctors in New York and California had identified a strange new illness striking young gay men.¹ For those who saw it, the meaning was ominous. What seemed at first a medical curiosity would soon grow into a devastating epidemic, one that would change New York City forever.

Within months, hospitals were filling with patients suffering from unusual infections like Kaposi’s sarcoma and Pneumocystis pneumonia. Doctors did not know what caused the disease or how it spread, and there were no treatments to offer. By the end of 1983, more than 850 New Yorkers had died.² St. Vincent’s Hospital in Greenwich Village, blocks from Christopher Street, quickly became the center of the city’s medical response. Its AIDS ward overflowed with patients, many abandoned by their families and left to die in isolation.³ The ward became both a place of compassion and a stark symbol of society’s failure to confront the epidemic.

Government Neglect and Public Fear

City Hall, led by Mayor Edward I. Koch, offered little support. Despite mounting deaths, his administration allocated just $24,500 to AIDS programs in the first two years.⁴ Activists accused Koch of deliberate neglect, and his silence on the crisis became, in the words of journalist David France, “his greatest failure.”⁵ At the federal level, President Ronald Reagan did not publicly utter the word “AIDS” until 1987.

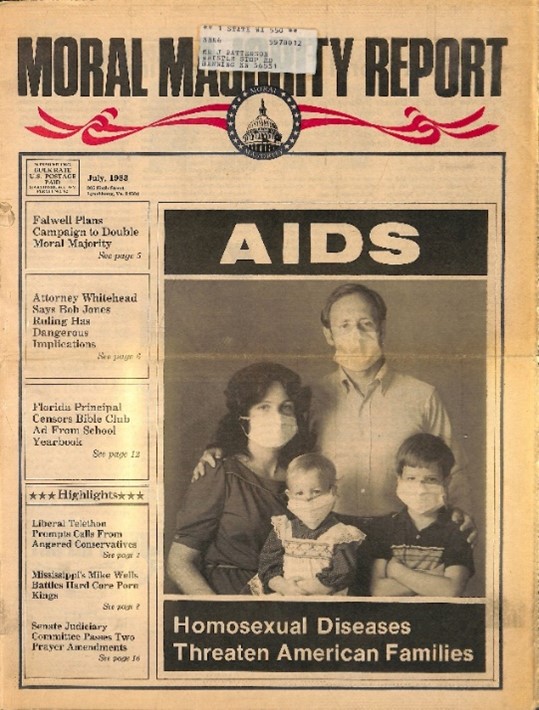

Fear and misinformation spread almost as fast as the virus. Without a reliable test until 1986, many believed AIDS could be contracted through casual contact—sharing a glass, a sneeze, or even a handshake. Hospitals sometimes refused to treat patients. Schools barred children who had contracted HIV through blood transfusions. A 1985 Los Angeles Times poll showed that half of Americans supported quarantining people with AIDS, while some even endorsed tattoos or identification cards.⁶,⁷ People with AIDS lost their jobs, were evicted from their homes, and were denied basic medical care. Entire communities, including gay men, Haitians, and intravenous drug users, were stigmatized and scapegoated, branded as dangerous rather than recognized as victims of a public health crisis.

The Moral Majority cast AIDS as divine punishment for “immoral” lifestyles, especially homosexuality, and pushed for a return to traditional values rather than medical solutions. Their stance of judgment and blame stood in stark contrast to public health efforts and community care.

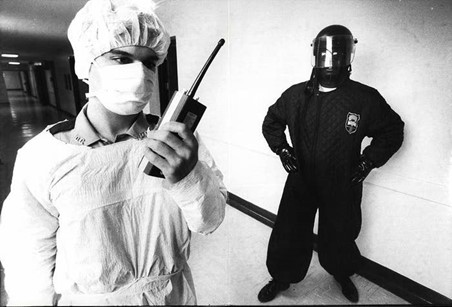

Westchester County correctional officers in New York in charge of inmates in the hospital ward wear special garb due to the uncertainty of AIDS. 1983. New York Post Archives

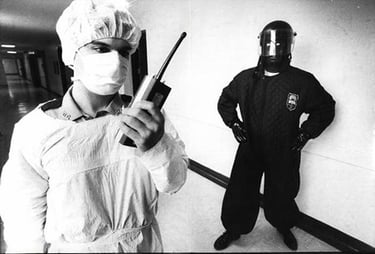

The headquarters of Gay Men’s Health Crisis in Chelsea in 1983. The group was the nation’s first dedicated to the prevention of H.I.V./AIDS, and the care and advocacy for those infected. Don Hogan Charles/The New York Times

Disenfranchised Grief and the Birth of Activism

The grief was crushing, and it was often invisible. Families sometimes refused to claim the bodies of loved ones. Funerals were small, hidden, or avoided altogether, cutting partners and friends out of the mourning process. This absence of public recognition created what scholars call disenfranchised grief—loss that society refuses to acknowledge.⁸ Yet from this silence, new rituals of remembrance emerged. Candlelight vigils moved down Christopher Street, transforming the heart of queer New York into a corridor of mourning. Names of the dead were read aloud at Pride marches. In 1988, the AIDS Memorial Quilt stretched across Central Park’s Great Lawn, a vast patchwork of lives lost, stitched together in defiance of erasure.

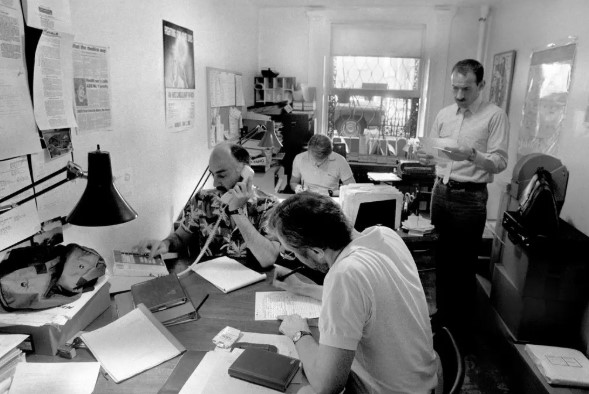

At the same time, networks of care and activism arose from within the community itself. Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), founded in 1982, became a lifeline for thousands, offering counseling, home visits, and legal aid when no government services existed. Volunteers cooked meals, held hands, and provided dignity in the face of abandonment. By 1987, grief and outrage fueled the birth of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), whose militant street protests, die-ins, and political funerals forced the epidemic into public view and pressured leaders to act. In the absence of compassion from leaders, it was neighbors, lovers, and activists who created the infrastructures of care and the politics of resistance.

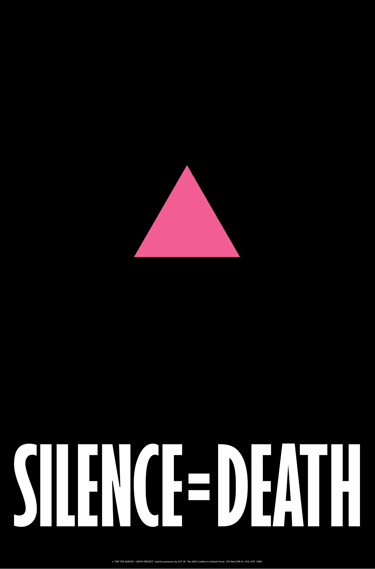

The 1986 Silence=Death poster from the AIDS crisis (designed by the Silence=Death Project, formed in 1985), illustrating the use of an inverted version of the pink triangle from the Holocaust.

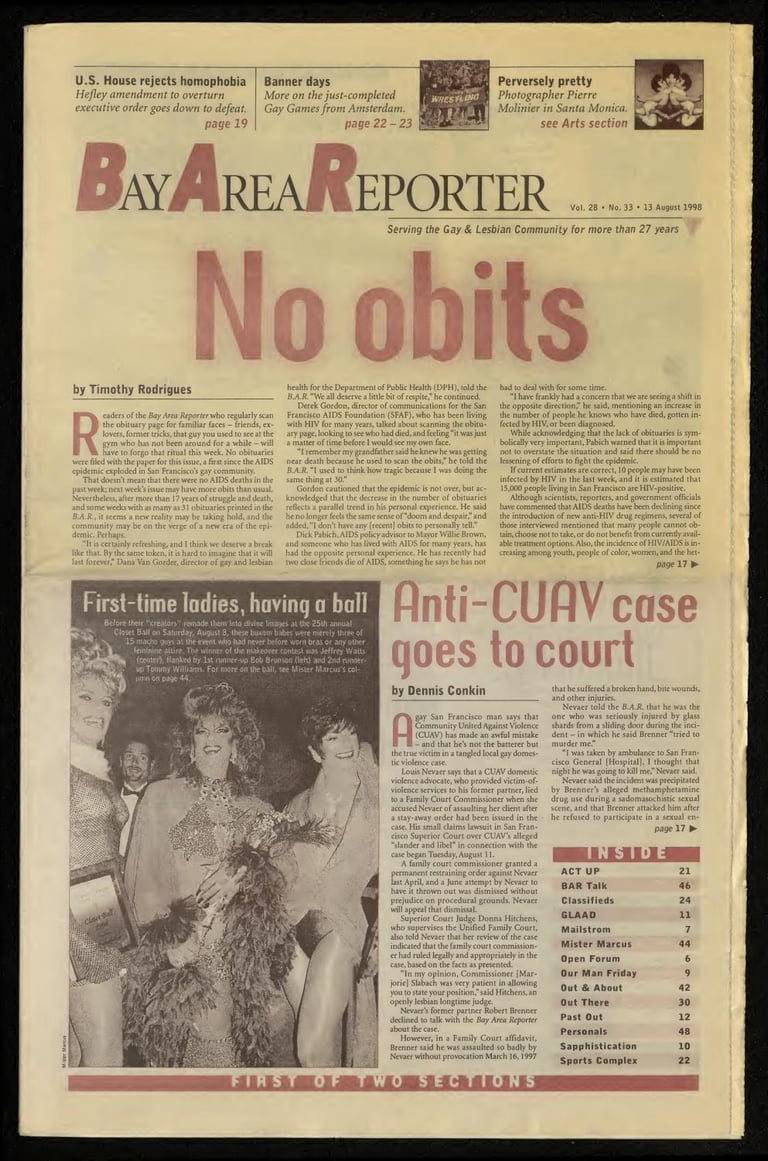

An impactful headline from the August 13, 1998, issue of the Bay Area Reporter, a San Francisco LGBTQ+ weekly, declares, "No obits." This marked the first time in 17 years that the newspaper did not contain any AIDS-related obituaries, signaling a powerful but provisional turning point in the epidemic following the introduction of new antiretroviral drugs.

While the headline brought a wave of hope, the accompanying article and public health officials cautioned that it was not the end of the crisis, as the pandemic continued globally and access to treatment remained a challenge.

From Crisis to Memory: The 1990s and the Politics of Forgetting

By the mid-1990s, scientific breakthroughs began to change the landscape of the epidemic. In 1996, researchers introduced a new class of medications known as protease inhibitors—part of the first effective combination therapy, soon called “the cocktail.” The results were staggering: for many who could access treatment, AIDS transformed from a death sentence into a chronic, manageable condition.⁹ Hospital wards that had once overflowed with patients began to empty. Deaths declined sharply for the first time in fifteen years.

Yet with survival came a new kind of loss—what journalist Jeffrey Schmalz called “AIDS amnesia.”¹⁰ As the crisis seemed to recede, public attention shifted. Media coverage waned, funding for AIDS services decreased, and many survivors found themselves isolated in a culture eager to move on. For long-term survivors, the trauma of survival collided with the invisibility of recovery. Historian Douglas Crimp, reflecting on this period, warned that the rush to declare the epidemic “over” risked erasing the radical politics of care and activism that had defined the struggle.¹¹

In New York, the 1990s were a paradox: a decade of relief and exhaustion, of mourning and forgetting. New medications extended life, but only for those with access and privilege. The poor, the uninsured, people of color, and women—many of whom had been left out of earlier activism—continued to die at alarming rates.¹² Meanwhile, memorials like the Quilt, political funerals, and vigils gave way to new conversations about how to commemorate a crisis that no longer dominated headlines but remained far from over.

As cultural historian Marita Sturken has argued, the memorial practices that emerged during the AIDS crisis blurred the line between mourning and activism, between public ritual and private loss.¹³ The tension between remembrance and forgetting—between visibility and disappearance—continues to shape how we understand the epidemic today.

Conclusion: Memory as Defiance

New York City, the epicenter of the epidemic, became both a site of devastating loss and of extraordinary resilience. The early years of the AIDS crisis revealed not only the cruelty of indifference but also the strength of community. From the bedside volunteers at St. Vincent’s to the protesters filling Wall Street and City Hall, people transformed private sorrow into public defiance.

This transformation, in which mourning gave way to militancy, as Douglas Crimp famously wrote, laid the foundation for a culture of remembrance that continues to this day.¹⁴ The vigils, marches, and quilts were not only acts of grief but of historical preservation, documenting lives that official archives ignored. In many ways, these were the first community archives of the epidemic, grassroots repositories that refused to let queer history fade into oblivion.

To remember the origins of the crisis is to remember the power of those who refused to disappear. Their legacy endures in every memorial, archive, and story that insists AIDS history belongs not only to medicine but to art, activism, and the ongoing work of justice.

Notes

Lawrence K. Altman, “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” The New York Times, July 3, 1981.

Randy Shilts, And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987), 300–302.

David France, How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), 47–49.

Sarah Schulman, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), 15.

France, How to Survive a Plague, 52.

“Half of Americans Favor AIDS Quarantine,” Los Angeles Times, August 16, 1985.

Dennis Altman, AIDS in the Mind of America (Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1986), 88–90.

Kenneth J. Doka, Disenfranchised Grief: Recognizing Hidden Sorrow (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1989).

Steven Epstein, Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 327–33.

Jeffrey Schmalz, “Whatever Happened to AIDS?” The New York Times Magazine, November 28, 1993.

Douglas Crimp, “Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics* (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 13–15.

Gregg Gonsalves and Peter Staley, “Panic, Paranoia, and Public Health,” The American Journal of Public Health 104, no. 1 (January 2014): 18–20.

Marita Sturken, Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 168–70.

Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” in AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism, ed. Douglas Crimp (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1988), 3–18.